Please set your exam date

Fluids and Electrolytes & Acid-Base Balance

Study Questions

Practice Exercise 1

Plasma, the liquid constituent of blood, is correctly identified as which of the following?

Explanation

Body fluids are organized into compartments: intracellular fluid (inside cells), extracellular fluid (outside cells) - which itself is divided into interstitial fluid (between cells) and the intravascular compartment (blood plasma).

Rationale for correct answer:

2. Intravascular fluid: Plasma is the liquid portion of blood that remains when cells are removed; it occupies the vascular (intravascular) compartment and carries proteins, clotting factors, electrolytes, nutrients, and hormones.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Interstitial fluid: Interstitial fluid is the ECF that surrounds cells (fluid in tissue spaces). It is outside the blood vessels; plasma is inside the blood vessels.

3. Intracellular fluid: Intracellular fluid is the fluid inside cells (largest compartment). Plasma is extracellular and intravascular, not intracellular.

4. 40% of total body fluid: Rough approximations: total body water ≈ 60% of body weight; intracellular ≈ 2/3 of TBW, extracellular ≈ 1/3. Plasma is only a portion of the ECF (about ~5% of body weight, roughly 20–25% of the ECF), not 40% of TBW.

Take home points

- Plasma = intravascular (the fluid inside blood vessels); interstitial fluid = ECF outside vessels; intracellular = inside cells.

- Remember relative volumes: intracellular ≈ two-thirds of TBW, extracellular ≈ one-third; plasma is only a small fraction of TBW but is critical for perfusion and transport.

The movement of the solvent water from an area of lesser solute concentration to an area of greater solute concentration until equilibrium is established is known as:

Explanation

Transport across cell membranes occurs by several mechanisms. Some move solvent (water) and some move solutes (ions, molecules). Understanding the difference between passive processes (no ATP) and active processes (require ATP), and between movement of water versus movement of dissolved particles, is essential for predicting how cells respond to changes in their environment

Rationale for correct answer:

1. Osmosis is the passive movement of water (solvent) across a semipermeable membrane from an area of lower solute concentration (higher water concentration) to an area of higher solute concentration (lower water concentration) until equilibrium is reached.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

2. Diffusion is the passive movement of solute particles from an area of higher concentration to an area of lower concentration (down their concentration gradient). It refers to solute movement, not solvent movement specifically.

3. Active transport moves substances against their concentration gradient and requires energy (ATP) - e.g., the Na⁺/K⁺ pump. It’s not the passive movement of water from low to high solute concentration.

4. Filtration is movement of fluid and solutes across a membrane driven by hydrostatic pressure (for example, blood pressure forcing plasma across glomerular membranes). It’s pressure-driven, not osmosis.

Take home points

- Osmosis = water moves toward the higher solute concentration across a semipermeable membrane.

- Distinguish osmosis (water) from diffusion (solute) and from pressure-driven filtration or energy-dependent active transport.

Potassium functions as which of the following?

Explanation

Electrolytes are distributed differently between compartments and each has a “major” role: sodium predominates in the extracellular fluid and potassium predominates intracellularly. These distributions are essential for resting membrane potential, nerve and muscle function, and cardiac conduction.

Rationale for correct answer:

3. The major cation of intracellular fluid: Potassium (K⁺) is the principal positive ion inside cells and is crucial for maintaining resting membrane potential, muscle contraction, and cardiac rhythm.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. The chief electrolyte of extracellular fluid: Sodium (Na⁺) is the chief extracellular electrolyte/cation, not potassium.

2. The most abundant electrolyte in the body: Potassium is the major intracellular cation and, by total body content (because the intracellular compartment is large), potassium is present in large amounts

4. The chief extracellular anion: Chloride (Cl⁻) is the chief extracellular anion; potassium is a cation and is primarily intracellular.

Take home points

- Potassium is the principal intracellular cation- vital for resting membrane potential, skeletal and cardiac muscle function.

- Potassium balance is tightly regulated by the kidneys and by shifts (insulin, acid–base changes); small serum changes can produce large effect.

Which of the following would the nurse use as the most reliable indicator of a patient’s fluid balance status?

Explanation

Accurate assessment of a patient’s fluid status is critical for safe nursing care (managing IV fluids, diuretics, heart failure, dehydration). Clinicians use multiple data points (intake/output, exam findings, labs), but some measures are more sensitive and reproducible than others.

Rationale for correct answer:

4. Daily weights (same scale, same time of day, same clothing/blanket conditions) are the most reliable and objective method to detect small changes in total body water - roughly 1 kg (2.2 lb) ≈ 1 L of fluid change.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Intake and output: I&O monitoring is important, but it’s subject to recording errors, misses insensible losses (sweat, respiration), and doesn’t account for fluid shifts between compartments. It’s helpful trend data but less precise than weight.

2. Skin turgor: Skin turgor can be affected by age, nutrition, and skin elasticity; it’s a supportive physical sign but insensitive for small changes in total body fluid.

3. Complete blood count: Hematocrit/hemoglobin can reflect hemoconcentration or hemodilution but are influenced by bleeding, anemia, transfusion, and other factors; they’re not the best single indicator of fluid balance.

Take home points

- Use daily weights as the primary objective measure of fluid status; weigh at the same time each day, on the same scale, with consistent clothing/linens for accuracy.

- Combine daily weights with I&O, vital signs, exam findings, and labs for full clinical context - but trust the daily weight for detecting true net fluid gain/loss.

A client is admitted to the hospital for hypocalcemia. Nursing interventions relating to which system would have the highest priority?

Explanation

Calcium is essential for cardiac contractility and conduction, neuromuscular excitability, and bone metabolism. Severe hypocalcemia can produce life-threatening cardiac effects (prolonged QT, arrhythmias, decreased contractility) in addition to neuromuscular signs such as tetany and paresthesias.

Rationale for correct answer:

2. Cardiac: Calcium is critical to myocardial contraction and electrical conduction. Hypocalcemia may prolong the QT interval and predispose to dangerous arrhythmias or impaired contractility; therefore continuous cardiac monitoring and rapid correction (when indicated) are top priorities.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Renal: The kidneys participate in calcium balance (via reabsorption and vitamin D activation), but immediate nursing interventions for hypocalcemia are less often renal-directed. Renal issues are important for long-term calcium management but are not the highest acute priority.

3. Gastrointestinal: GI symptoms (nausea, abdominal cramps) can occur with electrolyte disturbances, but they are not the most urgent systems to monitor for acute hypocalcemic complications.

4. Neuromuscular: Hypocalcemia commonly causes paresthesias, muscle cramps, tetany, and positive Chvostek/Trousseau signs. These are important and potentially severe (e.g., laryngospasm), but cardiac complications take precedent because they are immediately life-threatening.

Take home points

Always place a patient with significant hypocalcemia on continuous cardiac monitoring and watch for QT prolongation and arrhythmias.

Treat symptomatic/severe hypocalcemia promptly:

- IV calcium per protocols

- Correct contributing factors (low magnesium, vit D deficiency)

- Monitor IV sites and vital signs during calcium administration.

Practice Exercise 2

An older nursing home resident has refused to eat or drink for several days and is admitted to the hospital. The nurse should expect which assessment finding?

Explanation

After several days without food or fluids, an older adult is at high risk for hypovolemia (dehydration). Age-related blunted thirst, comorbidities, and medications make them especially vulnerable. Classic findings reflect reduced circulating volume and compensatory sympathetic responses.

Rationale for correct answer:

2. Weak, rapid pulse: Tachycardia is a compensatory response to low stroke volume; the pulse feels weak (thready) due to reduced preload.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Increased blood pressure: With decreased intravascular volume, BP typically falls (or shows orthostatic drops). Hypertension would not be expected unless there’s another cause.

3. Moist mucous membranes: Dehydration causes dry, sticky mucous membranes and often a coated tongue.

4. Jugular vein distention: Hypovolemia produces flat/collapsed neck veins; JVD suggests fluid overload or right-sided heart issues, not dehydration.

Take home points:

In dehydration, expect:

- Tachycardia

- hypotension/orthostasis

- dry mucosa

- poor skin turgor

- concentrated urine (often with ↑ BUN/Cr ratio and ↑ serum osmolality).

The intake and output (I&O) record of a client with a nasogastric tube who has been attached to suction for 2 days shows greater output than input. Which nursing diagnoses are most applicable? Select all that apply

Explanation

Prolonged nasogastric suction removes fluid and electrolytes, often causing actual fluid volume deficit and dry mucous membranes.

Rationale for correct answer:

1. Deficient Fluid Volume: Negative I&O over 2 days with GI suction results in actual hypovolemia.

3. Impaired Oral Mucous Membranes: NPO/NG suction commonly cause dry, irritated oral mucosa.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

2. Risk for Deficient Fluid Volume: “Risk for” is used when a problem hasn’t occurred yet; here the deficit is present.

4. Impaired Gas Exchange: No evidence of oxygenation/ventilation issues provided.

5. Decreased Cardiac Output: Could occur with severe hypovolemia, but no VS or perfusion findings provided.

Take home points

- Use actual vs risk correctly: negative I&O from NG suction = Deficient Fluid Volume (not “Risk for”).

- NG suction commonly causes dry oral mucosa; include oral care and humidification in the plan.

Which client statement indicates a need for further teaching regarding treatment for hypokalemia?

Explanation

Hypokalemia, defined as a serum potassium level below 3.5 mEq/L, can result from excessive potassium loss (e.g., diuretics, GI losses) or inadequate intake. Treatment focuses on replacing potassium and addressing the underlying cause.

Rationale for correct answer:

4. “I will stop using my salt substitute.” Most salt substitutes are made with potassium chloride, which can actually help correct hypokalemia. Stopping the use of salt substitutes would decrease potassium intake and worsen hypokalemia.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. “I will use avocado in my salads.” Avocados are rich in potassium and are an appropriate dietary choice for someone with hypokalemia. This statement reflects correct understanding of incorporating potassium-rich foods.

2. “I will be sure to check my heart rate before I take my digoxin.” Hypokalemia increases sensitivity to digoxin, putting the client at risk for digoxin toxicity, which manifests as bradycardia, nausea, and visual disturbances. Checking the heart rate before taking digoxin is an essential safety practice.

3. “I will take my potassium in the morning after eating breakfast.” Potassium supplements can irritate the gastrointestinal tract, so they should be taken with food or after meals to reduce GI upset. Taking them in the morning after breakfast is appropriate.

Take home points

- Hypokalemia can be corrected through both dietary intake (bananas, oranges, avocados, potatoes) and supplements.

- Clients on digoxin should be carefully monitored because hypokalemia increases the risk of digoxin toxicity.

An older man is admitted to the medical unit with a diagnosis of dehydration. Which sign or symptom is most representative of a sodium imbalance?

Explanation

Sodium is the primary extracellular electrolyte and a major determinant of serum osmolality and fluid distribution between body compartments. Changes in sodium (either high or low) most commonly affect the central nervous system because shifts in osmolality cause neuronal swelling or shrinkage.

Rationale for correct answer:

2. Mental confusion: Sodium disturbances (both hyponatremia and hypernatremia) cause changes in neuronal cell volume and cerebral function, so altered mental status/confusion is a hallmark sign.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Hyperreflexia: More typically associated with disorders that increase neuromuscular excitability (for example, hypocalcemia or hypomagnesemia). It is not a classic or specific sign of sodium imbalance.

3. Irregular pulse: Cardiac rhythm disturbances are most classically linked to potassium abnormalities (hyper- or hypokalemia). Sodium imbalance is less likely to present primarily as an irregular pulse.

4. Muscle weakness: Can occur with several electrolyte problems (notably potassium disorders). Severe hypernatremia may cause weakness, but muscle weakness is a less specific/typical sign of sodium imbalance than CNS changes like confusion.

Take home points:

- Altered mental status is the most sensitive and common clinical clue to a clinically significant sodium imbalance.

- Always check serum sodium and assess volume status when an older patient presents with new-onset confusion.

- Correct sodium disturbances carefully to avoid rapid shifts.

- Risk of central pontine myelinolysis with overly rapid correction of chronic hyponatremia.

Which of the following is the most common etiologic factor related to the nursing diagnosis of Excess Fluid Volume?

Explanation

Excess Fluid Volume (fluid overload) occurs when there is too much fluid in the intravascular and/or interstitial spaces. Common causes include excessive IV fluid administration, heart failure, renal failure, and conditions that increase fluid retention.

Rationale for correct answer:

3. Excessive IV infusion: Administering IV fluids too rapidly or in inappropriate amounts is a common iatrogenic cause of fluid volume excess, especially in patients with impaired cardiac or renal function who cannot handle the added load.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Increased need for fluids secondary to fever: Fever increases insensible losses and fluid need; if anything, fever predisposes to deficit, not excess.

2. Abnormal fluid loss from vomiting: Vomiting causes fluid loss and dehydration, not excess volume.

4. Decreased fluid intake secondary to depression: Decreased intake produces deficit, not excess.

Take home points

- The most preventable cause of excess fluid volume in hospitalized patients is excessive IV infusion (rate or volume).

- Always verify orders, titrate carefully, and consider patient comorbidities (HF, renal failure).

- Monitor for early signs of fluid overload: daily weights, I&O, peripheral edema, crackles on lung auscultation, increased JVD, rising BP - intervene early to prevent pulmonary edema.

Practice Exercise 3

An older client comes to the emergency department experiencing chest pain and shortness of breath. An arterial blood gas is ordered. Which of the following ABG results indicates respiratory acidosis?

Explanation

In acid-base pattern recognition use ROME: Respiratory Opposite (pH and PaCO₂ move opposite), Metabolic Equal (pH and HCO₃⁻ move together). Respiratory acidosis = low pH, high PaCO₂ (with normal/high HCO₃⁻ if compensation).

Rationale for correct answer:

2. pH 7.32; PaCO₂ 46; HCO₃⁻ 24: Respiratory acidosis (acute): low pH with elevated PaCO₂; HCO₃⁻ normal (no or minimal compensation).

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. pH 7.54; PaCO₂ 28; HCO₃⁻ 22: Respiratory alkalosis (high pH, low PaCO₂).

3. pH 7.31; PaCO₂ 35; HCO₃⁻ 20: Metabolic acidosis: low pH with low HCO₃⁻; PaCO₂ not elevated.

4. pH 7.50; PaCO₂ 37; HCO₃⁻ 28: Metabolic alkalosis: high pH with elevated HCO₃⁻ and near-normal PaCO₂.

Take home points:

- Respiratory acidosis = ↓pH with ↑PaCO₂; think hypoventilation.

- Use ROME: Respiratory (Opposite), Metabolic (Equal); check pH first, then PaCO₂/HCO₃⁻ to classify and assess compensation.

The client’s arterial blood gas results are pH 7.32; PaCO₂ 58; HCO₃⁻ 32. The nurse knows that the client is experiencing which acid–base imbalance?

Explanation

Arterial blood gas interpretation uses three key values: pH (acidemia vs alkalemia), PaCO₂ (respiratory component- high CO₂- respiratory acidosis), and HCO₃⁻ (metabolic component- low HCO₃⁻ -metabolic acidosis).

Rationale for correct answer:

2. Respiratory acidosis: The pH is acidic and PaCO₂ is markedly elevated (58 mmHg - hypoventilation), indicating a primary respiratory acidosis. The HCO₃⁻ is elevated, reflecting renal (metabolic) compensation.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Metabolic acidosis: In metabolic acidosis you would expect low HCO₃⁻ (not high). Here HCO₃⁻ is elevated, so metabolic acidosis is not the primary problem.

3. Metabolic alkalosis: Would present with an elevated pH and elevated HCO₃⁻. Here pH is low, so not metabolic alkalosis.

4. Respiratory alkalosis: Would present with low PaCO₂ and alkalemia (high pH). This ABG shows the opposite (high PaCO₂ and acidemia), so it’s not respiratory alkalosis.

Take home points:

- Interpret ABGs in order: pH → PaCO₂ → HCO₃⁻. If pH is acidotic and PaCO₂ is high, the primary process is respiratory acidosis.

- Respiratory acidosis results from hypoventilation (e.g., COPD exacerbation, respiratory depression from drugs, neuromuscular failure).

- Treatment focuses on improving ventilation and addressing the underlying cause; monitor for compensation and oxygenation.

Which acid–base imbalance would the nurse suspect after assessing the following arterial blood gas values (pH, 7.30; PaCO₂, 36 mm Hg; HCO3-, 14 mEq/L)?

Explanation

Arterial blood gas (ABG) interpretation is a core nursing skill for assessing acid-base balance.

Rationale for correct answer:

3. Metabolic acidosis: Low pH (acidemia) with low HCO₃⁻ = metabolic acidosis. PaCO₂ is normal, so there’s no respiratory compensation yet.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Respiratory acidosis: Would show low pH with high PaCO₂. Here PaCO₂ is normal, so not respiratory acidosis.

2. Respiratory alkalosis: Would show high pH with low PaCO₂. Here the pH is low and HCO₃⁻ is abnormal, so not respiratory alkalosis.

4. Metabolic alkalosis: Would show high pH and high HCO₃⁻, which is the opposite of this ABG.

Take home points

- Always check whether PaCO₂ and HCO₃⁻ are moving in the same or opposite direction as the pH to identify the primary disturbance.

The nurse alertly assesses the acid–base balance of a patient because she is aware that the patient will be unable to effectively control his carbonic acid supply. This is most likely a patient with bad damage to which of the following?

Explanation

Acid-base balance is maintained mainly by the lungs (regulate carbonic acid via CO₂ exhalation) and the kidneys (regulate bicarbonate via HCO₃⁻ reabsorption/production).

Rationale for correct answer:

2. Lungs: The lungs control CO₂ elimination (CO₂ + H₂O ↔ H₂CO₃). Impaired ventilation or lung damage prevents effective removal of CO₂, altering the carbonic acid component and causing respiratory acid–base disturbances.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Kidneys regulate the metabolic component (bicarbonate HCO₃⁻) and excrete or retain H⁺ and HCO₃⁻; they do not directly control CO₂ (carbonic acid) removal.

3. Adrenal glands influence electrolyte and volume status (aldosterone) and can indirectly affect acid–base balance, but they are not the primary controllers of carbonic acid/CO₂.

4. Blood vessels transport gases and acids but do not control CO₂ elimination; impaired vasculature alone would not be described as inability to control carbonic acid supply.

Take home points

- The lungs regulate the respiratory/CO₂ (carbonic acid) component of acid–base balance; impaired ventilation → respiratory acidosis (CO₂ retention) or alkalosis (hyperventilation).

- When ABGs show an abnormal CO₂ (PaCO₂) causing pH changes, think lung (respiratory) pathology first; when HCO₃⁻ is primary abnormality, think kidney (metabolic) causes.

Which assessment finding would lead the nurse to suspect that a patient’s IV has infiltrated?

Explanation

Infiltration occurs when IV fluid leaks from the vein into the surrounding tissues. It produces local changes at the site (temperature, color, swelling, pain, flow changes) that help you distinguish it from other IV complications (phlebitis, infection, occlusion).

Rationale for correct answer:

4. The site is pale, cool, swollen, and painful: Infiltration typically causes pallor, coolness at the site (because fluid is in tissue, not in blood flow), swelling, and sometimes pain or discomfort.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. In the past hour, only 50 mL of fluid has infused: Slow or reduced infusion rate is nonspecific - could indicate an occlusion, a kinking of the tubing, an air or pressure issue, or infiltration, but by itself it is not the most characteristic sign of infiltration.

2. The insertion site is red, hot, and swollen: Redness and warmth are classic for phlebitis (inflammation of the vein) or local infection, not infiltration. Phlebitis tends to be tender along the course of the vein.

3. The patient’s temperature has risen to 101°F (38.3°C). A fever suggests systemic infection or catheter-related bacteremia - a serious sign but not the characteristic local finding of infiltration.

Take-home points

Inspect and palpate IV sites frequently; look for pallor, coolness, swelling, and pain - these are classic for infiltration.

If infiltration is suspected:

- stop the infusion

- remove the cannula

- elevate the extremity

- follow facility protocol for management and documentation (and notify provider if vesicant or large volume).

Comprehensive Questions

A man brings his elderly wife to the emergency department. He states that she has been vomiting and has had diarrhea for the past 2 days. She appears lethargic and is complaining of leg cramps. What should the nurse do first?

Explanation

In hypovolemia and electrolyte loss (especially potassium) from GI losses, first actions should stabilize circulation and create access for rapid treatment and labs.

Rationale for correct answer:

1. Start an IV: Establishes access for rapid fluid resuscitation and lab draws, addressing immediate circulation risk and enabling antiemetics/electrolytes to be given IV.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

2. Review the results of serum electrolytes: Results aren’t available yet; delaying access/treatment for labs risks worsening hypovolemia. Draw labs after IV access is obtained.

3. Offer the woman foods high in sodium and potassium: Not appropriate in an actively vomiting, lethargic patient; risk of aspiration and likely intolerance. Electrolytes should be replaced parenterally initially.

4. Administer an antiemetic: Helpful, but you need IV access to give it promptly and fluids are the higher priority for stabilization.

Take home points

- In hypovolemia, think ABCs → IV access → fluids → labs/meds.

- GI losses often cause volume depletion and electrolyte deficits; correct both, but stabilize circulation first.

The nurse would assess for signs of hypomagnesemia in which of the following clients? Select all that apply

Explanation

Magnesium is an important intracellular cation involved in neuromuscular function, cardiac conduction, and many enzymatic reactions. Hypomagnesemia commonly results from inadequate intake, gastrointestinal losses (vomiting, diarrhea, prolonged nasogastric suction), malabsorption, chronic alcoholism, and some critical illnesses (including pancreatitis).

Rationale for correct answer:

2. A client with pancreatitis: Both acute and chronic pancreatitis are associated with magnesium depletion (malabsorption in chronic disease; saponification of cations in necrotic fat in acute pancreatitis), so patients with pancreatitis are at risk for hypomagnesemia.

4. A client with excessive nasogastric drainage: Prolonged NG suctioning or other GI losses (vomiting, diarrhea) can cause significant magnesium depletion.

5. A client with chronic alcoholism: Chronic alcohol use is one of the most common causes of hypomagnesemia because of poor intake, GI losses, and increased renal excretion.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. A client with renal failure: Not typically associated with hypomagnesemia. Renal failure usually decreases magnesium excretion and therefore predisposes to hypermagnesemia, not hypomagnesemia, unless the patient has other complicating factors.

3. A client taking magnesium-containing antacids: Magnesium-containing antacids tend to increase magnesium load (and can cause hypermagnesemia, especially if renal function is impaired). They are not a classic cause of hypomagnesemia.

Take home points:

- Recognize common risk settings for hypomagnesemia.

- Suspect low magnesium when neuromuscular irritability, refractory hypokalemia, or cardiac arrhythmias occur.

- Monitor electrolytes (Mg²⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺), ECG, and replace magnesium per protocol.

A patient has been encouraged to increase her fluid intake. Which measure would be most effective for the nurse to implement?

Explanation

Adequate hydration supports renal function, tissue perfusion, and homeostasis. Nurses play a key role in promoting fluid intake, especially for clients at risk of dehydration. The most effective interventions are practical, patient-centered strategies that increase actual fluid consumption, rather than abstract teaching.

Rationale for correct answer:

2. Keeping fluids readily available for the patient: Accessibility is the most effective measure because it promotes actual drinking behavior. Fluids placed within reach make adherence easier.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1.Explaining the mechanisms involved in transporting fluids: This provides knowledge but doesn’t directly improve fluid intake. Education alone may not translate into behavior.

3. Emphasizing long-term outcomes: Future benefits may not motivate immediate intake. Patients are more likely to respond to short-term, practical actions.

4. Planning to offer most fluids in the evening: Ineffective and potentially problematic. Concentrating fluids late in the day increases nocturia and risk of disturbed sleep/falls, especially in older adults.

Take home points

- The best nursing interventions are often the simplest: keep fluids within reach, offer them frequently, and individualize to patient preference.

- Avoid strategies that increase nighttime urination (like giving most fluids in the evening), especially for older patients at fall risk.

Which of the following would the nurse need to keep in mind when preparing to assist the physician with insertion of a nontunneled percutaneous central venous catheter?

Explanation

Central venous catheters come in several types (nontunneled short-term CVCs, tunneled CVCs, implanted ports, PICCs, femoral lines) and are used for central venous access for fluids, medications, hemodynamic monitoring, and blood draws.

Rationale for correct answer:

4.A chest radiograph is required to confirm placement: After placement via the internal jugular or subclavian approach, a chest x-ray is required to confirm the catheter tip position (usually at the lower SVC) and to rule out immediate complications such as pneumothorax.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. This catheter usually remains in place for 2 to 3 months: Nontunneled percutaneous central lines are short‑term (usually days to a few weeks). Longer-term central access (months) is achieved with tunneled catheters or implanted ports/PICCs.

2. The catheter is introduced via the basilic or cephalic veins in the antecubital space: Basilic/cephalic antecubital veins are used for peripheral IVs or PICC insertion. Nontunneled CVCs are typically inserted into central veins (internal jugular, subclavian, or sometimes femoral).

3. Nursing responsibility includes accessing the catheter with an angled needle: Accessing with an angled (Huber) needle is how implanted ports are accessed. Nontunneled CVCs have external lumens and are accessed directly.

Take-home points

- After percutaneous central line placement, always confirm tip location and exclude pneumothorax with a chest x-ray before using the line.

- Know which device you’re dealing with: different insertion sites, expected dwell times, and access/maintenance procedures.

The nurse instructs a patient to focus on breathing more slowly as the most effective intervention for which acid–base imbalance?

Explanation

The lungs regulate the respiratory component of acid–base balance by changing CO₂ elimination. Hyperventilation lowers PaCO₂ and causes a respiratory alkalosis; hypoventilation raises PaCO₂ and causes respiratory acidosis.

Rationale for correct answer:

2. Respiratory alkalosis (carbonic acid deficit): Respiratory alkalosis results from excessive ventilation (blowing off CO₂). Slowing the breathing rate raises PaCO₂ toward normal and helps correct the alkalosis (for example, in anxiety-driven hyperventilation).

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Respiratory acidosis (carbonic acid excess): This condition is caused by CO₂ retention (hypoventilation). Asking the patient to breathe more slowly would further increase PaCO₂ and worsen the acidosis.

3. Metabolic acidosis (bicarbonate deficit): In metabolic acidosis the body compensates by increasing ventilation to blow off CO₂ (Kussmaul respirations when severe). Instructing slower breathing would reduce compensation and worsen acidemia.

4. Metabolic alkalosis (bicarbonate excess): Although retaining CO₂ (by breathing more slowly) can provide some respiratory compensation for metabolic alkalosis, this is not the typical or primary nursing intervention to treat metabolic alkalosis. T

Take home points

- Slow, controlled breathing is an effective immediate intervention for respiratory alkalosis caused by hyperventilation (e.g., panic/anxiety).

- For metabolic disturbances, encourage or treat the underlying cause - respiratory pattern changes are compensatory, not primary treatment.

When developing the teaching plan for a patient at risk for hyperkalemia, which foods would the nurse instruct the patient to avoid?

Explanation

Hyperkalemia (high serum potassium) can cause life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias. Dietary management means avoiding high-potassium foods and potassium-containing salt substitutes, and reviewing medications that raise potassium.

Rationale for correct answer:

3. Bananas and apricots (especially dried apricots), oranges, potatoes, tomatoes, beans, and certain dairy and dried fruits are among the highest dietary sources of potassium and are commonly recommended to limit in hyperkalemia.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Carrots and squash: These contain potassium but are generally moderate sources compared with fruits like bananas and many dried fruits. They are not the classic foods singled out as the highest-risk items.

2. Canned soups and potato chips: These are typically high in sodium, not the highest potassium sources. They may be unhealthy for other reasons (HTN, fluid retention) but are not the prototypical high-K foods to avoid first.

4. Whole-grain cereals and milk: Milk contains potassium (moderate amount) and some cereals contain potassium, but these are generally not as concentrated as bananas/dried fruits/potatoes.

Take home points

- Teach patients at risk for hyperkalemia to avoid obvious high-potassium foods and to not use potassium-based salt substitutes.

- Review medications and kidney function as part of hyperkalemia prevention.

- Always advise checking serum K and ECG if symptoms (weakness, palpitations) occur - and refer to a dietitian for individualized meal planning.

Which site would be most appropriate for initiating IV therapy for a patient who has sustained multiple injuries after an automobile accident and has a cast on his right arm?

Explanation

When initiating IV therapy in an emergency or multisystem trauma, choose a site that allows rapid, reliable access (large, proximal veins) in an unaffected extremity.

Rationale for correct answer:

1. Left antecubital: The antecubital fossa contains large superficial veins (e.g., median cubital, cephalic) that are easy to cannulate and allow rapid infusion - ideal in trauma when fast fluid/medication administration may be needed.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

2. Dorsal aspect of either foot: Foot veins are generally avoided in adults unless no upper-extremity sites are available (higher risk of thrombosis and slower flow). In trauma, you prefer a proximal upper-extremity site first.

3. Right hand: The right arm has a cast; avoid inserting an IV into or distal to a cast because of impaired circulation, risk of infection, and difficulty assessing the site.

4. Left forearm: The left forearm could be used, but the antecubital site provides larger, more proximal veins appropriate for rapid resuscitation- making the left antecubital more appropriate in a multisystem trauma situation.

Take home points

- For emergency IV access in trauma, pick a large, proximal vein in an uninjured limb (antecubital fossa is excellent for rapid infusion).

- Avoid IV insertion through or distal to casts, injured limbs, or areas of poor circulation; reserve foot veins for when no suitable arm veins exist.

When implementing the plan of care for a patient receiving IV therapy, which intervention would be most appropriate?

Explanation

Nursing care for IV therapy focuses on maintaining patency and safety (correct rate, preventing infection and infiltration, accurate delivery of ordered fluids/medications).

Rationale for correct answer:

4. Monitoring the flow rate at least every hour: Regular monitoring ensures the ordered infusion rate is being delivered, helps detect occlusions, infiltration, or pump failures early, and allows timely corrective action.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Changing the IV catheter and entry site daily: Routine daily removal/reinsertion is unnecessary and may increase patient discomfort and infection risk.

2. Changing the tubing every 8 hours: Tubing change intervals are set by facility/infection-control guidelines and are usually less frequent than every 8 hours for standard continuous infusions.

3. Increasing the rate to catch up if the correct amount has not been infused at the end of the shift: You should not speed an infusion without a new order- that risks fluid overload or incorrect medication dosing. Instead, notify the provider and document reasons for the delay.

Take home points

- Routinely assess the IV site and infusion (flow rate, pump alarms, tubing, site condition) - hourly checks are a safe, practical standard in many settings.

- Never alter an infusion rate to "catch up" without provider authorization; follow facility protocols for catheter/tubing changes and for troubleshooting delayed/occluded infusions.

While administering a blood transfusion, when would the nurse assess the patient for a blood transfusion reaction?

Explanation

Transfusion reactions are most likely to occur early in the transfusion (especially within the first 15 minutes). Nursing practice is to obtain baseline vitals, begin the transfusion slowly for the first few minutes, and reassess the patient shortly after starting so that acute reactions are identified and treated immediately.

Rationale for correct answer:

1. 15 minutes after the infusion is started: Most acute hemolytic and allergic transfusion reactions occur within the first 15 minutes. Standard practice is baseline vitals then start transfusion slowly then reassess the patient (vitals, symptoms) at 15 minutes.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

2. After the blood is all infused: Waiting until the end risks missing a severe early reaction; if a reaction occurs during the transfusion it can be life-threatening and requires immediate action.

3. Every hour: Hourly checks may be done after the initial period in some settings, but they are not sufficient to catch the most dangerous early reactions.

4. Every 15 minutes: Although frequent monitoring is good, the exam-focused, high-yield timing is the initial 15-minute check (and then regularly per protocol).

Take home points

Always obtain baseline vitals before a transfusion and reassess the patient about 15 minutes after starting - this is when acute reactions most commonly appear.

If a transfusion reaction is suspected:

- stop the transfusion immediately

- keep the IV patent with normal saline (new tubing)

- notify the provider and blood bank

- return the blood product per policy

- obtain required specimens (blood/urine) and documentation.

An IV fluid is infusing more slowly than ordered. The infusion pump is set correctly. Which factors could cause this slowing? Select all that apply

Explanation

When an infusion pump is set correctly but the actual infusion is slower than ordered, the problem is usually mechanical (tubing, clamps, kinks, position) or related to the catheter/vein (infiltration, occlusion). A systematic site-to-device check prevents delays and complications.

Rationale for correct answer:

1.Infiltration at VAD site; If the catheter tip or cannula has dislodged from the vein and fluid is going into the tissue, effective intravascular flow is reduced and the pump may deliver more slowly (or meet backpressure).

2. Patient lying on tubing: External compression of the tubing (patient lying on it) creates partial or complete occlusion and will slow or stop flow.

4. Tubing kinked in bedrails: A kink in the tubing increases resistance or occludes the line and will slow or stop flow.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

3. Roller clamp wide open: If the roller clamp is wide open, it would increase flow (unless something else is blocking the line). A wide-open clamp is not a cause of slowing.

5. Circulatory overload is a patient physiologic condition (too much fluid in the circulation) and would not mechanically cause the pump to run slow.

Take home points

If a pump is set correctly but infusion is slow, do a quick systematic check:

- inspect the site (for infiltration)

- follow the tubing (kinks, clamps, compression)

- check connections and pump alarms before touching infusion rates.

The nurse assesses pain and redness at a VAD site. Which action is taken first?

Explanation

Local signs at a vascular access device (VAD) site - pain, redness, swelling, warmth - suggest phlebitis, infiltration, or local infection. The nurse’s first action must protect the patient from further harm by stopping the source of the problem and preventing additional infusion into a compromised tissue/vein.

Rationale for correct answer:

4. Discontinue the IV infusion: If the site shows signs of a complication, stop the infusion immediately to prevent further tissue injury or introduction of infected/irritating fluid.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Apply a warm, moist compress: This is an appropriate treatment for phlebitis (after stopping the infusion) because it helps decrease inflammation and discomfort, but it is not the first action. You must first stop the infusion.

2. Aspirate the infusing fluid from the VAD: Aspirating the line is not the immediate priority and is not a standard first step for suspected phlebitis or local infection. Removing the IV and stopping the infusion comes first.

3. Report the situation to the health care provider: Reporting is important, but only after you’ve secured the patient (stopped the infusion and removed the catheter if indicated). Immediate safety actions come before notification.

Take-home points

- When a VAD site looks inflamed or painful, stop the infusion first - patient safety and preventing further harm are the priority.

- After stopping the infusion, follow protocol: remove the catheter if indicated, apply appropriate local measures

When delegating I&O measurement to assistive personnel, the nurse instructs them to record what information for ice chips?

Explanation

Accurate intake and output (I&O) measurement depends on standardized rules for counting foods and liquids that change volume (e.g., ice). Because ice is solid water and melts, most institutions require converting ice-chip volume to the equivalent liquid volume for accurate fluid balance.

Rationale for correct answer:

2.One-half of the volume: The usual convention is to record ice chips as 50% of their measured volume because they occupy more space as solid ice than as liquid water once melted (and because some may be lost as condensation or melting).

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1.Two-thirds of the volume: This is not the standard conversion used in clinical practice.

3. One-quarter of the volume: This underestimates intake and is not the standard conversion.

4. Two times the volume: This would grossly overestimate fluid intake.

Take-home points

- Use facility policy, but the common rule is: record ice chips as one-half of the measured volume when doing I&O.

- Be consistent: measure and document I&O the same way each shift.

A patient is admitted to the hospital with severe dyspnea and wheezing. ABG levels on admission are pH 7.26; PaO2 68 mm Hg; PaCO2 55 mm Hg; and HCO3− 24. How does the nurse interpret these laboratory values?

Explanation

Read ABGs in the order: pH → PaCO₂ → HCO₃⁻. If pH is acidotic (<7.35) determine whether the respiratory (PaCO₂) or metabolic (HCO₃⁻) component explains the change. Also note whether compensation is present (the opposing system moves toward correction).

Rationale for correct answer:

3. Respiratory acidosis: pH is low and PaCO₂ is elevated (CO₂ retention- carbonic acid excess). HCO₃⁻ is normal, suggesting an acute (or early) respiratory acidosis without renal compensation.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1.Metabolic acidosis: Metabolic acidosis would show decreased HCO₃⁻ (usually <22). Here HCO₃⁻ is normal (24).

2. Metabolic alkalosis: That would be alkalemia (pH >7.45) with increased HCO₃⁻.

4. Respiratory alkalosis: Respiratory alkalosis would have low PaCO₂ and high pH.

Take home points

- pH ↓ with PaCO₂ ↑ = respiratory acidosis (impaired ventilation/CO₂ retention).

- Normal HCO₃⁻ with an abnormal PaCO₂ suggests acute respiratory disturbance; kidneys haven’t yet compensated.

What assessments does a nurse make before hanging an IV fluid that contains potassium? Select all that apply

Explanation

IV potassium can rapidly alter serum K⁺ and cardiac conduction; it is contraindicated if renal excretion is inadequate or if serum K⁺ is already high. Nursing pre-checks focus on confirming need and safety (serum level, urine output, IV patency, ECG when indicated).

Rationale for correct answer:

1.Urine output: Adequate urine output (commonly ≥30 mL/hr in adults, or ~0.5 mL/kg/hr) is essential because kidneys excrete potassium; impaired output increases risk of hyperkalemia.

4. Serum potassium laboratory value in EHR: Always check the most recent serum K⁺ before administering IV K⁺ to avoid giving potassium to someone already hyperkalemic.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

2. ABGs assess gas exchange/acid–base status, not directly required before giving routine IV potassium. ABGs are not a standard pre-check for potassium administration.

3. Fullness of neck veins: Jugular venous distention relates to fluid volume/venous pressure, not directly to potassium handling; it’s not a standard pre-assessment for IV potassium.

5. Level of consciousness: Altered LOC can be important clinically, but it’s not a standard prerequisite assessment specifically for safely hanging K⁺. (Cardiac rhythm/ECG is the important additional check if potassium is elevated or if the patient is symptomatic.)

Take-home points

- Always verify a recent serum K⁺ and ensure the patient has adequate urine output before starting IV potassium.

- IV potassium must never be given IV push; infuse per protocol/rate limits, monitor ECG for dysrhythmias, and recheck labs as ordered.

The health care provider’s order is 500 mL 0.9% NaCl intravenously over 4 hours. Which rate does the nurse program into the infusion pump?

Explanation

Calculate infusion rate as: total volume ÷ total time= mL per hour. Use the infusion pump to program that rate and recheck calculations.

Order: 500 mL 0.9% NaCl IV over 4 hours.

500 mL ÷ 4 hr = 125 mL/hr.

Correct answer: 125 mL/hr

Take home points

- Use volume ÷ time to calculate mL/hr and program the pump accordingly.

- Always double-check calculations, verify the order and the pump setting, ensure IV patency

Exams on Fluids and Electrolytes & Acid-Base Balance

Custom Exams

Login to Create a Quiz

Click here to loginLessons

Naxlex

Just Now

Naxlex

Just Now

- Objectives

- Introduction

- Fluid Compartments

- Fluid Balance

- Electrolytes

- Movement Of Body Fluids And Electrolytes

- Practice Exercise 1

- Fluid Imbalances

- Electrolyte Imbalances

- Practice Exercise 2

- Acid Base Imbalances

- Respiratory Acid-base Imbalances

- Metabolic Acid-base Imbalances

- The Nursing Process For Fluid, Electrolyte, And Acid–base Balance

- Practice Exercise 3

- Summary

- Comprehensive Questions

Notes Highlighting is available once you sign in. Login Here.

Objectives

- Determine what processes regulate fluid distribution, extracellular fluid volume (ECV), and body fluid osmolality.

- Explain processes that regulate electrolyte balance.

- Explain processes that regulate acid-base balance.

- Recall common fluid, electrolyte, and acid-base imbalances.

- Identify risk factors for fluid, electrolyte, and acid-base imbalances

- Explain rationale and procedures for initiating and discontinuing an intravenous (IV) line.

Introduction

In good health, a delicate balance of fluids, electrolytes, acids, and bases maintains the body.

This balance, or homeostasis, depends on multiple physiological processes that regulate fluid intake and output, as well as the movement of water and the substances dissolved in it between body compartments.

Fluid Compartments

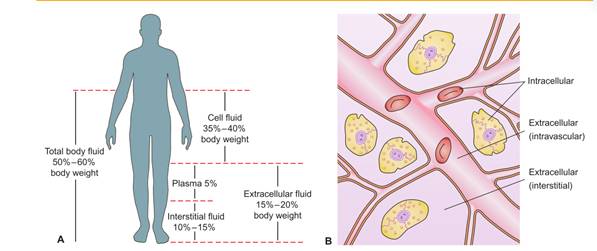

3.1 FLUID COMPARTMENTS

The body’s fluid is contained within three compartments: cells, blood vessels, and the tissue space (space between the cells and blood vessels).

There are two types of body fluid:

- intracellular fluid (ICF)- found within the cells of the body. It constitutes approximately two thirds of the total body fluid in adults.

- extracellular fluid (ECF)- found outside the cells and accounts for about one third of total body fluid.

ECF is further subdivided into compartments. The two main compartments of ECF are:

- Intravascular-or plasma, accounts for approximately 20% of ECF and is found within the vascular system

- Interstitial- accounting for approximately 75% of ECF, surrounds the cells.

The other compartments of ECF include the lymph and transcellular fluids (cerebrospinal, pericardial, pancreatic, pleural, intraocular, biliary, peritoneal, and synovial fluids).

Water in the body functions primarily to:

- Provide a medium for transporting nutrients to cells and wastes from cells

- Provide a medium for transporting substances such as hormones, enzymes, blood platelets, and red and white blood cells throughout the body

- Facilitate cellular metabolism and proper cellular chemical functioning

- Act as a solvent for electrolytes and nonelectrolytes

- Help maintain normal body temperature

- Facilitate digestion and promote elimination

- Act as a tissue lubricant

Variations in Fluid content:

Variations in the fluid content from the normal 50% to 60% of the body’s weight can occur, depending on such factors as the person’s age, body fat, and gender.

Fat cells contain little water, whereas lean tissue is rich in water. Thus, the more obese a person is, the smaller the person’s percentage of total body water is when compared with body weight.

- Because women tend to have proportionally more body fat than men do, they also have less body fluid than men.

- Older adults lose muscle mass as a part of aging. The combined increase of fat and loss of muscle results in reduced total body water; after the age of 60, total body water is about 45% of a person’s body weight.

- Infants have considerably more total body fluid and ECF than adults. Because ECF is more easily lost from the body than ICF, infants are more prone to fluid volume deficits.

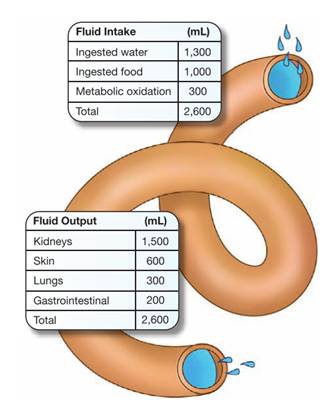

Fluid Balance

The desirable amount of fluid intake and loss in adults ranges from 1,500 to 3,500 mL each 24 hours.

A person’s intake should normally be approximately balanced by output or fluid loss.

In healthy adults, the output of urine normally approximates the ingestion of liquids, and the water from food and oxidation is balanced by the water loss through the feces, the skin, and the respiratory process.

Fluid sources:

The human body obtains water from several sources, including ingested liquids, food, and as a by-product of metabolism.

Fluid losses:

Fluid is lost from the body through sensible and insensible losses.

- Sensible losses can be measured and include fluid lost during urination, defecation, and wounds.

- Insensible losses can’t be measured or seen and include fluid lost from evaporation through the skin and as water vapor from the lungs during respiration.

Homeostatic mechanisms:

Almost every organ and system in the body helps in some way to maintain fluid homeostasis.

- Kidneys:

- Regulate extracellular fluid (ECF) volume and osmolality by selective retention and excretion of body fluids

- Regulate electrolyte levels in the ECF by selective retention of needed substances and excretion of unneeded substances

- Regulate pH of ECF by excretion or retention of hydrogen ions

- Excrete metabolic wastes (primarily acids) and toxic substances

- Heart and blood vessels:

- Circulate blood through the kidneys under sufficient pressure for urine to form (pumping action of the heart)

- React to hypovolemia by stimulating fluid retention (stretch receptors in the atria and blood vessels).

- Lungs:

- Eliminate about 13,000 mEq of hydrogen ions (H+) daily.

- Act promptly to correct metabolic acid–base disturbances; regulate H+ concentration (pH) by controlling the level of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the extracellular fluid as follows:

- Metabolic alkalosis causes compensatory hypoventilation, resulting in CO2 retention.

- Metabolic acidosis causes compensatory hyperventilation, resulting in CO2 excretion.

- Remove approximately 300 mL of water daily through exhalation (insensible water loss) in the normal adult.

- Adrenal glands:

- Regulate blood volume and sodium and potassium balance by secreting aldosterone:

- The primary regulator of aldosterone appears to be angiotensin II, which is produced by the renin–angiotensin system. A decrease in blood volume triggers this system and increases aldosterone secretion, which causes sodium retention (and thus water retention) and potassium loss.

- Decreased secretion of aldosterone causes sodium and water loss and potassium retention.

- Cortisol, another adrenocortical hormone, has only a fraction of the potency of aldosterone.

- However, secretion of cortisol in large quantities can produce sodium and water retention and potassium deficit.

- Pituitary gland:

- Stores and releases the antidiuretic hormone (ADH):

- Maintains osmotic pressure of the cells by controlling renal water retention or excretion

- When osmotic pressure of the ECF is greater than that of the cells (as in hypernatremia— excess sodium—or hyperglycemia), ADH secretion is increased, causing renal retention of water.

- When osmotic pressure of the ECF is less than that of the cells (as in hyponatremia), ADH secretion is decreased, causing renal excretion of water.

- Controls blood volume (less influential than aldosterone)

- When blood volume is decreased, an increased secretion of ADH results in water conservation.

- When blood volume is increased, a decreased secretion of ADH results in water loss.

- Nervous system

- Inhibits and stimulates mechanisms influencing fluid balance; acts chiefly to regulate sodium and water intake and excretion.

- Regulates oral intake by sensing intracellular dehydration, which triggers thirst (thirst center located in hypothalamus).

- Parathyroid gland

- Regulate calcium (Ca2+) and phosphate (HPO4 2-) balance by means of parathyroid hormone (PTH);

- PTH influences bone reabsorption, calcium absorption from the intestines, and calcium reabsorption from the renal tubules.

- Increased secretion of PTH causes: a. Elevated serum calcium concentration b. Lowered serum phosphate concentration

- Conversely, decreased secretion of PTH causes: a. Lowered serum calcium concentration b. Elevated serum phosphate concentration.

Electrolytes

Electrolytes are substances that are capable of breaking into particles called ions.

An ion is an atom or molecule carrying an electrical charge.

- Some ions develop a positive charge and are called cations. The major cations in body fluid are sodium, potassium, calcium, hydrogen, and magnesium ions.

- Other ions develop a negative charge and are called anions. The major anions in body fluid are chloride, bicarbonate, and phosphate.

Fluids in various compartments of the body differ in their constituents.

- Major electrolytes in the ECF include sodium, chloride, calcium, and bicarbonate.

- Major electrolytes in the ICF include potassium, phosphorus, and magnesium.

Major electrolytes:

|

Electrolyte |

Functions |

Sources & Losses |

Regulation |

|

Sodium (Na+): 135–145 mEq/L |

Transmission of nerve impulses

|

Derived easily from dietary sources, such as salt added to processed foods, sodium preservatives added to processed foods

Lost from gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, and skin |

Transported out of the cell by the sodium potassium pump Sodium concentrations affected by salt, as well as water, intake Regulated by renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system Elimination and reabsorption regulated by the kidneys |

|

Potassium (K+): 3.5–5.0 mEq/L |

|

Adequate quantities usually in a well-balanced diet Leading food sources: fruits and vegetables, dried peas and beans, whole grains, milk, meats Lost via kidneys, stool, sweat Gastrointestinal (GI) secretions contain potassium in large quantities, so can be lost through vomitus |

Regulated by aldosterone Eliminated by the kidneys (no effective method of conserving potassium) Additional regulation via transcellular shift between the ICF and ECF compartments |

|

Calcium (Ca2+): Total serum calcium level: 8.6–10.2 mg/dL Ionized serum calcium level: 4.5–5.1 mg/dL

|

|

Absorbed from foods in the presence of normal gastric acidity and vitamin D

Sources include milk, milk products, cheese, and dried beans; fortified orange juice; green leafy vegetables, small fish with bones, and dried peas and beans

Lost via feces and urine

|

Primarily excreted by gastrointestinal tract; lesser extent by kidneys

Regulated by parathyroid hormone and calcitonin

High serum phosphate results in decreased serum calcium level; low serum phosphate leads to increased serum calcium |

|

Magnesium (Mg2+): 1.3–2.3 mEq/L |

|

Enters the body via gastrointestinal tract Magnesium found in green leafy vegetables, nuts, seafood, whole grains, dried peas and beans; cocoa

Lost via urine with use of loop diuretics |

Eliminated by kidneys Regulated by parathyroid hormone |

|

Chloride (Cl-): 97–107 mEq/L |

|

Enters body via gastrointestinal tract Almost all chloride in diet comes from salt Found in foods high in sodium, processed foods |

Normally paired with sodium; excreted and conserved with sodium by the kidneys Regulated by aldosterone alongside sodium Low potassium level leads to low chloride level |

|

Bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻ ) |

|

Losses possible via diarrhea, diuretics, and early renal insufficiency; excess possible via over ingestion of acid neutralizers, such as sodium bicarbonate |

Bicarbonate levels regulated primarily by the kidneys Bicarbonate readily available as a result of carbon dioxide formation during metabolism |

|

Phosphate (PO4 -): |

|

Enters body via gastrointestinal tract Sources include all animal products (meat, poultry, eggs, milk, bread, ready-to-eat cereal) Absorption is diminished by concurrent ingestion of calcium, magnesium, and aluminum |

Eliminated by kidneys Regulation by parathyroid hormone and by activated vitamin D Phosphate and calcium are inversely proportional; an increase in one results in a decrease in the other |

Movement Of Body Fluids And Electrolytes

Key terms used in explaining the movement of molecules in body fluids are:

• Solute: Substance dissolved in a solution

• Solvent: Liquid that contains a substance in solution

• Permeability: Capability of a substance, molecule, or ion to diffuse through a membrane (covering of tissue over a surface, organ, or separating spaces)

• Semipermeable: Selectively permeable (All membranes in the body allow some solutes to pass through the membrane without restriction but will prevent the passage of other solutes.)

Permeability allows the cell to acquire the nutrients it needs from ECF to carry on metabolism and to eliminate metabolic waste products.

The concentration of solutes in body fluids is usually expressed as the osmolality.

Solutions may be termed isotonic, hypertonic, or hypotonic.

- An isotonic solution has the same osmolality as ECF Eg. Normal saline, 0.9% sodium chloride.

- Hypertonic solutions, such as 3% sodium chloride, have a higher osmolality than ECF.

- Hypotonic solutions, such as 0.45% sodium chloride, have a lower osmolality than ECF.

Osmotic pressure is the power of a solution to pull water across a semipermeable membrane

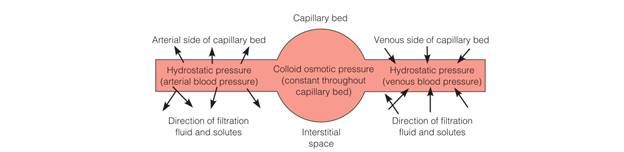

Plasma proteins also exert osmotic pressure called colloid osmotic pressure or oncotic pressure, holding water in plasma, and when necessary pulling water from the interstitial space into the vascular compartment.

Hydrostatic pressure is the pressure exerted by a fluid within a closed system on the walls of the container in which it is contained.

- Diffusion occurs when two solutes of different concentrations are separated by a semipermeable membrane.

- Osmosis: specific kind of diffusion in which water moves across cell membranes, from the less concentrated solution.

- Filtration is a process whereby fluid and solutes move together across a membrane from an area of higher pressure to an area of lower pressure.

- Active transport is the movement of solutes across cell membranes from a less concentrated solution to a more concentrated one.

Fluid Imbalances

Fluid imbalances are of two basic types: isotonic and osmolar.

Isotonic imbalances occur when water and electrolytes are lost or gained in equal proportions, so that the osmolality of body fluids remains constant.

Osmolar imbalances involve the loss or gain of only water, so that the osmolality of the serum is altered.

Thus, four categories of fluid imbalances may occur:

-

- an isotonic loss of water and electrolytes- fluid volume deficit

- an isotonic gain of water and electrolytes- fluid volume excess

- a hyperosmolar loss of only water- hyperosmolar imbalance/ dehydration

- a hypo-osmolar gain of only water- overhydration (hypo-osmolar imbalance)

1. FLUID VOLUME DEFICIT:

Isotonic fluid volume deficit (FVD) occurs when the body loses both water and electrolytes from the ECF in similar proportions. Thus, the decreased volume of fluid remains isotonic.

In FVD, fluid is initially lost from the intravascular compartment, so it often is called hypovolemia. FVD generally occurs as a result of

- abnormal losses through the skin, gastrointestinal tract, or kidney

- decreased intake of fluid due to anorexia, nausea, inability to access fluids, impaired swallowing, confusion, depression

- bleeding

- movement of fluid into a third space

Clinical manifestations:

- Complaints of weakness and thirst

- Weight loss: • 2% loss = mild FVD • 5% loss = moderate • 8% loss = severe

- Decreased tissue turgor

- Dry mucous membranes, sunken eyeballs, decreased tearing

- Subnormal temperature

- Weak pulse; tachycardia Decreased blood pressure

- Postural (orthostatic) hypotension (significant drop in BP when moving from lying to sitting or standing position)

- Decreased capillary refill

- Decreased central venous pressure

- Decreased urine volume (<30 mL/hr)

- Increased specific gravity of urine (>1.030)

- Increased hematocrit

- Increased blood urea nitrogen (BUN)

Nursing interventions:

- Assess for clinical manifestations of FVD.

- Monitor weight and vital signs, including temperature.

- Assess tissue turgor.

- Monitor fluid intake and output.

- Monitor laboratory findings.

- Administer oral and IV fluids as indicated.

- Provide frequent mouth care.

- Implement measures to prevent skin breakdown.

- Provide for safety (e.g., provide assistance for a client rising from bed or chair).

Third space syndrome:

In third space syndrome, fluid shifts from the vascular space into an area where it is not readily accessible as extracellular fluid.

Third spacing has two distinct phases: loss and reabsorption.

The client with third space syndrome during the loss phase has an isotonic fluid deficit. During the reabsorption phase, tissues begin to heal and fluid moves back into the intravascular space

Because fluid shifts from the vascular compartment (loss phase) and then back into the vascular compartment after time (reabsorption phase), assessment for manifestations of fluid volume deficit and excess is vital.

2. FLUID VOLUME EXCESS

Fluid volume excess (FVE) occurs when the body retains both water and sodium in similar proportions to normal ECF.

This is commonly referred to as hypervolemia (increased blood volume).

Specific causes of FVE include:

- excessive intake of sodium chloride

- administering sodium-containing infusions too rapidly, particularly to clients with impaired regulatory mechanisms

- disease processes that alter regulatory mechanisms, such as heart failure, renal failure, cirrhosis of the liver, and Cushing’s syndrome.

Clinical manifestations:

- Weight gain: • 2% gain = mild FVE • 5% gain = moderate • 8% gain = severe

- Fluid intake greater than output

- Full, bounding pulse; tachycardia Increased blood pressure and central venous pressure

- Distended neck veins

- Moist crackles (rales) in lungs; dyspnea, shortness of breath

- Edema

- Mental confusion

Nursing interventions:

- Assess for clinical manifestations of FVE.

- Monitor weight and vital signs.

- Assess for edema.

- Assess breath sounds.

- Monitor fluid intake and output.

- Monitor laboratory findings.

- Place in Fowler’s position.

- Administer diuretics as ordered.

- Restrict fluid intake as indicated.

- Restrict dietary sodium as ordered.

- Implement measures to prevent skin breakdown.

3. DEHYDRATION

Dehydration, or a hyperosmolar fluid imbalance, occurs when water is lost from the body, leaving the client with excess sodium.

Water is drawn into the vascular compartment from the interstitial space and cells, resulting in cellular dehydration.

4. OVERHYDRATION

Overhydration, or a hypo-osmolar fluid imbalance, occurs when water is gained in excess of electrolytes, resulting in low serum osmolality and low serum sodium levels.

Electrolyte Imbalances

a. Hyponatremia:

Is a sodium deficit, or serum sodium level of less than 135 mEq/L.

Risk factors:

Loss of Sodium

- Gastrointestinal fluid loss

- Sweating

- Use of diuretics

Gain of Water

- Hypotonic tube feedings

- Excessive drinking of water

- Excess IV D5W (dextrose in water) administration

Syndrome of Inappropriate ADH (SIADH)

- Head injury

- AIDS

- Malignant tumors

Clinical manifestations

- Lethargy, confusion, apprehension

- Muscle twitching

- Abdominal cramps

- Anorexia, nausea, vomiting

- Headache

- Seizures, coma

- Laboratory findings: Serum sodium < 135 mEq/L Serum osmolality < 280 mOsm/kg

Nursing interventions

- Assess clinical manifestations.

- Monitor fluid intake and output.

- Monitor laboratory data (e.g., serum sodium).

- Assess client closely if administering hypertonic saline solutions.

- Encourage food and fluid high in sodium if permitted (e.g., table salt, bacon, ham, processed cheese).

- Limit water intake as indicated.

b. Hypernatremia

Risk factors

Loss of Water

- Insensible water loss (hyperventilation or fever)

- Diarrhea

- Water deprivation

Gain of Sodium

- Parenteral administration of saline solutions

- Hypertonic tube feedings without adequate water

- Excessive use of table salt (1 tsp contains 2,300 mg of sodium)

- Conditions such as: • Diabetes insipidus • Heat stroke

Clinical manifestations

- Thirst

- Dry, sticky mucous membranes

- Tongue red, dry, swollen Weakness

- Severe hypernatremia:

- Fatigue, restlessness • Decreasing level of consciousness • Disorientation • Convulsions

- Laboratory findings: Serum sodium > 145 mEq/L Serum osmolality > 300 mOsm/kg

Nursing interventions:

- Monitor fluid intake and output.

- Monitor behavior changes (e.g., restlessness, disorientation).

- Monitor laboratory findings (e.g., serum sodium).

- Encourage fluids as ordered.

- Monitor diet as ordered (e.g., restrict intake of salt and foods high in sodium).

c. Hypokalemia

Risk factors:

- Vomiting and gastric suction

- Diarrhea

- Heavy perspiration

- Use of potassium-wasting drugs (e.g., diuretics)

- Poor intake of potassium (as with debilitated clients, alcoholics, anorexia nervosa)

- Hyperaldosteronism

Clinical manifestations:

- Muscle weakness, leg cramps

- Fatigue, lethargy

- Anorexia, nausea, vomiting

- Decreased bowel sounds, decreased bowel motility

- Cardiac dysrhythmias

- Depressed deep-tendon reflexes

- Weak, irregular pulses

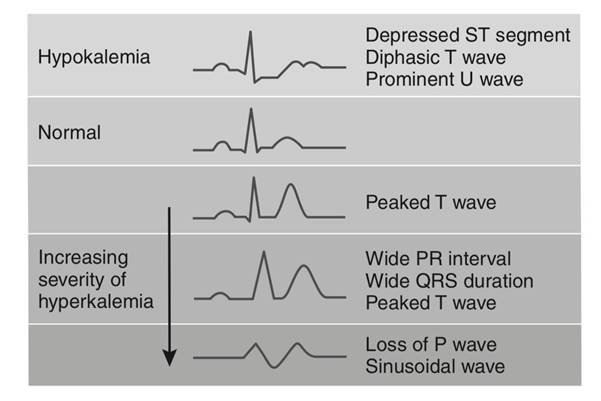

- Laboratory findings: Serum potassium < 3.5 mEq/L Arterial blood gases (ABGs) may show alkalosis T-wave flattening and ST-segment depression on ECG.

Nursing interventions:

- Monitor heart rate and rhythm.

- Monitor clients receiving digitalis (e.g., digoxin) closely, because hypokalemia increases risk of digitalis toxicity.

- Administer oral potassium as ordered with food or fluid to prevent gastric irritation.

- Administer IV potassium solutions at a rate no faster than 10–20 mEq/h; never administer undiluted potassium intravenously.

- For clients receiving IV potassium, monitor for pain and inflammation at the injection site.

- Teach client about potassium-rich foods.

- Teach clients how to prevent excessive loss of potassium (e.g., through abuse of diuretics and laxatives).

d. Hyperkalemia

Risk factors:

Decreased Potassium Excretion

- Renal failure

- Hypoaldosteronism

- Potassium-conserving diuretics

High Potassium Intake

- Excessive use of K+ containing salt substitutes

- Excessive or rapid IV infusion of potassium

- Potassium shift out of the tissue cells into the plasma (e.g., infections, burns, acidosis)

Clinical manifestations:

- Gastrointestinal hyperactivity, diarrhea

- Irritability, apathy, confusion

- Cardiac dysrhythmias or arrest

- Muscle weakness, areflexia (absence of reflexes)

- Decreased heart rate Irregular pulse

- Paresthesias and numbness in extremities

- Laboratory findings: Serum potassium > 5.0 mEq/L Peaked T wave, widened QRS on ECG

Nursing interventions:

- Closely monitor cardiac status and ECG.

- Administer diuretics and other medications such as glucose and insulin as ordered.

- Hold potassium supplements and K+ conserving diuretics.

- Monitor serum K+ levels carefully; a rapid drop may occur as potassium shifts into the cells.

- Teach clients to avoid foods high in potassium and salt substitutes.

e. Hypocalcemia:

Risk factors:

Surgical Removal of the Parathyroid Glands

Conditions such as:

- Hypoparathyroidism

- Acute pancreatitis

- Hyperphosphatemia

- Thyroid carcinoma

Inadequate Vitamin D Intake

- Malabsorption

- Hypomagnesemia

- Alkalosis

- Sepsis

- Alcohol abuse

Clinical manifestations:

- Numbness, tingling of the extremities and around the mouth

- Muscle tremors, cramps; if severe can progress to tetany and convulsions

- Cardiac dysrhythmias; decreased cardiac output

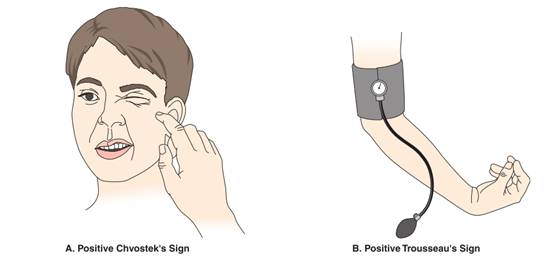

- Positive Trousseau’s and Chvostek’s signs

- Confusion, anxiety, possible psychoses

- Hyperactive deep-tendon reflexes

- Laboratory findings: Serum calcium < 8.5 mg/dL (total) or 4.5 mEq/L (ionized) Lengthened QT intervals Prolonged ST segments

Nursing interventions:

Closely monitor respiratory and cardiovascular status. Take precautions to protect a confused client. Administer oral or parenteral calcium supplements as ordered.

When administering intravenously, closely monitor cardiac status and ECG during infusion. Teach clients at high risk for osteoporosis about:

- Dietary sources rich in calcium.

- Recommendation for 1,000–1,500 mg of calcium per day.

- Calcium supplements.

- Regular exercise.

- Estrogen replacement therapy for postmenopausal women.

f. Hypercalcemia:

Risk factors:

Prolonged immobilization

Conditions such as:

- Hyperparathyroidism

- Malignancy of the bone

- Paget’s disease

Clinical manifestations:

- Lethargy, weakness

- Depressed deep-tendon reflexes

- Bone pain

- Anorexia, nausea, vomiting

- Constipation Polyuria, hypercalciuria

- Flank pain secondary to urinary calculi

- Dysrhythmias, possible heart block

- Laboratory findings: Serum calcium > 10.5 mg/dL (total) or 5.5 mEq/L (ionized)

- ECG: Shortened QT intervals, Shortened ST segments

Nursing interventions:

- Increase client movement and exercise.

- Encourage oral fluids as permitted to maintain a dilute urine.

- Teach clients to limit intake of food and fluid high in calcium.

- Encourage ingestion of fiber to prevent constipation.

- Protect a confused client; monitor for pathologic fractures in clients with long-term hypercalcemia.

- Encourage intake of acid–ash fluids (e.g., prune or cranberry juice) to counteract deposits of calcium salts in the urine.

g. Hypomagnesemia:

Risk factors:

- Excessive loss from the gastrointestinal tract (e.g., from nasogastric suction, diarrhea, fistula drainage)

- Long-term use of certain drugs (e.g., diuretics, aminoglycoside antibiotics)

- Conditions such as:

- Chronic alcoholism

- Pancreatitis

- Burns

Clinical manifestations:

- Neuromuscular irritability with tremors

- Increased reflexes, tremors, convulsions

- Positive Chvostek’s and Trousseau’s signs

- Tachycardia, elevated blood pressure, dysrhythmias

- Disorientation and confusion

- Vertigo

- Anorexia, dysphagia

- Respiratory difficulties

Laboratory findings: Serum magnesium < 1.5 mEq/L

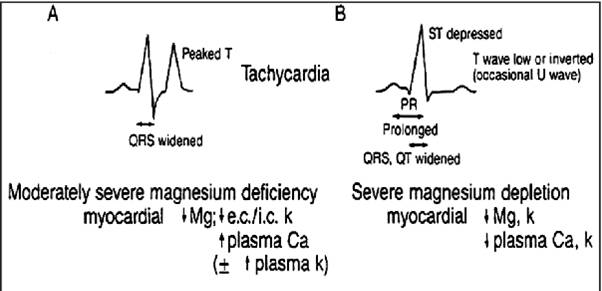

ECG: Prolonged PR intervals, widened QRS complexes, prolonged QT intervals, broad flattened T waves, prominent U waves

Nursing interventions

Assess clients receiving digitalis for digitalis toxicity.

Hypomagnesemia increases the risk of toxicity.

Take protective measures when there is a possibility of seizures:

- Assess the client’s ability to swallow water prior to initiating oral feeding.

- Initiate safety measures to prevent injury during seizure activity.

- Carefully administer magnesium salts as ordered

Encourage clients to eat magnesium-rich foods if permitted (e.g., whole grains, meat, seafood, and green leafy vegetables).

Refer clients to alcohol treatment programs as indicated.

h. Hypermagnesemia:

Risk factors:

Abnormal retention of magnesium, as in:

- Renal failure

- Adrenal insufficiency

- Treatment with magnesium salts

Clinical manifestations:

- Peripheral vasodilation, flushing

- Nausea, vomiting

- Muscle weakness, paralysis

- Hypotension, bradycardia

- Depressed deep-tendon reflexes

- Lethargy, drowsiness

- Respiratory depression, coma

- Respiratory and cardiac arrest if hypermagnesemia is severe

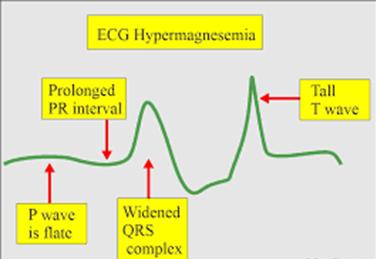

- Laboratory findings: Serum magnesium > 2.5 mEq/L Electrocardiogram showing prolonged QT interval, prolonged PR interval, widened QRS complexes, tall T waves

Nursing interventions:

- Monitor vital signs and level of consciousness when clients are at risk. If patellar reflexes are absent, notify the primary care provider.

- Advise clients who have renal disease to contact their primary care provider before taking over-the-counter drugs.

Acid Base Imbalances

Hydrogen ions: Vital to life because hydrogen ions determine the pH of the body, which must be maintained in a narrow range between 7.35 and 7.45.

Acids: Produced as end products of metabolism and contain hydrogen ions.

Bases: Are considered hydrogen ion acceptors; they accept hydrogen+ ions from acids to neutralize or decrease the strength of a base or to form a weaker acid. Normal serum levels of bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻ ) are 21 to 28 mEq/L (21 to 28 mmol/L).

Regulatory Systems for Hydrogen ion concentration in the blood

Include:

- Buffers

- Lungs

- Kidneys

- BUFFERS:

Are reactors that function only to keep the pH within the narrow limits of stability.

Buffers absorb or release hydrogen ions as needed.

|

Hemoglobin |

Plasma protein system |

Carbonic acid–bicarbonate system |

Phosphate buffer system |

|

Maintains acid-base balance by a process called chloride shift. |

Functions along with the liver to vary the amount of hydrogen ions in the chemical structure of plasma proteins |

Carbonic acid concentration is controlled by the excretion of CO2 by the lungs; the rate and depth of respiration change in response to changes in the CO2 e. The kidneys control the bicarbonate concentration and selectively retain or excrete bicarbonate in response to bodily needs |

Acts like bicarbonate and neutralizes excess hydrogen ions. |

- LUNGS

They interact with the buffer system to maintain acid-base balance.

- During acidosis, the pH decreases and the respiratory rate and depth increase in an attempt to exhale acids. The carbonic acid created by the neutralizing action of bicarbonate can be carried to the lungs, where it is reduced to CO2 and water and is exhaled; thus, hydrogen ions are inactivated and exhaled.

- During alkalosis, the pH increases and the respiratory rate and depth decrease; CO2 is retained and carbonic acid increases to neutralize and decrease the strength of excess bicarbonate.

- KIDNEYS

- During acidosis, the pH decreases and excess hydrogen ions are secreted into the tubules and combine with buffers for excretion in the urine.

- During alkalosis, the pH increases and excess bicarbonate ions move into the tubules, combine with sodium, and are excreted in the urine.