Please set your exam date

Nursing care during a pediatric emergency

Study Questions

Practice Exercise 1

A 3-year-old is brought to the emergency department with a history of choking. The child is alert, crying loudly, and has a strong cough. What is the most appropriate nursing intervention?

Explanation

Airway obstruction in children is a life-threatening emergency. Management depends on whether the obstruction is partial or complete. Children who can cry and cough effectively usually have a partial obstruction, and the safest action is to allow them to clear their airway naturally while being closely observed.

Rationale for correct answer:

3. When a child is alert and able to cough forcefully, cry, or speak, it means the airway is only partially obstructed. The safest action is to allow the child to continue coughing, because this is the body’s most effective way to expel the foreign object. Intervening too early like with back blows, abdominal thrusts, or CPR can worsen the obstruction. Continuous monitoring is essential to detect if the obstruction worsens.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Performing the Heimlich maneuver (abdominal thrusts) is indicated only if the child is unable to cough, speak, or breathe signifying complete obstruction.

2. Immediately beginning CPR is indicated if the infant becomes unresponsive and pulseless, not while alert and crying.

4. Performing a blind finger sweep is never performed, as it can push the object further down the airway and worsen the obstruction.

Take home points

- Partial obstruction indicated by effective cough/cry the nurse should encourage coughing, monitor closely.

- Complete obstruction indicated by the child being silent, cyanotic, unable to cry/cough, the nurse should perform the Heimlich maneuver in a child.

- For an unresponsive infant, begin CPR and check airway before rescue breaths.

- Never perform blind finger sweeps in infants or children.

When performing CPR on a 7-year-old child, what is the correct compression-to-breath ratio for a single rescuer?

Explanation

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in children follows specific guidelines that differ based on age and whether one or two rescuers are present. Proper compression-to-breath ratios are critical to maintain effective circulation and oxygenation.

Rationale for correct answer:

1. According to the American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines, when there is only one rescuer, the compression-to-breath ratio is 30:2 for infants, children, and adults. This standardization ensures simplicity during emergencies, minimizing confusion and maximizing effectiveness.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

2. 15:2: This ratio applies when two rescuers are performing CPR on infants or children, not a single rescuer.

3. 5:1: This is an outdated guideline, no longer recommended in pediatric CPR.

4. 10:1: This is not part of current CPR recommendations.

Take home points

- Single rescuer (infant, child, adult): 30:2 compression-to-breath ratio.

- Two rescuers (infant/child): 15:2 compression-to-breath ratio.

- High-quality CPR: compressions at 100–120/min, depth about 2 inches (5 cm) in children, allowing full chest recoil.

- Early activation of emergency response and timely defibrillation (if indicated) are vital for survival.

A 4-year-old child is found unresponsive and without a pulse. You are a single rescuer. After calling for help, what is your next immediate action?

Explanation

In pediatric emergencies, when a child is found unresponsive and pulseless, the priority is to initiate high-quality chest compressions immediately. Early chest compressions help maintain circulation to vital organs until advanced help arrives. Rescue breaths and other airway maneuvers are important, but they come after establishing circulation through compressions.

Rationale for correct answer:

3. The AHA pediatric CPR guidelines state that if a child is pulseless and unresponsive, the rescuer should immediately begin chest compressions. Compressions should be performed at a rate of 100–120 per minute, depth of about 2 inches (5 cm), with full chest recoil. This prioritizes circulation, buying time until advanced airway and breathing support can be established.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Rescue breaths are given after 30 compressions when performing CPR alone. Starting with breaths instead of compressions delays critical circulation.

2. Checking for a foreign object in the mouth through a finger sweep is not recommended unless you can see an obstruction. Wasting time searching delays CPR.

4. Performing the Heimlich maneuver is used for choking with foreign body airway obstruction, not for an unresponsive, pulseless child.

Take home points

- For unresponsive and a pulseless child you should start compressions immediately.

- Single rescuer CPR ratio (child): 30:2 (compressions to breaths).

- Compression rate: 100–120/min, depth about 5 cm (2 inches).

- Avoid blind finger sweeps; only remove visible obstructions.

- Heimlich maneuver is for responsive choking, not pulseless/unresponsive cases.

Which of the following is a critical difference between a child's respiratory system and an adult's?

Explanation

Children’s respiratory systems differ significantly from adults’, which makes them more vulnerable to airway compromise and respiratory distress. Understanding these anatomical and physiological differences is essential for effective pediatric assessment and emergency care.

Rationale for Correct answer:

4. Children’s airways are smaller in diameter and more flexible, which increases their risk of obstruction from mucus, edema, or external pressure. Their softer cartilage makes the airway more prone to collapse, particularly during respiratory distress or improper head positioning. Even a small reduction in airway diameter such as a 1 mm swelling greatly increases airway resistance in children compared to adults (Poiseuille’s law).

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Children have smaller lung volumes, which limits oxygen reserves and contributes to quicker desaturation.

2. Children actually have a larger tongue relative to the airway, which increases the risk of obstruction.

3. The trachea in children is shorter and more flexible, contributing to airway instability and higher risk of right mainstem intubation.

Take home points

- Children’s airways are narrower and softer, making them more prone to obstruction and collapse.

- Larger tongue relative to mouth size also increases obstruction risk.

- Shorter trachea raises the risk of endotracheal tube displacement or malposition.

- Pediatric patients desaturate faster due to smaller lung volumes and higher metabolic demands.

You are a nurse performing two-rescuer CPR on a 10-month-old infant. What is the correct compression-to-breath ratio and technique?

Explanation

Infant CPR requires knowledge of both the appropriate compression-to-breath ratio and the technique based on the number of rescuers. For infants younger than 1 year, two-rescuer CPR follows a different ratio than single-rescuer CPR, and the recommended compression technique provides better depth and consistency.

Rationale for correct answer:

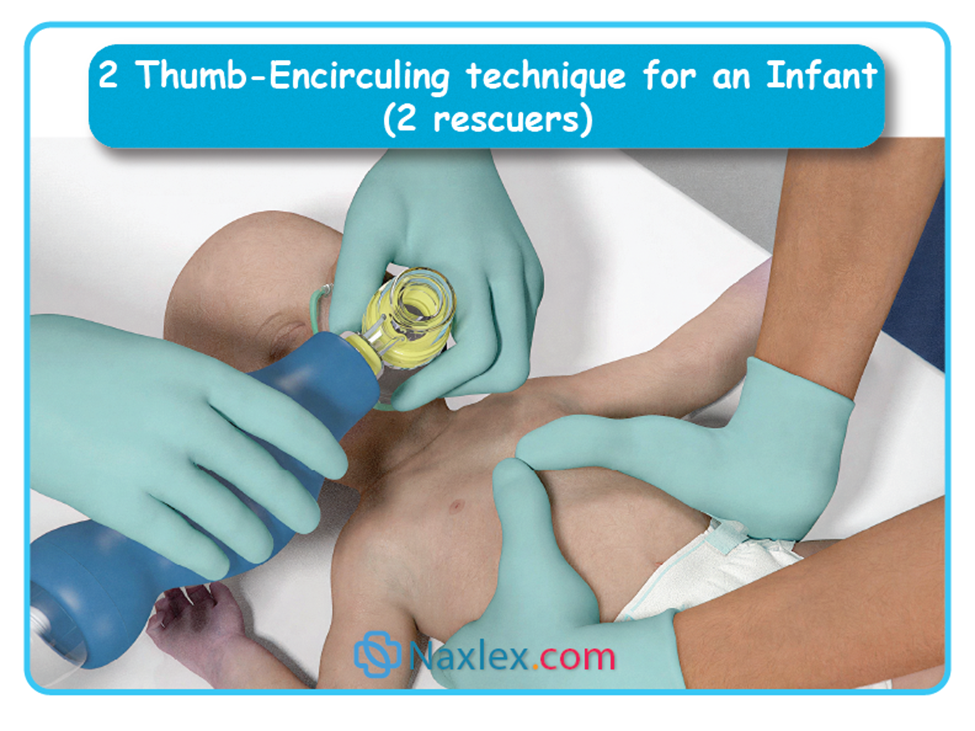

2. In two-rescuer infant CPR, the correct compression-to-breath ratio is 15:2. The two-thumb encircling hands technique is preferred because it produces deeper, more consistent compressions, allows for better chest recoil, and improves coronary perfusion compared to the two-finger method. This method also enables the rescuers to maintain good control of the airway and chest simultaneously.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. 30:2, using two fingers: This ratio is correct only for a single rescuer, not two. The two-finger method is acceptable for single-rescuer CPR when encircling is not feasible.

3. 30:2, using the heel of one hand: This technique is used for children (1 year to puberty), not infants. Infants require two fingers or two thumbs.

4. 15:2, using two fingers: While the ratio is correct for two rescuers, the technique is not ideal. The two-finger method is less effective than the two-thumb encircling technique in generating adequate compressions.

Take home points

- Single rescuer infant CPR: 30:2 ratio, two-finger technique.

- Two-rescuer infant CPR: 15:2 ratio, two-thumb encircling technique (preferred).

- Compression depth: about 1.5 inches (4 cm) at a rate of 100–120/min, allowing full chest recoil.

- Airway and breathing support remain critical; CPR in infants often stems from respiratory failure leading to cardiac arrest.

Practice Exercise 2

A 3-year-old is seen in the clinic at 8:30 pm with a history of vomiting for 2 days and poor oral intake; he has voided once since the previous day. Examination reveals a lethargic child sitting on the mother’s lap. He has a capillary refill of 4 seconds, apical heart rate 128, respiratory rate of 32, and poor skin turgor. State body weight is 25 kg. Based on this information, the nurse anticipates performing which of the following?

Explanation

Severe dehydration in children can occur quickly due to vomiting, diarrhea, or poor oral intake. Clinical indicators include lethargy, delayed capillary refill, tachycardia, poor skin turgor, and oliguria. In such cases, oral rehydration is insufficient, and rapid IV isotonic fluid resuscitation is required to restore intravascular volume and prevent hypovolemic shock.

Rationale for correct answer:

3. The child shows signs of severe dehydration with hypovolemic shock (tachycardia, delayed cap refill, lethargy, poor urine output). The correct intervention is an IV bolus of isotonic crystalloid (0.9% NS or LR), 20 mL/kg, over ~20 minutes. For a 25-kg child: 20 mL/kg × 25 = 500 mL NS. This restores intravascular volume rapidly and prevents progression to shock.

Rationale for Incorrect Answers

1. Oral rehydration (Pedialyte) is appropriate for mild/moderate dehydration, but this child is too lethargic and hemodynamically unstable for oral intake.

2. 5% Dextrose in water (D5W) is a hypotonic solution; not used for bolus resuscitation. Risk of cerebral edema and hyponatremia.

4. 1000 mL D5 0.45% NS is too large a volume for bolus in a 25-kg child and contains dextrose + hypotonic fluid, which is unsafe for initial resuscitation.

Take home points

- First-line fluid for pediatric dehydration/shock: isotonic crystalloid (NS or LR).

- Bolus dose: 20 mL/kg IV over 20 minutes (repeat as needed).

- Avoid dextrose-containing or hypotonic fluids for bolus therapy.

- Switch to oral rehydration once the child is stable and alert.

A 6-year-old is brought to the ED after a bicycle accident. You notice cool, pale extremities, a prolonged capillary refill of 4 seconds, and a weak, thready peripheral pulse. His blood pressure is within normal limits for his age. What stage of shock is he most likely in?

Explanation

Shock in children progresses through stages, but unlike adults, blood pressure remains normal until late because of strong compensatory mechanisms (tachycardia and vasoconstriction). Early recognition relies on perfusion signs such as skin changes, delayed capillary refill, and weak pulses. Identifying compensated shock is critical, as intervention at this stage can prevent deterioration.

Rationale for correct answer:

3. Compensated shock refers to impaired perfusion with normal blood pressure. Findings include: cool, pale extremities, delayed capillary refill (>3 seconds), weak/thready peripheral pulses, tachycardia. The body is maintaining perfusion to vital organs through vasoconstriction, but early warning signs are present. This child’s normal BP + poor perfusion signs indicates compensated shock.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Decompensated shock occurs when compensatory mechanisms fail resulting in hypotension. Since BP is still normal here, this is not decompensated shock.

2. Irreversible shock is the final stage with profound acidosis, cellular injury, organ failure, and death, not consistent with this presentation.

4. Cardiogenic shock is caused by pump failure such as congenital heart disease and myocarditis. It would present with signs of poor perfusion plus pulmonary congestion or hepatomegaly, not seen here.

Take home points

- Compensated shock in children: normal BP, but poor perfusion signs (cool extremities, prolonged cap refill, weak pulses, tachycardia).

- Decompensated shock: hypotension appears late and is dangerous in children.

- Bradycardia and hypotension are very late/preterminal signs.

- Early recognition and aggressive intervention (oxygen, fluids, monitoring) can prevent progression.

A nurse is caring for a 3½-year-old child who consumed a bottle of aspirin 10 minutes earlier.

Which of the following findings would the nurse expect to see?

Explanation

Aspirin (salicylate) poisoning is a common pediatric emergency that affects both the metabolic system and the respiratory center. This causes respiratory alkalosis, followed later by metabolic acidosis as toxicity progresses. Early recognition of breathing changes is critical in identifying aspirin toxicity.

Rationale for correct answer:

2. Hyperpnea: Salicylates stimulate the medullary respiratory center, leading to rapid, deep breathing. This results in respiratory alkalosis in the early phase of poisoning.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Hyperglycemia: Aspirin poisoning is more often associated with hypoglycemia due to increased metabolic demand.

3. Hyperthermia: Can occur in severe toxicity due to increased metabolic activity, but it is not an early or expected initial finding.

4. Hypernatremia: Salicylate poisoning is not associated with sodium imbalance; dehydration may occur, but not hypernatremia as a primary effect.

Take home points:

- Early aspirin poisoning: Hyperpnea (respiratory alkalosis).

- Progressive poisoning: Metabolic acidosis, hypoglycemia, fever, confusion, tinnitus.

- Nursing priorities: ABCs, notify poison control, prepare for gastric decontamination (activated charcoal), and monitor acid-base status.

- Severe cases: May require IV fluids, bicarbonate therapy, or hemodialysis.

When treating a child in hypovolemic shock, what is the recommended initial fluid bolus?

Explanation

Fluid resuscitation is the cornerstone of managing hypovolemic shock in children. The choice of fluid type, volume, and rate is critical, since children decompensate quickly once compensatory mechanisms fail.

Rationale for correct answer:

2. The recommended initial bolus for children in hypovolemic shock is 20 mL/kg of an isotonic crystalloid (Normal Saline or Ringer’s Lactate). Administered rapidly (over 5–10 minutes) and reassessed after each bolus. Isotonic crystalloids expand intravascular volume effectively, restoring perfusion without causing fluid shifts that worsen edema.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Dextrose-containing solutions are hypotonic once metabolized, and they do not remain in the intravascular space. They risk worsening cerebral edema in shock.

3. Hypotonic fluids such as 0.45% NS move into cells, not the intravascular space, and are dangerous in shock.

4. Colloids such as albumin and starches are not first-line in children; crystalloids are safer, cheaper, and equally effective.

Take home points

- Initial pediatric hypovolemic shock fluid bolus = 20 mL/kg isotonic crystalloid (NS or RL).

- Administer rapidly, reassess, and repeat if needed (up to 60 mL/kg before considering inotropes).

- Avoid hypotonic and dextrose-containing solutions in shock resuscitation.

- Colloids are not recommended first-line in pediatric shock.

A preschool child was administered activated charcoal in the emergency department after a poisoning event. The child is being discharged home. Which of the following adverse reactions to the medication should the parent be advised to report to the child’s primary health-care provider?

Explanation

Activated charcoal is commonly used in pediatric poisonings because it binds toxins in the gastrointestinal tract, reducing systemic absorption. It is generally safe, but serious complications can occur if it is aspirated into the lungs or if the child develops decreased responsiveness.

Rationale for correct answers:

4. Constipation is the most concerning adverse effect of activated charcoal, as it may progress to bowel obstruction or ileus. Parents should monitor for abdominal pain, distension, or absent bowel movements and notify the provider immediately if these occur.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. A Rash is not a typical side effect of activated charcoal.

2. Conjunctivitis is not associated with activated charcoal therapy.

3. Lethargy could relate to poisoning itself but not a direct adverse effect of activated charcoal.

Take home points

- Activated charcoal binds toxins in the GI tract and prevents absorption.

- Most common adverse effect: constipation (serious if bowel obstruction develops).

- Parents should report severe constipation, abdominal distension, or vomiting.

- Encourage adequate hydration and stool monitoring at home after discharge.

Practice Exercise 3

A parent brings their 2-year-old child to the clinic for a routine check-up. The child lives in a house built in 1950. What is the most appropriate action for the nurse?

Explanation

Lead exposure remains a serious health concern for children, particularly those living in older homes built before 1978, when lead-based paint was commonly used. Young children are at higher risk because they explore their environment orally and absorb lead more readily than adults.

Rationale for correct answer:

3. Children living in homes built before 1978 are at high risk for lead exposure from deteriorating paint and contaminated dust. The CDC and AAP recommend blood lead level (BLL) testing for at-risk children, particularly ages 1–2 years. Screening allows early identification and intervention before irreversible effects such as cognitive impairment, behavioral issues, and developmental delays occur.

Rationale for Incorrect Answers:

1. Chelation is indicated only for children with elevated blood lead levels (typically >45 mcg/dL). Starting it without testing is inappropriate.

2. Advising the parents that lead poisoning is a myth is incorrect and dangerous. Lead poisoning is a well-documented cause of serious pediatric morbidity.

4. Recommending a high-protein diet to prevent lead absorption is incorrect. Nutrition such as iron, calcium, and vitamin C can help reduce absorption, but it does not replace the need for screening.

Take home points

- Screen children at risk (especially ages 1–2 living in older homes) with a blood lead test.

- Chelation therapy is used only for confirmed, high blood lead levels.

- Prevention strategies: eliminate environmental sources (paint, dust, contaminated water).

- Nutrition helps, but it cannot prevent or treat poisoning without addressing exposure.

A 4-year-old child is pulled from a swimming pool unresponsive. What is the most critical immediate intervention?

Explanation

In pediatric drowning victims, the primary problem is respiratory arrest leading to hypoxemia, not cardiac in origin.

Rationale for correct answer:

2. According to Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS) guidelines if a child is unresponsive and not breathing, the rescuer should start with 2 rescue breaths to provide oxygen. After delivering the breaths, check for a pulse for no more than 10 seconds. If there is no pulse, begin chest compressions. Early rescue breaths are critical because oxygen deprivation is the main cause of cardiac arrest in drowning.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Beginning chest compressions is appropriate if the child has no pulse, but in drowning, the immediate problem is lack of oxygen. Rescue breaths come first.

3. Administering IV fluids is not the initial intervention in an unresponsive drowning victim. Airway and breathing take priority.

4. Checking for a pulse is important, but rescue breaths should not be delayed; hypoxemia must be corrected first.

Take home points

- In pediatric drowning: Airway and breathing are the priority.

- Always begin with 2 rescue breaths, then assess pulse.

- If no pulse, start CPR at 15:2 (two rescuers) or 30:2 (single rescuer).

- Early oxygenation significantly improves survival and neurological outcomes.

Which of the following statements about pediatric drowning is correct?

Explanation

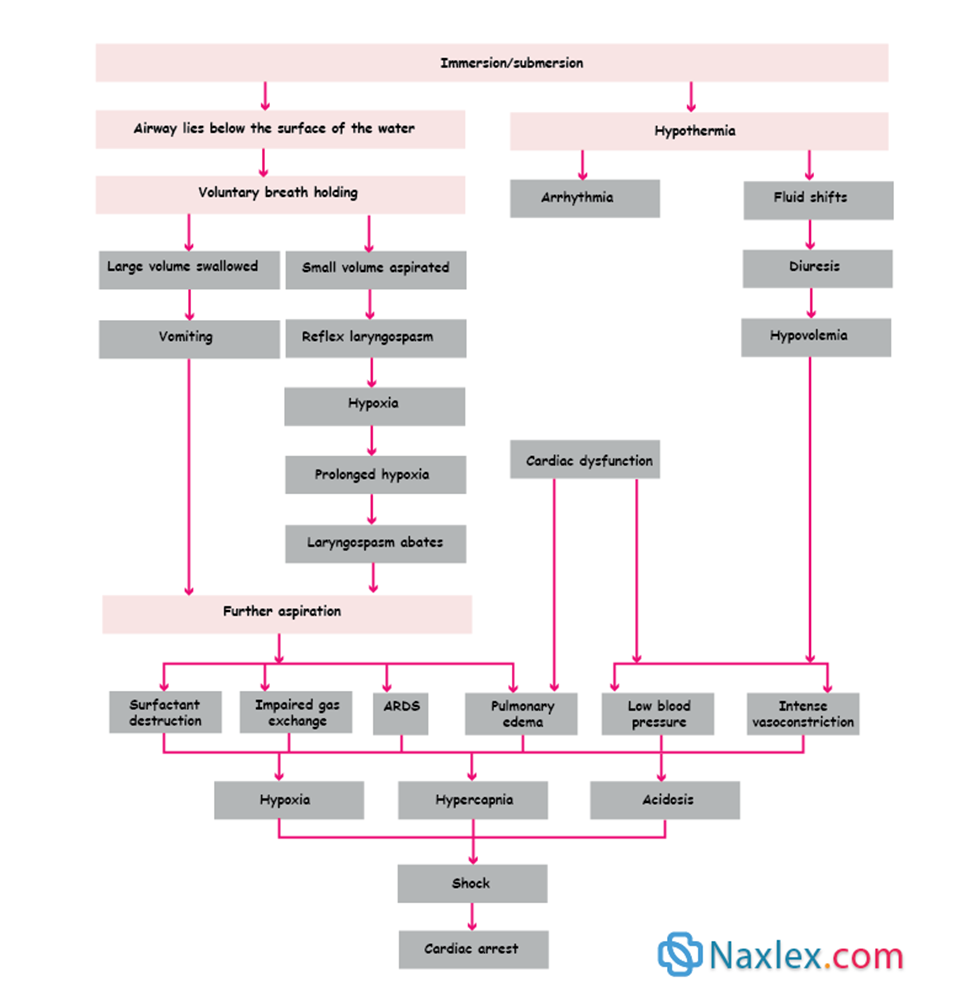

Drowning in pediatrics refers to a process of respiratory impairment due to submersion or immersion in liquid, regardless of outcome. Highest risk in children aged 1–4 years, often due to lack of supervision and access to water sources like bathtubs, pools, or buckets.

Rationale for correct answer:

3. In pediatric drowning, hypothermia may provide neuroprotection by slowing cellular metabolism and reducing oxygen demand. This is sometimes called the “diving reflex” in children, where immersion in cold water triggers bradycardia, peripheral vasoconstriction, and preferential blood flow to vital organs such as the heart and brain. While hypothermia complicates resuscitation, it can extend the window of time for potential recovery with intact neurological function.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Most drownings are a result of suicide: In children, drowning is usually accidental (e.g., bathtubs, pools, buckets). Suicide-related drowning is rare in pediatrics.

2. Drowning can only occur in deep water: Children can drown in very shallow water, as little as a few centimeters, such as bathtubs, toilets, or buckets.

4. Children are less susceptible to drowning than adults: Children are more susceptible due to smaller body size, curiosity, limited motor skills, and lack of safety awareness.

Take home points

- Pediatric drowning is usually accidental and can occur even in shallow water.

- Hypoxemia is the primary cause of morbidity and mortality.

- Hypothermia may be protective, but also complicates resuscitation.

- Prevention (supervision, barriers, safety education) is the most effective strategy.

A 1-year-old is suspected of having chronic lead poisoning. Which of the following is a classic manifestation of chronic lead exposure in children?

Explanation

Drowning in pediatrics refers to a process of respiratory impairment due to submersion or immersion in liquid, regardless of outcome. Highest risk in children aged 1–4 years, often due to lack of supervision and access to water sources like bathtubs, pools, or buckets.

Rationale for correct answer:

1. Pica, the compulsive ingestion of non-food substances such as paint chips, dirt, or plaster, is a classic manifestation of chronic lead poisoning in children. Children with lead exposure may develop anemia, developmental delay, cognitive impairment, and behavioral issues, but pica is particularly characteristic because it not only results from lead exposure but also perpetuates it, by increasing ingestion of contaminated materials.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

2. While behavioral changes like irritability or decreased attention span may occur with lead poisoning, hyperactivity is nonspecific and not considered a classic hallmark.

3. Chronic lead poisoning can cause hypertension, but this is more common in adults due to long-term vascular and renal effects, not typically in young children.

4. Decreased lead level is not a manifestation but rather an expected outcome after treatment such as chelation therapy.

Take home points

- Pica is the classic sign of chronic lead poisoning in children.

- Other features include anemia, learning difficulties, irritability, abdominal pain, and growth delay.

- Children are most at risk due to their developing nervous system and tendency for hand-to-mouth activity.

- Screening is essential in high-risk homes (e.g., pre-1978 housing, peeling paint).

The most important initial intervention for any pediatric poisoning is:

Explanation

Poisoning in children is the result of ingesting, inhaling, absorbing through the skin, or injecting toxic substances such as medications, household chemicals, plants, or gases.

Rationale for correct answer:

2. The most important initial intervention in any pediatric poisoning is to call the Poison Control Center immediately. Poisoning management depends on the type of substance, amount ingested, time since ingestion, and child’s condition. Poison Control provides evidence-based, situation-specific instructions, such as whether to observe at home, go to the ED, administer activated charcoal, or prepare for antidote therapy.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Inducing vomiting is no longer recommended because it can cause aspiration or esophageal injury, especially with caustic substances or hydrocarbons.

3. Administering activated charcoal is effective for many ingestions if given within 1 hour, but should only be used after professional guidance, since it is contraindicated in some poisonings such as heavy metals and corrosives.

4. Preparing for gastric lavage is rarely used today, and only in very specific, life-threatening ingestions, due to risk of aspiration and complications.

Take home points

- First step in pediatric poisoning: Call Poison Control.

- Do not induce vomiting unless specifically instructed.

- Activated charcoal is useful but only after professional guidance.

- Management is substance-specific, so consultation is crucial.

Comprehensive Questions

A nurse observes a 6-year-old child fall from a 3rd-story window. The area is safe for the nurse to intervene. There is no one else in the area. Which of the following actions should the nurse perform first?

Explanation

In pediatric emergencies, the priority is airway, breathing, and circulation (ABC). After ensuring the scene is safe, the nurse should first determine whether the child is breathing before proceeding with further interventions.

Rationale for correct answer:

1. Airway and breathing come before circulation. If the child is not breathing, immediate rescue breaths and CPR must follow. This aligns with pediatric basic life support (BLS) guidelines, which emphasize checking responsiveness and breathing before pulse assessment in children.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

2. Assessing the carotid pulse is important for circulation, but in pediatric assessment, breathing is checked first. If the child is not breathing, interventions must begin without delay.

3. Accessing for emergency assistance by calling for help is critical, but since the nurse is alone and already at the scene, a rapid assessment of breathing ensures no delay in initiating life-saving support. Once responsiveness and breathing are assessed, emergency help should be activated.

4. Administering rescue breaths is only done after confirming that the child is not breathing. Starting rescue breaths without assessment risks providing unnecessary or inappropriate care.

Take home points

- Primary survey in pediatric emergencies follows ABC: Airway, Breathing, Circulation.

- Check breathing before pulse in children is different from adults where both are checked together.

- The order of events in pediatric emergencies is scene safety first then quick assessment then call for help and initiate CPR if needed.

- Nurses must act quickly but systematically to prevent overlooking critical steps.

A nurse is administering cardiopulmonary resuscitation as a 1-person rescuer to an infant who was found not breathing and with no pulse. Which of the following actions should the nurse perform?

Explanation

For an infant with no pulse, the American Heart Association (AHA) pediatric basic life support (BLS) guidelines state that a single rescuer should perform CPR using a 30:2 compression-to-breath ratio. This ensures adequate circulation and oxygenation until help or an AED becomes available.

Rationale for correct answer:

4. In 1-rescuer infant CPR, compressions are done with 2 fingers in the center of the chest, just below the nipple line, at a depth of about 1.5 inches (4 cm) and at a rate of 100–120 compressions per minute. The 30:2 ratio maximizes perfusion while allowing for effective ventilation.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Compressing the child’s chest with the palm of 1 hand is used for children (age 1–puberty), not infants. Infants require 2 fingers (single rescuer) or the 2-thumb encircling technique (two rescuers).

2. Obtaining an AED as soon as possible is important, but as a lone rescuer, the nurse should initiate CPR immediately first. If no help is available, CPR should be performed for about 2 minutes before leaving the infant to get an AED.

3. Accessing emergency assistance (call 911) as soon as possible is critical, but again, when alone with an infant who is pulseless and not breathing, CPR must be started first for 2 minutes, then the rescuer should call for help and get an AED.

Take home points:

- Infant CPR (1 rescuer): 30 compressions to 2 breaths, using 2 fingers.

- Infant CPR (2 rescuers): 15 compressions to 2 breaths, using the 2-thumb encircling technique.

- Depth: ~1.5 inches (4 cm) in infants, ~2 inches (5 cm) in children.

- Rate: 100–120 compressions/min.

- Sequence: If alone is to perform CPR 2 minutes then call for help and get an AED.

Two nurses are providing cardiopulmonary resuscitation on a 6-year-old child who collapsed on the school playground. Which of the following actions should the nurses perform?

Explanation

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in children (ages 1 year to puberty) requires modifications compared to infants and adults. When two rescuers are present, compressions and ventilations are better coordinated, and the compression-to-breath ratio is different from that of a single rescuer. Chest compression depth and early AED use are critical factors that directly influence survival.

Rationale for correct answer:

2. Chest compression depth of 2 inches is the recommended depth for effective compressions in children. It ensures adequate circulation during CPR while avoiding injury from excessive force.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. 30 compressions to 2 breaths ratio applies to single-rescuer CPR for children. Since there are two nurses (two rescuers), the correct ratio is 15 compressions to 2 breaths, not 30:2.

3. Obtain the automated external defibrillator after 2 minutes – AED use should be as soon as it becomes available, not delayed. Early defibrillation greatly improves survival in cardiac arrest.

4. CPR should be continued until return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), arrival of advanced help, or when the rescuer is too exhausted to continue. Time is not fixed at 2 hours.

Take home points

- Child CPR (1–puberty):

- Depth: about 2 inches (5 cm).

- Rate: 100–120 compressions/min.

- Ratio: 30:2 (1 rescuer), 15:2 (2 rescuers).

- AED: Use as soon as available. Pediatric dose preferred, but adult AED can be used if no pediatric pads are present.

- CPR is continued until ROSC, advanced care, or rescuer exhaustion not based on a fixed time.

While supervising lunchtime in an elementary school, a school nurse observes a child abruptly stand up and appear to be gagging. Which of the following actions should the nurse perform at this time?

Explanation

Choking is a common emergency in school-age children due to the risk of food aspiration. The nurse must quickly determine whether the airway obstruction is partial or complete. Management differs depending on the severity of obstruction, and immediate, appropriate action can prevent respiratory arrest.

Rationale for correct answer:

2. Assessing whether the child is able to cough effectively is the first action because determining if the obstruction is partial or complete guides further interventions. If the child can cough forcefully, encourage coughing. If the airway is completely obstructed, perform abdominal thrusts (Heimlich maneuver).

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Informing the child to remain seated while eating is preventive advice, not an appropriate intervention in an active choking emergency.

3. Slapping the child five times between the shoulder blades are recommended for infants (<1 year), not for school-age children.

4. Standing behind the child and place both fists under the rib cage (Heimlich maneuver) is correct if the child is unable to cough, speak, or breathe, but assessment must come first.

Take home points

- First action in choking is to assess if cough is effective.

- For partial obstruction encourage coughing, do not interfere.

- For complete obstruction, perform abdominal thrusts (Heimlich maneuver) in children >1 year.

- Infants (<1 year): Use 5 back blows and 5 chest thrusts instead of abdominal thrusts.

A nurse has determined that a 10-month-old child has an obstructed airway. The child is making no vocalizations and is not breathing. Which of the following actions by the nurse is appropriate at this time?

Explanation

Infants under 1 year who develop a severe airway obstruction require immediate intervention because they cannot effectively cough or perform protective maneuvers. Unlike older children and adults, infants do not receive abdominal thrusts (Heimlich maneuver).

Rationale for correct answer:

1. While tipping the child’s head down, slap the child five times between the shoulder blades: This is the first step in infant choking management. The infant should be supported face down on the rescuer’s forearm, head lower than chest, while delivering firm back blows. If ineffective, 5 chest thrusts are performed, alternating until the object is expelled or the infant becomes unresponsive.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

2. Peer inside the child’s mouth and look for the obstruction: Only perform a visual check if the object is clearly visible. Routine inspection wastes critical time.

3. Insert the pinky finger into the child’s mouth and sweep the mouth: Blind finger sweeps are contraindicated in infants because they may push the object deeper and worsen obstruction.

4. Perform upward thrusts with fists placed under the rib cage: Abdominal thrusts (Heimlich maneuver) are not safe for infants <1 year due to risk of organ injury.

Take home points:

- Infants (<1 year) with airway obstruction: Alternate 5 back blows and 5 chest thrusts until object is expelled or infant becomes unresponsive.

- No blind finger sweeps, only remove visible objects.

- Abdominal thrusts are reserved for children >1 year and adults.

- If the infant becomes unresponsive, begin CPR, starting with chest compressions, and check airway for visible object before giving breaths.

A nurse has completed an emergency assessment on a 3-year-old child who has just started to cry. While conducting the secondary assessment, the nurse should ask the parent which of the following questions? Select all that apply

Explanation

In pediatric emergencies, assessment follows the primary survey (ABCDEs: Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability, Exposure) and then the secondary survey, which focuses on history gathering and detailed examination. The secondary assessment often uses the mnemonic SAMPLE history (Signs/symptoms, Allergies, Medications, Past medical history, Last meal, Events leading to injury/illness).

Rationale for correct answers:

1. “Where is the child’s injury?” Helps pinpoint the site and severity of injury during the secondary survey.

2. “Does your child have allergies?” Critical for safe medication administration and identifying risks (e.g., latex, food, or drug allergies).

5. “What was the child doing before he was injured?” Provides context and mechanism of injury, which is essential in pediatric trauma assessment.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

3. “When is your child due to eat next?” The focus should be on the last oral intake (as per SAMPLE history), not when the child is due to eat next. This option does not provide useful emergency information.

4. “Does your child know how to swim?” This is not relevant to the current emergency unless the injury was drowning-related. This question does not contribute to immediate secondary assessment.

Take home points:

- Secondary assessment in pediatric emergencies uses SAMPLE history.

- Key areas: site of injury, allergies, medications, past history, last intake, and events before the incident.

- Questions should always relate to safety, mechanism of injury, and medical background.

- Avoid unrelated or non-urgent questions that do not aid emergency care.

A child, who is bleeding heavily, is in hypovolemic shock. The nurse determines that the child is currently compensating for the loss of blood when the nurse notes which of the following?

Explanation

Hypovolemic shock in children results from significant fluid or blood loss, leading to decreased circulating volume and impaired tissue perfusion. Children initially compensate through mechanisms such as peripheral vasoconstriction to maintain perfusion.

Rationale for correct answer:

1. Tachycardia is the body’s first compensatory response to blood loss, attempting to maintain cardiac output and tissue perfusion despite decreased circulating volume.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

2. Hypotension is a late sign in pediatric hypovolemic shock, indicating decompensation and impending cardiovascular collapse.

3. Bradypnea is not a compensatory response; instead, children exhibit tachypnea in early shock to improve oxygen delivery. Bradypnea is a pre-terminal sign.

4. Cyanosis indicates severe hypoxemia and poor perfusion, occurring in advanced or decompensated shock, not during compensation.

Take home points

- Compensated hypovolemic shock in children: Tachycardia, tachypnea, cool extremities, delayed capillary refill.

- Decompensated shock: Hypotension, altered mental status, weak pulses.

- Late/irreversible signs: Bradypnea, cyanosis, and cardiac arrest.

- Nursing focus: Early recognition of tachycardia and perfusion changes and implementation of rapid fluid/blood replacement and airway support.

A 3-year-old with a history of gastroenteritis is brought in by his parents. He has not had a wet diaper in 12 hours, is lethargic, and has a sunken fontanelle. His heart rate is 160 bpm and his blood pressure is 80/40 mmHg. What type of shock is he most likely experiencing?

Explanation

Children are especially vulnerable to fluid losses due to higher metabolic rates and a larger proportion of body water compared to adults. Conditions like gastroenteritis can quickly lead to dehydration and hypovolemia, which, if severe, progress to shock. Recognizing the cause of shock is essential for prompt and targeted management.

Rationale for correct answer:

3. Hypovolemic shock is the most common type of pediatric shock and results from fluid loss such as vomiting, diarrhea, and hemorrhage. This child has classic features including a history of gastroenteritis, no urine output, sunken fontanelle, tachycardia, and hypotension.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Cardiogenic shock is caused by impaired cardiac function (e.g., myocarditis, congenital heart disease). Would present with poor perfusion plus pulmonary edema or hepatomegaly, not dehydration signs.

2. Distributive shock is seen in sepsis or anaphylaxis. Characterized by warm extremities, bounding pulses, and wide pulse pressure early on, not the cool extremities and dehydration signs here.

3. Obstructive shock is caused by physical obstruction to blood flow (e.g., cardiac tamponade, tension pneumothorax). Would not be explained by gastroenteritis and dehydration.

Take home points

- Hypovolemic shock is caused by fluid loss (vomiting, diarrhea, bleeding) and results in symptoms such as tachycardia, poor perfusion, eventually hypotension.

- In pediatrics, hypotension is a late sign, meaning this child is already in decompensated hypovolemic shock.

- First-line management include rapid isotonic fluid resuscitation (20 mL/kg normal saline or Ringer’s lactate bolus).

The greatest threat to life as a result of dehydration in children is:

Explanation

Dehydration in children is a common and potentially life-threatening condition, especially due to their higher body water content and faster fluid turnover compared to adults. Severe dehydration can rapidly progress to hypovolemic shock, which impairs tissue perfusion and oxygen delivery, making it the most dangerous complication if not treated promptly.

Rationale for correct answer:

2. The greatest threat in pediatric dehydration is hypovolemic shock, caused by extreme fluid loss and decreased intravascular volume. Shock compromises oxygen delivery to vital organs (brain, heart, kidneys), leading to organ failure and death if not corrected.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Oliguria is a sign of decreased renal perfusion but not the most immediate life-threatening consequence.

3. Arrhythmia can occur secondary to electrolyte imbalance, but it is not the primary or greatest threat in dehydration.

4. Hypotension is a late sign of shock; the underlying problem is circulatory collapse (shock), not just low blood pressure.

Take home points

- Shock is the most life-threatening complication of dehydration in children.

- Early signs: tachycardia, delayed capillary refill, irritability, cool extremities.

- Late signs: hypotension, lethargy, weak pulses, indicate impending cardiovascular collapse.

- Nursing priority: rapid fluid replacement (oral rehydration if mild/moderate, IV fluids if severe).

A nurse working in a preschool discovers that a 2½-year-old child has drunk a bottle of red paint.

Place the following nursing actions in the correct order of priority.

Explanation

Poisoning is a frequent pediatric emergency, especially in toddlers and preschoolers due to curiosity and exploration. When ingestion is suspected, the nurse must follow a priority sequence where assessment and stabilization always come before notifications.

Rationale for correct order:

4. Assess the child for adverse effects: First priority in any poisoning case is assessing the child’s immediate condition (airway, breathing, circulation, consciousness, and signs of toxicity).

3. Call the poison control center: After ensuring stability, the next step is contacting poison control for specific management instructions based on the type of paint ingested.

1. Notify the child’s parents: Parents must be informed promptly after immediate assessment and initiation of interventions.

2. Question the teacher about the incident: Gathering background details (amount ingested, time of ingestion, type of paint) is important, but it comes after ensuring the child’s safety and contacting poison control.

Take-Home Points

- Priority in pediatric poisoning:

- Immediate assessment of the child’s status.

- Activate resources (Poison Control/911 if life-threatening).

- Notify parents/caregivers.

- Gather incident details for reporting and prevention.

- Nurses should never delay assessment for reporting.

A 2-year-old child’s blood lead level is 4 micrograms per dL. Based on the data, which of the following actions should the nurse take?

Explanation

Lead exposure remains a serious health concern for children, particularly those living in older homes built before 1978, when lead-based paint was commonly used. Young children are at higher risk because they explore their environment orally and absorb lead more readily than adults.

Rationale for correct answer:

4. A blood lead level of 4 µg/dL is below the CDC reference value of 5 µg/dL (threshold for concern). No medical treatment such as chelation is indicated at this level. The best nursing action is primary prevention, including environmental hygiene and personal hygiene, such as frequent handwashing, washing toys, and avoiding contaminated surfaces.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Notify the department of health is required only if the blood lead level is ≥5 µg/dL (per CDC guidelines).

2. Chelation therapy is recommended only for blood lead levels of ≥45 µg/dL.

3. Lead exposure usually occurs in the home environment (old paint, dust, contaminated soil, water), so educating the teacher is not the priority intervention.

Take home points:

- For blood lead levels <5 µg/dL the focus on prevention and parental education.

- Blood levels 5–44 µg/dL, repeat testing, eliminate sources of exposure, but no chelation.

- For blood levels ≥45 µg/dL, chelation therapy indicated.

- Nurses play a key role in educating parents about handwashing, wet-mopping floors, frequent cleaning of toys, and avoiding lead-contaminated environments.

A child is receiving oral Chemet (succimer) for a BLL of 48 micrograms/dL. For which of the following side effects should the child be monitored?

Explanation

Lead poisoning in children is a serious condition that can cause neurological, hematological, and developmental complications. When blood lead levels (BLL) reach ≥45 µg/dL, chelation therapy is recommended.

Rationale for correct answer:

1. Chemet (succimer) is an oral chelating agent used in children with BLLs ≥45 µg/dL. A serious side effect is neutropenia (low WBC count), which increases the child’s risk for infection. Therefore, monitoring the WBC count is essential during therapy.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

2. Platelet count below 400,000 cells/mm³ is still within the normal range (150,000–400,000/mm³). Thrombocytopenia is not a primary concern with succimer.

3. Normal potassium levels are 3.5–5.0 mEq/L; a value above 3.5 is expected and not a side effect of succimer.

4. Serum sodium above 135 mEq/L is normal, not related to succimer toxicity.

Take home points

- Succimer (Chemet) is an oral chelating agent for moderate lead poisoning (BLL ≥45 µg/dL).

- The most important adverse effect is neutropenia, so WBC counts must be monitored.

- Chelation therapy does not usually disturb sodium or potassium balance.

- Parent teaching should include monitoring for fever, sore throat, or other signs of infection due to risk of decreased WBCs.

A child is receiving IV calcium disodium versenate (CaNa2EDTA). For which of the following serious side effects should the child be monitored? Select all that apply

Explanation

Calcium disodium versenate (CaNa₂EDTA) is an IV chelating agent used in children with moderate to severe lead poisoning (typically BLL ≥45 µg/dL when oral therapy is not tolerated, or ≥70 µg/dL as first-line therapy). While effective in binding lead for urinary excretion, it can have serious systemic side effects, mainly affecting the neurological and renal systems, so close monitoring is required during therapy.

Rationale for correct answers:

1. CaNa₂EDTA may cause hypocalcemia (by binding calcium along with lead) or rapid shifts in electrolytes, which can precipitate seizures and other neurotoxic effects.

4. Because calcium is mobilized with the chelation process, electrolyte disturbances including hypercalcemia may develop, requiring close monitoring of calcium levels.

5. Elevated serum creatinine – Nephrotoxicity is a major adverse effect. EDTA can damage the renal tubules, so renal function (BUN, creatinine, urine output) must be monitored closely.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

2. Hypertension is not typically associated with CaNa₂EDTA. Hypotension may occur in rare cases due to infusion reactions, but hypertension is not a known effect.

3. Hyperglycemia is unrelated to CaNa₂EDTA therapy; it does not affect glucose metabolism.

Take home points

- CaNa₂EDTA is an IV chelator used for significant lead poisoning.

- Two most dangerous complications:

- Neurotoxicity (e.g., seizures, hypocalcemia signs).

- Nephrotoxicity (elevated creatinine, decreased urine output).

- Nurses should:

- Monitor neuro status and seizure activity.

- Check renal labs (BUN, creatinine) and I/O.

- Ensure adequate hydration to reduce nephrotoxic risk.

A 3-year-old child’s blood lead level measures 12 micrograms/dL. The nurse would expect the child to exhibit which of the following signs/symptoms?

Explanation

Lead poisoning is a preventable but serious pediatric condition. Blood lead levels (BLL) ≥5 µg/dL are considered elevated. Children with BLL 10–20 µg/dL often present with mild behavioral and developmental changes, even before major neurological or hematological effects appear. Subtle symptoms, such as irritability and aggression, are common early indicators.

Rationale for correct answer:

3. Aggression is an early neurobehavioral manifestation of lead toxicity. Even at relatively low levels (10–20 µg/dL), children may show irritability, hyperactivity, decreased attention span, and aggressive behavior, reflecting the neurotoxic effects of lead on the developing brain.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Hyponatremia: Lead does not directly alter sodium balance; electrolyte abnormalities are not typical in mild lead poisoning.

2. Polycythemia: Lead can cause anemia, not polycythemia. It interferes with hemoglobin synthesis, leading to microcytic, hypochromic anemia.

4. Polyphagia: This is not associated with lead toxicity. Instead, children may develop loss of appetite, abdominal pain, or constipation at higher levels.

Take home points

- BLL ≥5 µg/dL is abnormal; 12 µg/dL indicates mild but concerning exposure.

- Behavioral changes (aggression, irritability, hyperactivity) are early warning signs.

- Higher levels can lead to anemia, cognitive impairment, seizures, and encephalopathy.

- Nursing care should focus on parent education, environmental modifications, and regular monitoring of BLL.

A nurse discovers an 8-month-old child face down in a puddle of water. The child is not breathing and has no pulse. Which of the following actions should the nurse perform at this time?

Explanation

Pediatric basic life support (BLS) guidelines emphasize rapid recognition of cardiac arrest, initiation of CPR, and timely activation of emergency response. In infants, drowning and respiratory failure are common causes of cardiac arrest.

Rationale for correct answer:

2. For an infant with no breathing and no pulse, the priority is to initiate CPR. A single rescuer should use a 30:2 compression-to-breath ratio. After about 2 minutes of CPR, the rescuer should leave to call 911 and obtain an AED if not already done.

Rationale for incorrect answers

1. 5 back slaps followed by 5 chest thrusts is the technique for a conscious infant with a foreign body airway obstruction, not for cardiac arrest.

3. Rescue breaths every 3–5 seconds is appropriate for respiratory arrest with a pulse, but this infant has no pulse, so full CPR is required.

4. If alone, the nurse should start CPR first for 2 minutes before activating emergency response in infants and children.

Take home points

- For infants and children:

- No pulse & no breathing: CPR (30:2 for 1 rescuer, 15:2 for 2 rescuers).

- If alone: CPR first for 2 minutes, then call 911.

- If not alone: one rescuer calls 911 while the other begins CPR.

- Back slaps/chest thrusts are for airway obstruction in a conscious infant, not cardiac arrest.

- Always reassess pulse and breathing every 2 minutes during CPR.

Exams on Nursing care during a pediatric emergency

Custom Exams

Login to Create a Quiz

Click here to loginLessons

Naxlex

Just Now

Naxlex

Just Now

Notes Highlighting is available once you sign in. Login Here.

Objectives

- Understand the unique anatomical and physiological differences in children that impact emergency care.

- Understand the systematic approach to initial and secondary assessment of an ill or injured child.

- Understand how to perform age-appropriate Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR).

- Gain knowledge on the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of shock.

- Understand the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of trauma in pediatrics.

- Understand the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of acute poisonings

- Gain knowledge on the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of chronic heavy metal poisoning.

- Gain knowledge on the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of drowning.

- Identify key nursing diagnoses and interventions for various pediatric emergency situations.

Introduction

- Pediatric emergencies present a unique set of challenges due to the significant physiological and developmental differences between children and adults.

- Children are not simply "small adults"; their anatomy, metabolism, and psychological responses to illness and injury differ dramatically.

- The foundation of pediatric emergency care rests on a thorough understanding of the developmental stages and their impact on presentation and response to illness or injury. For example, an infant's large head size relative to their body makes them susceptible to head trauma, while their short, narrow, and more pliable airway can be easily compromised.

- Their higher metabolic rate and larger body surface area-to-weight ratio increase their risk for fluid and heat loss, and their underdeveloped immune systems make them more prone to severe infections.

- Furthermore, a child's psychological state and a parent's presence are critical factors in providing care; a calm, reassuring approach is essential for gaining a child's cooperation and alleviating parental anxiety.

- This document outlines the critical components of pediatric emergency care, starting with the fundamental principles of assessment and moving into specific clinical conditions.

- It is crucial that nurses are proficient in initial rapid assessment, which is the cornerstone of emergency care, to quickly identify life-threatening conditions.

Emergent Care

3.1. Initial Assessment

A systematic approach to assessing a critically ill or injured child is the cornerstone of effective emergent care. This process should be rapid and focused on identifying and correcting life-threatening conditions.

- Check for Safety: Before approaching the child, ensure the scene is safe for both you and the child. This includes checking for hazards like traffic, fire, or live electrical wires.

- Awaken the Child: Gently try to awaken the child by tapping their shoulder or the sole of their foot (for an infant) and asking if he or she is okay. Adding the child’s name, if it is known, may improve the possibility of the child responding. Use the AVPU scale (Alert, Verbal, Pain, Unresponsive) to assess their level of consciousness. When attempting to arouse the child, the nurse should be careful not to cause additional injury. In the case of a fall, for example, the neck should not be moved, if possible, to prevent injury to the spinal cord.

- Get Help: If the child fails to respond, the nurse should assume the worst and should shout “Help!” to attract the attention of others who can assist in the care of the child. If no one is available to assist, the nurse should care for the child for 2 full minutes, then leave the child and go to call for emergency personnel (e.g., call 911).

- Assess for Breathing: Look, listen, and feel for breathing. Look for chest rise and fall. Listen for breath sounds. Feel for air movement from the nose or mouth. Normal breathing should be effortless and quiet. Gasping is not considered effective breathing. If the child is not breathing at all or is only gasping for breath, the nurse should assume that the child is in need of resuscitation.

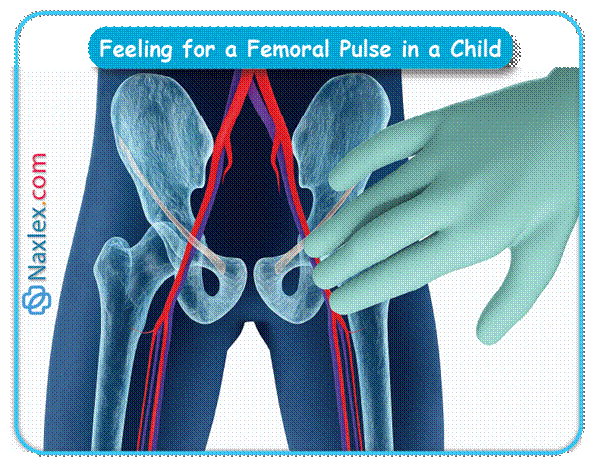

- Assess for a Pulse: This procedure should take no longer that 10 seconds.

- Infant (<1 year): Check the brachial pulse on the inside of the upper arm. This is because the carotid and femoral pulses are difficult to assess at this age.

-

- Child (1 year to puberty): Check the carotid or femoral pulse.

- Adolescent (puberty and older): Check the carotid pulse.

- If the pulse rate is greater than or equal to 60 bpm, rescue breaths should be administered at a rate of one every 3 to 5 sec (i.e., 12 to 20 per min).

- If the pulse rate is less than 60 bpm, and the child is exhibiting signs of poor oxygenation (e.g., pale, cyanotic), cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) should be begun.

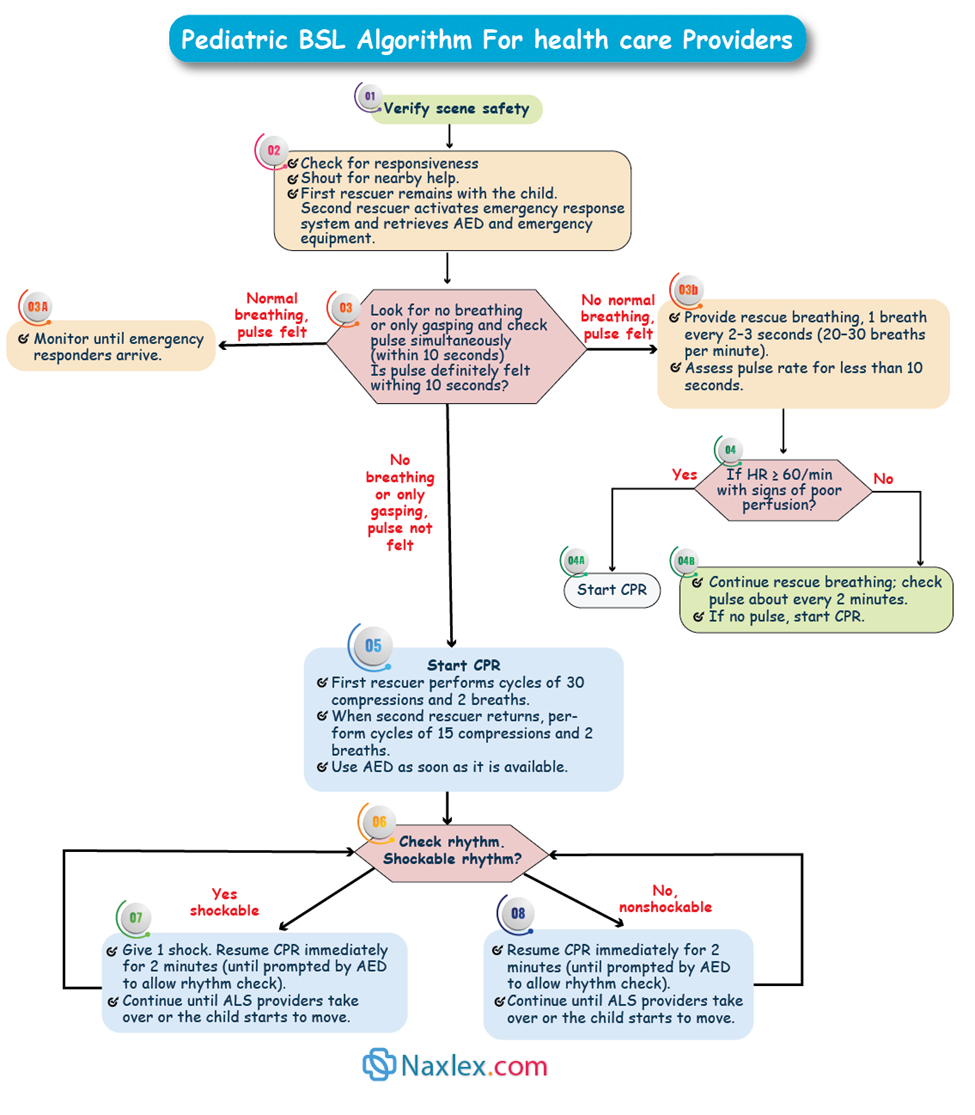

- Perform Age-Appropriate CPR (Acronym CAB): The standard CPR sequence has been updated to C-A-B (Compressions, Airway, Breathing) for most situations.

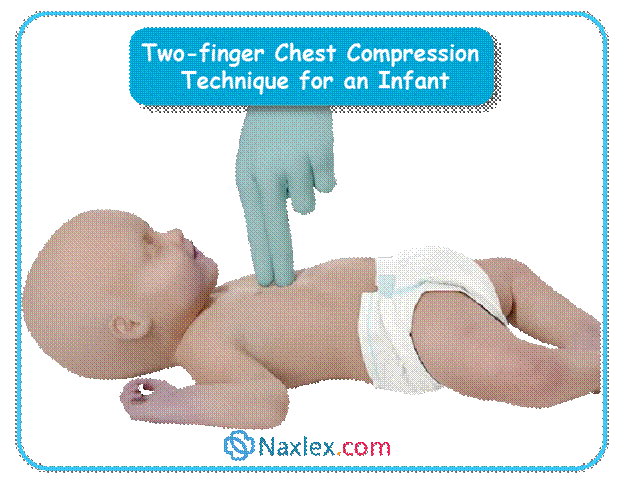

A. Infant CPR (under 1 year):

- Initial Step: If you are alone and a child suddenly collapses, call EMS first. If you find an unresponsive infant and do not witness the collapse, perform 2 minutes of CPR before calling for help. In addition, the nurse should obtain an automated external defibrillator (AED), if available.

- Circulation (Compressions):

- One-Rescuer Technique: Use two fingers placed on the sternum just below the nipple line.

-

- Two-Rescuer Technique: At the time the infant is discovered, rescuer one should begin CPR using the two-thumb encircling hands technique. Wrap your hands around the infant's chest and use your thumbs to compress the sternum. This method is more effective and less tiring. Rescuer two should immediately call for emergency assistance and obtain an AED, if available. Once rescuer two returns, rescuer one should stop CPR, ending with the compression phase, and the AED procedure should be followed. Following each AED intervention, rescuers one and two should alternate positions between performing chest compressions and rescue breaths.

-

- Compression Rate: 100-120 compressions per minute.

- Compression Depth: Approximately 1.5 inches (4 cm) or one-third of the chest diameter.

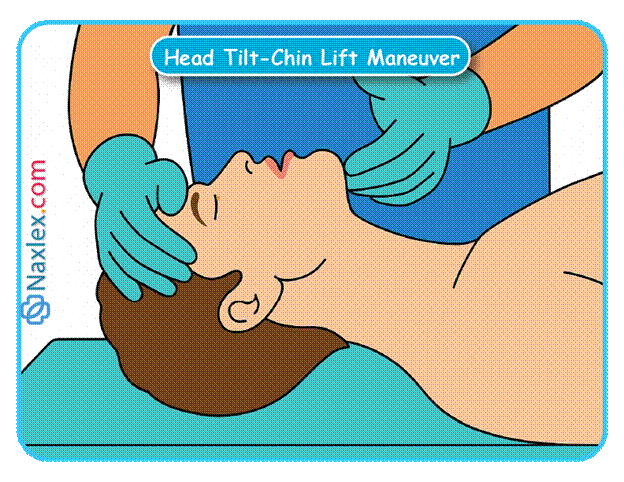

- Airway: Tilt the head back slightly and lift the chin to open the airway (sniffing position). Avoid overextending the neck.

- Breathing: Give two breaths over 1 second each, watching for visible chest rise. The ratio of compressions to breaths is 30:2 for one rescuer and 15:2 for two rescuers.

Nursing Insight: The AED should be used as soon as it is acquired. CPR should be stopped after the compression phase. The machine should be turned on. The AED pads should be applied to the infant’s chest, per machine instructions. (Adult pads may be used if the machine is not equipped with infant pads.). The AED prompts should be followed. After the AED sequence is complete, CPR should be resumed. An AED reanalysis and shock, if applicable, should be performed every 2 min or as prompted by the machine. The rescuer should continue CPR until emergency personnel arrive or until the child responds.

B. Child CPR (1 year to puberty):

- Initial Step: Call EMS immediately if you witness a child collapse. If the collapse is not witnessed, perform 2 minutes of CPR before calling.

- Circulation (Compressions):

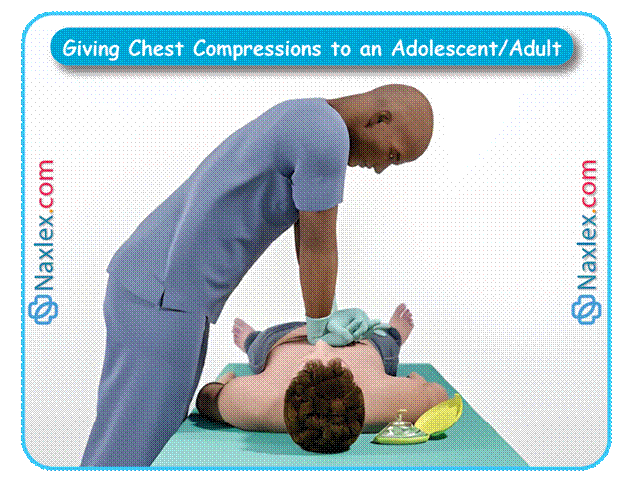

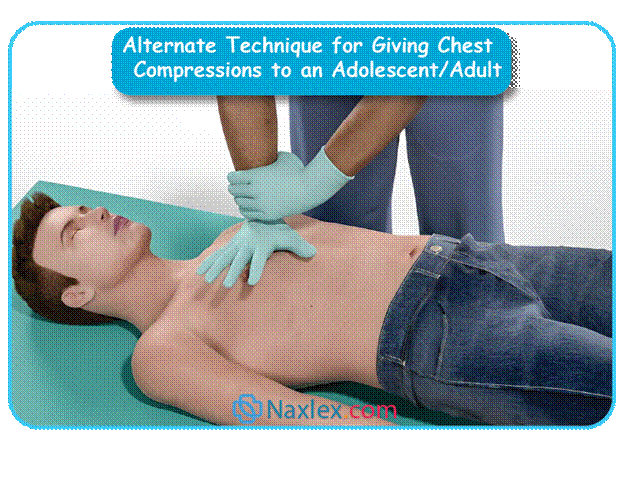

- Technique: Use the heel of one or two hands on the lower half of the sternum.

- Compression Rate: 100-120 compressions per minute.

- Compression Depth: Approximately 2 inches (5 cm) or one-third of the chest diameter.

- Airway: Use the head-tilt/chin-lift maneuver.

- Breathing: Give two breaths, each over 1 second, watching for chest rise. The ratio is 30:2 for one rescuer and 15:2 for two rescuers.

C. Adolescent CPR (puberty and older):

- Adult CPR criteria should be employed when the victim is past the pubertal period. The adult CPR procedure should be performed as follows:

- Responsiveness assessed.

- Breathing assessed.

- Emergency personnel notified and an AED obtained as soon as the victim is found to be unresponsive and not breathing or gasping.

- Pulse assessed for a maximum of 10 sec. If a pulse is present, rescue breaths should be provided every 5 sec. If a pulse is absent, CPR procedure should be begun.

- Circulation (Compressions):

- Technique: Use two hands, interlocked fingers, on the lower half of the sternum.

-

- Compression Rate: 100-120 compressions per minute.

- Compression Depth: At least 2 inches (5 cm).

- Airway: Use the head-tilt/chin-lift maneuver.

- Breathing: Give two breaths, each over 1 second. The ratio is 30:2 regardless of the number of rescuers.

Nursing Insight: The most likely cause of cardiopulmonary arrest in a child is different from that of an adult. In infants, the most common causes of cardiopulmonary arrest are congenital heart disease, sudden infant death syndrome, and prematurity. For children over 1 year of age, the most common causes of cardiopulmonary arrest are accidental injury and respiratory failure resulting from an acute or chronic upper respiratory illness. Except during the infancy period, cardiopulmonary arrest rarely is caused by a cardiac event as it is in adults.

3.2. Secondary Assessment

Once the immediate life threats have been managed, perform a more detailed secondary assessment. This is a head-to-toe examination to identify less critical injuries or conditions.

- SAMPLE History:

- S: Signs/Symptoms

- A: Allergies

- M: Medications

- P: Past medical history

- L: Last meal/oral intake

- E: Events leading to the injury/illness

- Head-to-toe Physical Examination:

- Head/Neck: Look for signs of trauma (bruising, swelling, deformities), pupillary response, and airway patency.

- Chest: Assess for equal chest rise, breath sounds, and any signs of injury.

- Abdomen: Palpate for tenderness, rigidity, or distension.

- Extremities: Assess for fractures, dislocations, and neurovascular status (pulses, capillary refill, sensation).

- Back: Log-roll the child to inspect the spine for signs of injury, especially if a spinal injury is suspected.

Obstructed Airway

- Incidence: Obstructed airway is a leading cause of death and disability in children, particularly those under 3 years of age.

- Etiology: Common causes include foreign body aspiration (e.g., small toys, buttons, coins, food like hot dogs, carrots, candies, or grapes), infections (e.g., croup, epiglottitis), and trauma.

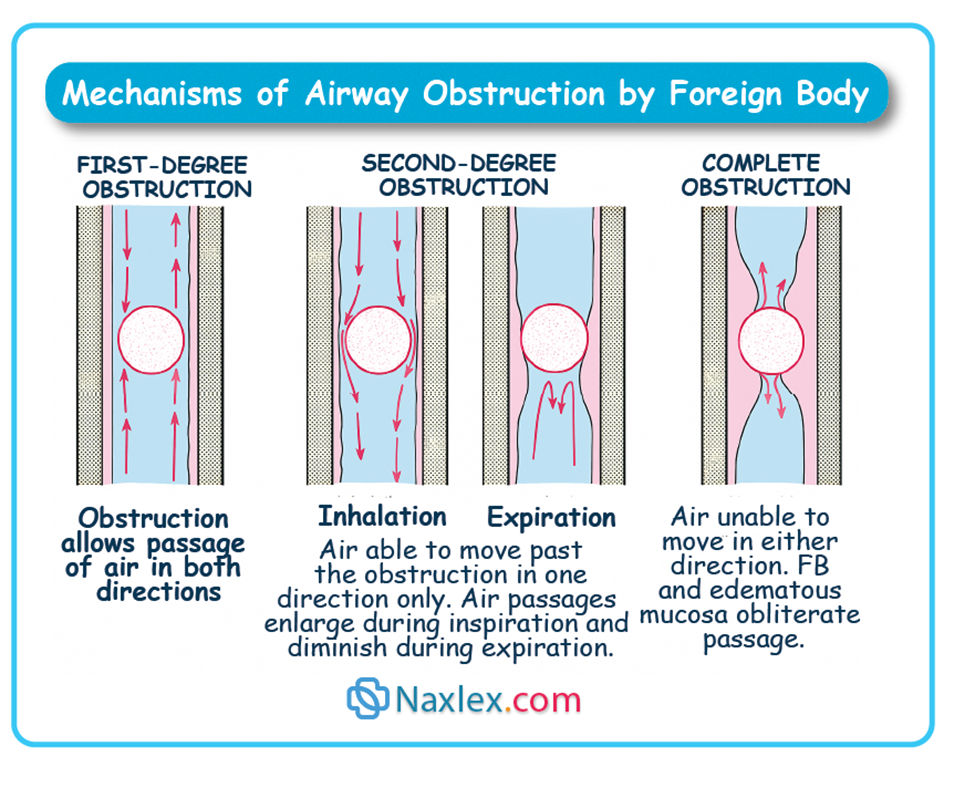

- Pathophysiology: An obstructed airway prevents adequate oxygen exchange. This leads to hypoxemia (low oxygen in the blood) and hypercapnia (high carbon dioxide). If not corrected, this rapidly progresses to respiratory arrest, cardiac arrest, and anoxic brain injury.

- Diagnosis: Diagnosis is based on a rapid assessment of the child's symptoms.

- Mild/first-degree Obstruction: Child is conscious, able to cough, and may have wheezing between coughs. Do not interfere with their cough, as this is the most effective way to clear the obstruction.

- Moderate/second-degree Obstruction: Th e conscious child will appear frightened and panicky with inspiratory stridor and ineffective cough, little to no air exchange. They may also wrap his or her hands around his or her own throat to indicate the presence of an obstruction.

-

- Severe/complete Obstruction: Child is unable to speak or cough, has silent coughs, or is making high-pitched sounds (stridor). They may be cyanotic (blue) and become unresponsive.

- Treatment:

A. Mild Obstruction: Unless the obstruction should worsen, emotional support should be provided while the child coughs up the obstruction.

B. Moderate to severe obstructions:

-

- Conscious Infant (under 1 year) with Moderate to Severe Obstruction: Perform a combination of 5 back blows and 5 chest thrusts until the obstruction is cleared or the infant becomes unresponsive.

-

- Conscious Child (over 1 year)/Adolescent with Moderate to Severe Obstruction: Perform the Heimlich maneuver (abdominal thrusts).

-

- Unconscious Child/Adolescent: Begin CPR. After each set of compressions, check the mouth for a foreign object and remove it if visible. Do not perform blind finger sweeps.

- The child may require bronchoscopy or laryngoscopy for removal of the object.

- Nursing Considerations/Diagnoses:

- Nursing Diagnoses:

- Ineffective Airway Clearance related to foreign body aspiration.

- Impaired Gas Exchange.

- Risk for injury/Deficient knowledge: Parents must be educated regarding safety precautions to take in order to prevent airway obstructions. Parents should be strongly encouraged to become certified in CPR and other first aid skills.

- Grieving/Risk for Complicated Grieving: If the child dies.

- Interventions:

- Rapidly assess the level of obstruction.

- Perform age-appropriate maneuvers to dislodge the foreign body.

- Provide supplemental oxygen.

- Prepare for intubation if other measures fail.

- Provide psychological support to the child and family.

- Nursing Diagnoses:

Shock

- Incidence: Shock is a common and often underestimated cause of death in children. It can progress rapidly and is often a result of an underlying condition.

- Etiology:

- Hypovolemic Shock: Most common type in children, often caused by dehydration from vomiting, diarrhea, or burns. It is also caused by extensive loss of blood.

- Distributive Shock: Caused by widespread vasodilation, often seen in sepsis from micro-organisms such as Escherichia coli, Streptococcus pyogenes (group A strep), and Neisseria meningitides. It may also be caused anaphylaxis or drug overdose.

- Cardiogenic Shock: Caused by severe injury to the heart muscle, for instance, due to heart failure.

- Obstructive Shock: Caused by a physical obstruction of blood flow (e.g., tension pneumothorax, cardiac tamponade).

- Pathophysiology: Shock is a state of inadequate tissue perfusion and oxygen delivery to meet metabolic demands. Children have a remarkable ability to compensate for early shock by increasing heart rate and systemic vascular resistance. This compensatory phase can be deceptive, as it may mask the severity of the condition. As shock progresses, compensatory mechanisms fail, leading to hypotension (a late and ominous sign), organ dysfunction, and multi-organ failure.

- Signs and symptoms:

- Initial Signs (Compensated Shock): Tachycardia (most common and earliest sign), tachypnea, weak peripheral pulses, cool extremities, prolonged capillary refill time (>2 seconds), and decreased urine output.

- Late Signs (Decompensated Shock): Hypotension, altered mental status, apnea, and weak or absent central pulses.

- Diagnosis: Early diagnosis is critical. Clinical picture in conjunction with X-rays and a variety of laboratory data, including blood cultures, complete blood counts (CBC), lumbar puncture, blood gases, and serum electrolytes.

- Treatment:

- Initial Management: Administer 100% oxygen and establish IV or intraosseous (IO) access.

- Fluid Resuscitation: Administer a rapid bolus of 20 mL/kg of an isotonic crystalloid (e.g., normal saline or lactated Ringer's) over 5-10 minutes. This may be repeated up to three times.

- Vasopressors: If hypotension persists after fluid resuscitation, vasopressors (e.g., dopamine, norepinephrine) may be initiated.

- Treat the Underlying Cause: Treat the cause of the shock, whether it's infection (antibiotics), hemorrhage (blood products), or an allergic reaction (epinephrine).

- Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO): This is a is a life-support system that acts as an artificial heart and/or lungs. It's used for patients with severe heart or lung failure that can't be treated with conventional methods, such as a mechanical ventilator. It is a treatment similar to cardiopulmonary bypass, usually only used as treatment for infants and young children. Its primary purpose is to give the patient's heart and lungs time to rest and heal. It doesn't cure the underlying disease.

- Nursing Considerations/Diagnoses:

- Nursing Diagnoses:

- Risk for Ineffective Tissue Perfusion related to decreased circulating volume.

- Risk for Ineffective Airway Clearance.

- Risk for Decreased Cardiac Output.

- Risk for Deficient Fluid Volume: Administer prescribed IV fluids.

- Risk for Altered Coping/Anxiety: Calmly provide the child and parents with information regarding care, employing simple and concise language; provide opportunities for the child and parents to express fears and concerns; refer the family to social services as needed; assist the family to identify support systems and coping strategies.

- If the child dies, Grieving/Risk for Complicated Grieving: Provide the parents and others, if appropriate, with the opportunity to express their feelings; allow the parents, if appropriate, time to be with and to say good-bye to their child; educate the parents regarding the 5 stages of grief.

- Interventions:

- Continuous monitoring of vital signs, including heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation.

- Assess capillary refill time and skin temperature frequently.

- Monitor urine output (a key indicator of renal perfusion).

- Administer prescribed fluids and medications.

- Maintain a calm environment to reduce stress and metabolic demands.

- Nursing Diagnoses:

Trauma

- Incidence: Trauma is the leading cause of death in children and adolescents. Motor vehicle accidents (when the child is a passenger in the car or when the child is a pedestrian), falls, gun trauma, and child abuse are common etiologies.

- Etiology:

- Blunt Trauma: Most common in children.

- Penetrating Trauma: Less common but often more severe.

- Pathophysiology:

- Children's unique anatomy makes them more vulnerable to severe trauma. Their larger head-to-body ratio increases the risk of head injuries. Their abdominal organs are less protected by muscle and fat, making them susceptible to blunt force injury. Their more pliable bones are more prone to "greenstick" fractures.

- Waddell’s triad, refers to the traumatic injuries sustained by pedestrian children who are hit by a car. The children are injured in three distinctly serious ways:

i. Abdominal injuries that occur during the initial strike.

ii. Injuries to the extremities that occur when the child lands on the ground after being thrown through the air.

iii. Head injuries that occur when the child lands on his or her head after being thrown through the air. Because children’s heads are often the heaviest parts of their bodies, their heads frequently sustain serious injury.

- Diagnosis:

- Clinical picture in conjunction with X-rays and a variety of laboratory data including blood cultures, CBCs, lumbar puncture, blood gases, and serum electrolytes.

- Primary Survey (ABCDEs):

- Airway with cervical spine protection

- Breathing and ventilation

- Circulation with hemorrhage control

- Disability (neurologic status)

- Exposure (completely undress the child to examine for injuries)

- Secondary Survey: A more detailed head-to-toe examination.

- Treatment:

- Stabilization: Maintain a patent airway and provide oxygen. Control any external bleeding.

- Immobilization: Immobilize the cervical spine until cleared.

- Fluid Resuscitation: Administer isotonic fluids for hypovolemic shock.

- Surgical Intervention: For internal bleeding or organ damage.

- Prevention:

- The parents and child must be educated regarding car and pedestrian safety practices

- Infants and young children should be supervised whenever on elevated surfaces.

- All firearms and ammunition should be kept in separate, locked safes.

- Nursing Considerations/Diagnoses:

- Nursing Diagnosis:

- Risk for Ineffective Tissue Perfusion related to hemorrhage.

- Deficient knowledge: Parents must be educated regarding safety precautions to take to prevent traumatic injury. Parents should be encouraged to become certified in CPR and other first aid skills.

- Risk for Impaired Gas Exchange: Assist with intubation, as needed, administer oxygen, as needed, carefully monitor vital signs

- Risk for Deficient Fluid Volume: Administer IV therapy, as ordered, maintain strict intake and output.

- Risk for Infection: Employing the five rights of medication administration, administer safe dosages of antibiotics/antivirals/antifungals, as prescribed.

- Risk for Altered Coping/Anxiety: calmly provide the child and parents with information regarding trauma care, employing simple and concise language. Provide opportunities for the child and parents to express fears, concerns, and guilt. Refer the family as needed to social services.

- Risk for Altered Parenting: Depending on the source of the injury/emergency, and if applicable, the nurse should notify child protective services of child abuse or child neglect.

- If the child dies, Grieving/Risk for Complicated Grieving.

- Interventions:

- Maintain cervical spine immobilization.

- Monitor for signs of hemorrhage (tachycardia, hypotension).

- Maintain body temperature to prevent hypothermia.

- Administer pain management.

- Be vigilant for signs of child abuse, especially in cases where the history does not match the injury.

- Nursing Diagnosis:

Acute Poisonings

- Incidence: Poisonings are a major cause of pediatric emergencies. Most are unintentional and occur in toddlers and preschoolers. Intentional poisoning (i.e., from the ingestion of alcohol and/or prescription medications) most commonly is seen in the adolescent population.

- Etiology:

- Medication ingestion: Tylenol (acetaminophen), aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid), and vitamins are the most common poisons in toddlers and preschoolers. Prescription medications (e.g., analgesics, narcotics, antidepressants, antianxiety medications, as well as illicit drugs) often are purposefully ingested by older school-age and adolescent children.

- Other poisons that may be ingested: Cleaning products, gasoline, and kerosene most commonly are ingested by toddlers and preschoolers. Alcohol most commonly is ingested by older school-age and adolescent children. Poisons may also be “ingested” via the respiratory system in the form of a gas or aerated particles or via the skin in the form of a topical substance.

- Pathophysiology:

The effects of poisoning depend on the substance ingested, the dose, and the child's body weight. Children have a higher metabolic rate and a smaller body mass, making them more susceptible to the toxic effects of substances.

-

- Acetaminophen: Ingestion of greater than 150 mg/kg is considered toxic. Therapeutic dose is 10 to 15 mg/kg every 6 to 8 hr. Hepatotoxicity can develop from the physiological metabolism of the medication.

- Signs and symptoms depend on the quantity ingested. Initially, nausea and vomiting and flu-like symptoms. After 24 hours, elevated liver enzymes, elevated bilirubin, and right upper quadrant pain. In 3 to 7 days, the child may develop liver failure. After 1 week, either the child will recover or the child’s health will deteriorate further.

- Acetaminophen: Ingestion of greater than 150 mg/kg is considered toxic. Therapeutic dose is 10 to 15 mg/kg every 6 to 8 hr. Hepatotoxicity can develop from the physiological metabolism of the medication.

-

- Aspirin: Ingestion of greater than 150 mg/kg is considered toxic. Therapeutic dose is 10 to 15 mg/kg every 4 to 6 hr. Many organ systems may be adversely affected. Initially, the child will exhibit respiratory alkalosis in an attempt to compensate for the ingestion. The alkalosis quickly shifts to metabolic acidosis with hypokalemia and dehydration when the salicylic acidemia overwhelms the compensatory response.

- Signs and symptoms: Initially, nausea and vomiting with hyperpnea, followed by central nervous system changes (i.e., confusion, seizures, coma), renal failure, bleeding, hyponatremia, hypokalemia, hypoglycemia, dehydration, tinnitus or deafness.

- Aspirin: Ingestion of greater than 150 mg/kg is considered toxic. Therapeutic dose is 10 to 15 mg/kg every 4 to 6 hr. Many organ systems may be adversely affected. Initially, the child will exhibit respiratory alkalosis in an attempt to compensate for the ingestion. The alkalosis quickly shifts to metabolic acidosis with hypokalemia and dehydration when the salicylic acidemia overwhelms the compensatory response.

-

- Cleaning supplies, gasoline, and other such substances: Severe damage to the mouth, esophagus, and stomach, respiratory compromise, and blood chemistry disruptions.

- Alcohol: a physiological depressant.

- Signs and symptoms: Confusion, vomiting, stupor, and respiratory compromise.

- Diagnosis:

- History: The most important tool is a detailed history, including the substance, amount, and time of ingestion.

- Physical Examination: Look for signs and symptoms consistent with the suspected poison (e.g., pinpoint pupils with opioids, dry/red skin with anticholinergics).

- Toxicology Screen: Blood and urine tests can identify the substance.

- Treatment:

- Immediate care at the scene.

- Assess the child: The child must be assessed for responsiveness and for the need of emergency intervention. The child’s immediate, physiological needs must be met.

- Terminate the exposure: depending on the situation, for the safety of the child and/or the nurse, this action may take precedence over the assessment of the child. If possible, exposure to the poison should be terminated.