Please set your exam date

Pain

Study Questions

Practice Exericise 1

A. According to the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), what is the most accurate definition of pain?

Explanation

The IASP defines pain as a subjective, unpleasant sensory and emotional experience linked to actual or potential tissue damage, or described in such terms. This emphasizes that pain is not only a physical sensation but also an emotional experience, making patient self-report the gold standard in pain assessment.

Rationale for correct answer:

B. A subjective, unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage: This definition recognizes that pain has both sensory and emotional components and may occur even in the absence of visible injury. It also underlines that only the patient can truly describe their pain.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

A. Purely physical sensation: This oversimplifies pain by ignoring its emotional and subjective aspects.

C. Objective measure of tissue injury: Pain cannot be objectively quantified by the extent of injury; mild injuries can cause severe pain and vice versa.

D. Psychological symptom with no physiological basis: This dismisses the legitimate physical basis of many types of pain and stigmatizes the patient’s experience.

Take home points:

- Pain is a complex, multifaceted experience involving sensory and emotional factors.

- Self-report remains the most reliable method for pain assessment.

- Understanding the IASP definition helps guide holistic pain management.

The experience of pain is multifaceted and includes several dimensions. Select all the components that are considered part of the multidimensional nature of pain. Select all that apply

Explanation

Pain is a multidimensional experience that goes beyond physical sensations. It includes sensory (location, intensity, quality), affective (emotional impact), behavioral (actions taken in response), cognitive (thoughts, beliefs, and attitudes about pain), and spiritual (meaning, purpose, and personal beliefs related to suffering) components. Recognizing these aspects allows healthcare providers to deliver holistic pain management.

Rationale for correct answers:

A. Sensory: This relates to the physical perception of pain, including intensity, location, and type (sharp, dull, burning).

B. Affective: Pain can trigger emotions such as fear, anxiety, or depression, which influence how it is perceived and tolerated.

C. Behavioral: This includes observable actions in response to pain, such as grimacing, guarding, or seeking relief.

D. Cognitive: Thoughts, beliefs, and understanding about the cause and meaning of pain can shape a person’s pain experience.

E. Spiritual: Pain may affect or be influenced by personal beliefs, life meaning, or existential concerns, especially in chronic or terminal illness.

Take home points:

- Pain is not purely a physical symptom; it is shaped by emotional, mental, behavioral, and spiritual factors.

- Holistic pain assessment should explore all these dimensions to ensure comprehensive management.

- Addressing only the sensory component risks under-treating the true impact of pain.

Unrelieved acute pain has several negative physiological consequences. A significant increase in heart rate and blood pressure is primarily caused by which of the following?

Explanation

Unrelieved acute pain stimulates the body’s stress response, activating the sympathetic nervous system. This leads to the release of catecholamines such as epinephrine and norepinephrine, which cause increased heart rate, elevated blood pressure, and heightened myocardial oxygen demand. These physiological changes are part of the "fight-or-flight" response, preparing the body to react to perceived danger but potentially harmful when prolonged, especially in patients with cardiovascular disease.

Rationale for correct answer:

C. Sympathetic nervous system activation: Acute pain signals trigger the hypothalamus, which activates the sympathetic nervous system. This results in vasoconstriction, increased cardiac contractility, and elevated heart rate and blood pressure — all aimed at improving perfusion during stress, but potentially detrimental if sustained.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

A. Parasympathetic nervous system activation: This system slows the heart rate and lowers blood pressure, the opposite of what occurs with unrelieved acute pain.

B. The release of endorphins: Endorphins are natural pain-relieving peptides that reduce the perception of pain and can lower sympathetic activity, not increase it.

D. A reduction in cardiac output: Unrelieved acute pain generally increases cardiac output due to sympathetic stimulation, not decreases it — unless pain is severe enough to cause decompensation in a compromised heart.

Take home points

- Acute pain activates the sympathetic nervous system, increasing HR and BP.

- Catecholamine release is a key mechanism in this physiological stress response.

- Prolonged sympathetic activation can have harmful effects, especially in patients with cardiac conditions.

- Effective pain control can help stabilize vital signs and prevent cardiovascular complications.

Unrelieved chronic pain can have significant long-term consequences on a patient's life. Select all the potential psychosocial consequences of unrelieved chronic pain.

Explanation

Unrelieved chronic pain affects not only physical well-being but also emotional, social, and behavioral health. Persistent pain interferes with daily activities, reduces mobility, and disrupts sleep patterns. Over time, it can contribute to anxiety, depression, and feelings of hopelessness. Social withdrawal is common as patients avoid activities or relationships due to discomfort, and some individuals may resort to substance use either as a coping mechanism or due to prolonged opioid therapy increasing the risk of dependence or misuse.

Rationale for correct answers:

- Decreased mobility and physical function: Pain discourages movement, leading to muscle deconditioning, joint stiffness, and reduced independence.

- Anxiety and depression: Chronic pain alters brain chemistry and can erode emotional resilience, increasing the risk of mood disorders.

- Sleep disturbances: Pain can make it difficult to fall asleep or stay asleep, leading to fatigue, irritability, and impaired concentration.

- Social isolation and withdrawal: Patients may limit social interactions to avoid pain triggers or due to reduced energy, impacting relationships.

- Increased risk of substance use: The ongoing struggle to manage pain can lead to misuse of prescription pain medication or illicit substances.

Take home points

- Chronic pain impacts physical, emotional, and social health.

- Anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbances are common in long-term pain sufferers.

- Social withdrawal can worsen mental health and reduce support systems.

- Effective pain management requires a holistic approach addressing both physical and psychosocial needs.

A patient's statement, "I am so afraid this pain will never go away," primarily reflects which dime nsion of their pain experience?

Explanation

The statement reflects the affective dimension of pain, which encompasses the emotional responses and feelings associated with pain. Fear, anxiety, frustration, and hopelessness are common affective reactions that can amplify the perception of pain and affect a patient’s overall well-being.

Rationale for correct answer:

D. The affective dimension: This relates to the emotional aspects of the pain experience, including fear, anger, sadness, or distress. Fear about pain persistence is a classic affective response that can worsen pain perception and hinder coping strategies.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

- The sensory dimension: Focuses on the physical qualities of pain such as location, intensity, and quality (e.g., burning, throbbing), not emotions.

- The behavioral dimension: Involves observable actions taken in response to pain, such as grimacing, restlessness, or avoidance of activity.

- The cognitive dimension: Pertains to beliefs, attitudes, and expectations about pain, such as thoughts about its cause or meaning, but does not directly capture emotional fear.

Take home points

- Pain is multidimensional; sensory, affective, cognitive, and behavioral aspects all interact.

- The affective dimension captures the emotional toll of pain, such as fear, anxiety, or depression.

- Addressing emotional responses is crucial for effective pain management.

Practice Exercise 2

The process of pain transmission involves several key steps. Which of the following correctly describe events that occur during this process? Select all that apply

Explanation

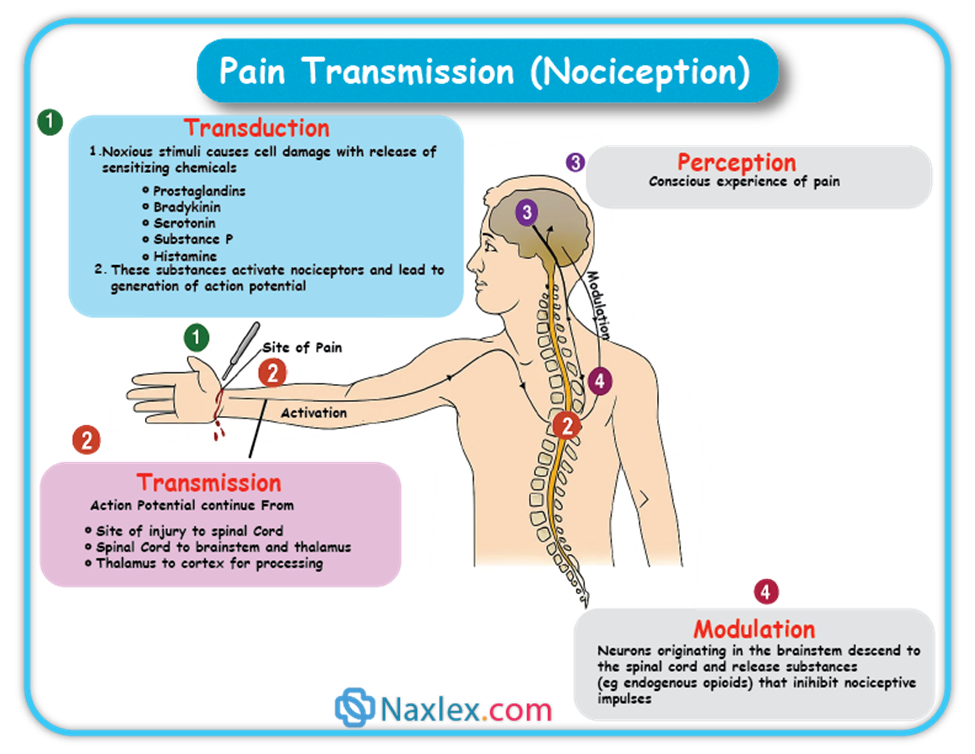

Pain transmission is a multi-step process involving transduction, transmission, perception, and modulation. Transduction converts noxious stimuli into electrical impulses, transmission carries these impulses from the site of injury to the CNS, perception is the conscious recognition of pain, and modulation involves signals from the brain that can either enhance or suppress pain transmission. Descending pathways play a key role in modulation, using inhibitory neurotransmitters to reduce pain signals.

Rationale for correct answers:

A. Transduction is the conversion of a noxious stimulus into an electrical signal: This occurs at the nociceptor level when mechanical, thermal, or chemical stimuli are transformed into action potentials.

B. Modulation involves the release of inhibitory neurotransmitters to reduce pain signals: Neurotransmitters like serotonin, norepinephrine, and endogenous opioids inhibit ascending pain transmission.

C. Transmission is the movement of a pain signal from the periphery to the central nervous system: Involves the dorsal horn of the spinal cord and ascending pathways to the brain.

E. Descending pathways originating in the brain can block or enhance pain transmission: These pathways can release inhibitory or excitatory neurotransmitters to alter pain perception.

Rationale for incorrect answer:

D. Perception is the point at which the electrical signal is converted back into a chemical signal: Perception is the conscious awareness and interpretation of pain, occurring in the brain. It does not involve reversing the signal into a chemical form.

Take home points

- Pain processing involves transduction, transmission, perception, and modulation.

- Inhibitory neurotransmitters and descending pathways are key in controlling pain.

- Perception is a brain function, not a chemical reconversion process.

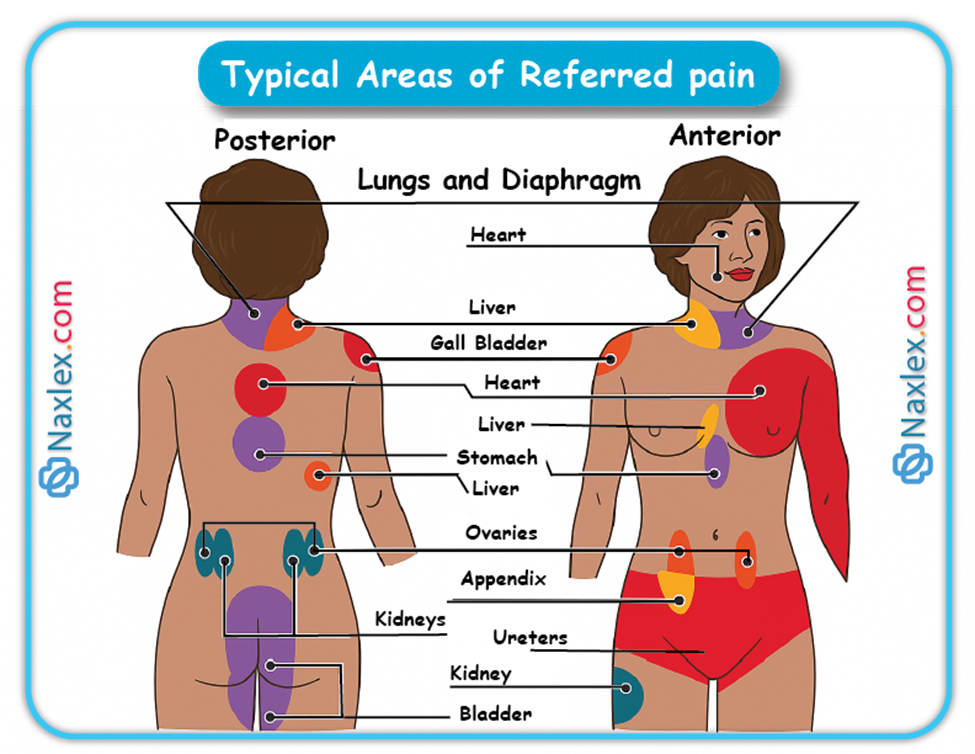

A patient with a myocardial infarction reports pain in their left shoulder and arm, but denies chest pain. This phenomenon is an example of:

Explanation

Pain in the left shoulder and arm during a myocardial infarction, without chest pain, is an example of referred pain. Referred pain occurs when pain is perceived at a location other than the site of the painful stimulus, due to shared nerve pathways in the spinal cord. In myocardial infarction, sensory nerve fibers from the heart and from the shoulder/arm enter the spinal cord at similar levels (T1–T4), causing the brain to misinterpret the pain’s origin.

Rationale for correct answer:

D. Referred pain: Results from convergence of visceral and somatic afferent fibers in the spinal cord, leading to the sensation of pain in an area distant from the affected organ.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

- Acute pain: While MI pain is acute in nature, this option does not explain the location mismatch between the pain and the injury.

- Chronic pain: Chronic pain lasts weeks to months; MI pain is sudden and short-term unless complications occur.

- Neuropathic pain: Caused by nerve injury or dysfunction, often described as burning or tingling; MI pain results from ischemia, not nerve damage.

Take home points

- Referred pain is due to shared neural pathways between visceral organs and somatic structures.

- Myocardial infarction often presents with referred pain to the jaw, neck, shoulder, or arm.

- Recognizing atypical pain patterns is crucial for early MI diagnosis and treatment.

Select all the characteristics that are typically associated with neuropathic pain. Select all that apply

Explanation

Neuropathic pain results from injury or dysfunction of the peripheral nerves or central nervous system, leading to abnormal pain signaling. Patients often describe it as burning, shooting, stabbing, or tingling. Common causes include shingles (postherpetic neuralgia), diabetic neuropathy, spinal cord injury, and multiple sclerosis. Neuropathic pain tends to be chronic and may respond poorly to standard opioid analgesics, often requiring adjuvant medications such as anticonvulsants or antidepressants.

Rationale for correct answers:

A. It is caused by damage to the nerves or the central nervous system: Nerve injury or disease disrupts normal pain processing and generates abnormal signals. This is the fundamental mechanism behind neuropathic pain.

B. It is often described as a sharp, stabbing, or burning sensation: These sensory descriptors are characteristic of neuropathic pain syndromes. They help distinguish it from nociceptive pain.

D. It can be caused by conditions like shingles, diabetic neuropathy, or spinal cord injury: These conditions damage peripheral or central nerves, triggering persistent pain. The resulting nerve dysfunction alters how pain signals are generated and transmitted.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

C. It is typically a short-term, self-limiting pain: Neuropathic pain is usually chronic and persists long after the initial injury or illness. It rarely resolves without targeted treatment.

E. It responds well to standard opioid analgesics: Neuropathic pain often shows limited improvement with opioids. More effective management involves medications such as anticonvulsants and antidepressants.

Take home points

- Neuropathic pain stems from nerve injury or CNS dysfunction.

- Burning, stabbing, and shooting are hallmark descriptors.

- Often chronic and resistant to opioids; adjuvant drugs are key in management.

What is the primary characteristic that differentiates acute pain from chronic pain?

Explanation

Acute pain generally has a sudden onset, is linked to a specific injury or illness, and resolves as healing occurs. Chronic pain persists for longer periods, often beyond normal healing time, and may not have a clearly identifiable cause.

Rationale for correct answer:

B. Acute pain is typically associated with a known cause and has a limited duration, whereas chronic pain is persistent and often lacks a clear cause: Acute pain serves as a protective mechanism, warning the body of injury or disease. Chronic pain can continue for months or years, with or without ongoing tissue damage.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

A. Acute pain is always more severe than chronic pain: Pain severity is subjective and can vary widely in both acute and chronic cases. Chronic pain can be equally or more intense than acute pain.

C. Chronic pain can only be managed with surgical interventions: Many chronic pain cases are managed with medications, physical therapy, and psychological interventions, not surgery.

D. Acute pain is a psychological experience, while chronic pain is a physiological one: Both acute and chronic pain involve physiological and psychological components. Neither type is purely psychological.

Take home points

- Acute pain is short-term and linked to a clear cause; chronic pain is long-term and may not have an obvious source.

- Pain duration, rather than severity, is the main differentiator.

- Both types of pain require targeted assessment and treatment.

patient has cancer that has metastasized to the bone. The patient's pain is best described as:

Explanation

Bone metastases cause pain through stimulation of nociceptors in bone and surrounding soft tissues. This type of pain is typically localized, aching, and aggravated by movement, which are hallmarks of somatic pain.

Rationale for correct answer:

B. Somatic pain: Originates from skin, muscles, bones, or connective tissue and is usually well localized. In bone metastases, tumor growth irritates periosteal nerves, producing deep, aching discomfort.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

A. Visceral pain: Arises from internal organs and is often poorly localized, sometimes referred to distant sites, which does not match the presentation here.

C. Neuropathic pain: Results from nerve injury or dysfunction and is often described as burning, shooting, or tingling, unlike typical bone pain.

D. Psychogenic pain: Refers to pain influenced primarily by psychological factors rather than direct tissue injury, which is not the case with metastatic bone involvement.

Take home points

- Somatic pain from bone metastases is usually well localized and aching.

- It results from activation of nociceptors in bone and soft tissue.

- Differentiating pain types guides appropriate management strategies.

Practice Exercise 3

A nurse is using the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) to assess a patient's pain. The patient rates their pain as a "10" on a scale of 0 to 10. The nurse understands that this number represents which dimension of the patient's pain?

Explanation

The Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) is used to measure the intensity of a patient’s pain, which reflects the sensory dimension. This dimension focuses on the physical aspects of pain, such as its intensity, location, and quality.

Rationale for correct answer:

B. Sensory dimension: Relates to the physiological detection and description of pain, including its intensity, timing, and location. The NRS score is a direct representation of perceived pain severity.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

A. Behavioral dimension: Involves observable actions like grimacing, guarding, or restlessness, which are not measured by the NRS.

C. Affective dimension: Refers to emotional responses to pain, such as fear, anxiety, or depression, rather than numerical intensity.

D. Cognitive dimension: Concerns beliefs, attitudes, and expectations about pain, which are not directly quantified by a numeric score.

Take home points

- The NRS measures pain intensity, a sensory characteristic.

- Sensory dimension assessment focuses on physical attributes of pain.

- Multiple dimensions of pain should be assessed for comprehensive care.

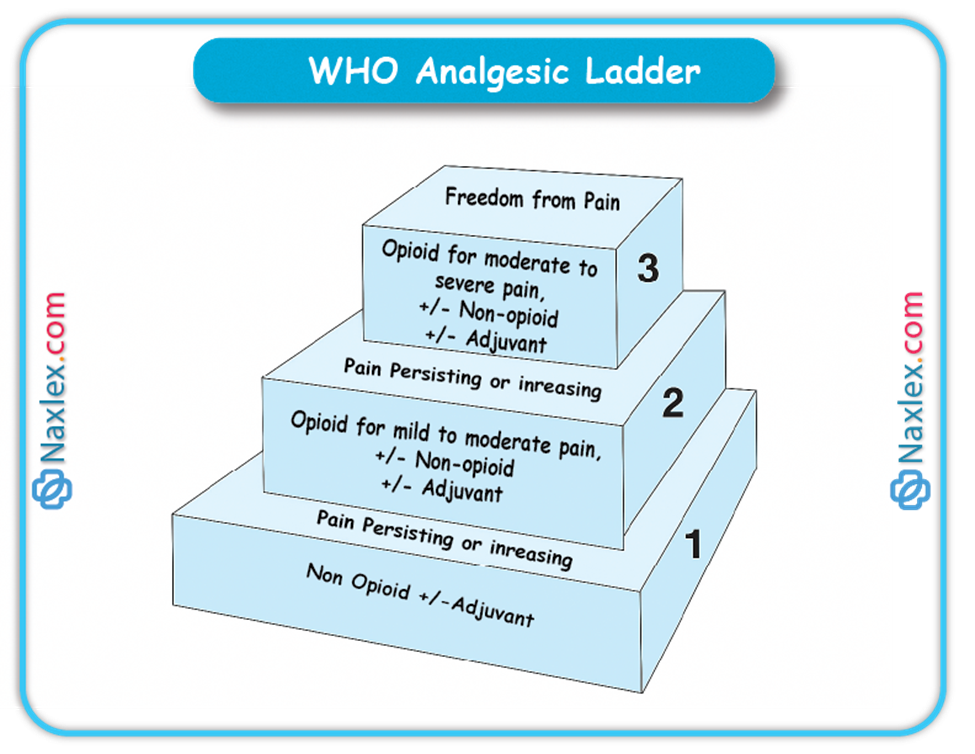

B. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) pain ladder, which of the following statements are correct regarding the management of cancer pain? Select all that apply

Explanation

The WHO pain ladder is a stepwise approach to managing cancer pain, beginning with non-opioids for mild pain, adding weak opioids for moderate pain, and progressing to strong opioids for severe pain. Adjuvant medications can be used at any step to enhance analgesia or manage specific pain types, such as neuropathic pain. The goal is adequate pain control, not necessarily moving down to lower steps.

Rationale for correct answers:

A. The first step is to use non-opioid analgesics, such as NSAIDs, for mild pain: Non-opioids are the foundation for managing early-stage or mild cancer pain. They are often combined with adjuvants as needed.

B. Weak opioids, like codeine, are added to the non-opioids for moderate pain: This combination enhances analgesia while maintaining non-opioid benefits. It represents step two of the ladder.

D. Adjuvants, like antidepressants or anticonvulsants, can be used at any step of the ladder: These agents target specific pain mechanisms and can complement opioids or non-opioids at any stage.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

C. Strong opioids, such as morphine or fentanyl, are used alone for severe pain: Strong opioids are typically combined with non-opioids and adjuvants for optimal pain relief, not used alone.

E. The goal is to move down the ladder to the lowest possible level of analgesic: The aim is consistent pain control and quality of life, not necessarily de-escalation of therapy.

Take home points

- WHO pain ladder progresses from non-opioids to weak opioids to strong opioids.

- Adjuvants can be used at any step to target specific pain mechanisms.

- The primary goal is effective, sustained pain relief, not stepping down therapy.

A patient reports sharp, stabbing pain after an abdominal surgery. What is the most appropriate initial action for the nurse to take?

Explanation

Before initiating pain management interventions, the nurse must assess the pain thoroughly using the patient’s description and a validated pain scale. This ensures that treatment decisions are based on accurate, individualized assessment data.

Rationale for correct answer:

C. Ask the patient to describe the pain and use a validated pain scale: A complete pain assessment includes location, quality, intensity, duration, and aggravating or relieving factors. Using a pain scale provides an objective measure to guide treatment and monitor effectiveness.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

A. Administer a strong opioid immediately, as the pain is likely severe: Medication choice should be based on a comprehensive assessment, not assumption. Immediate opioid administration without assessment can lead to inappropriate dosing or missed underlying complications.

B. Document the pain as "acute" and wait one hour to reassess: Delaying intervention after surgery can prolong suffering and increase stress response; assessment should occur promptly.

D. Tell the patient that some pain is expected after surgery: While postoperative pain is common, dismissing the report without assessment undermines patient trust and can delay appropriate management.

Take home points

Pain management starts with a thorough assessment using the patient’s own report.

- Validated pain scales provide a consistent way to measure and monitor pain.

- Never assume severity or type of pain without assessment.

The principle of using multimodal analgesia in pain management involves which of the following? Select all that apply

Explanation

Multimodal analgesia involves combining medications and techniques that act on different pain pathways to achieve better pain relief with fewer side effects. This often includes both pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies, as well as combining systemic and local analgesics.

Rationale for correct answers:

A. Using a combination of different analgesics that work on different pain pathways: Targeting multiple mechanisms of pain enhances effectiveness and reduces the required dose of each drug, minimizing side effects.

C. Combining pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions: Physical therapy, relaxation techniques, and cognitive-behavioral strategies can complement medications for more comprehensive pain control.

E. Providing local anesthetics in conjunction with systemic analgesics: Regional blocks or local infiltration can reduce the need for high systemic doses and improve targeted pain relief.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

B. Administering a single, high-dose opioid to achieve pain relief: This approach increases the risk of side effects and dependence without addressing all pain mechanisms.

D. Using only non-opioid medications to avoid addiction: While minimizing opioids can be beneficial, multimodal analgesia focuses on combining methods, not excluding specific drug classes entirely.

Take home points

- Multimodal analgesia uses multiple agents and methods to target different pain pathways.

- Combining systemic, local, and non-drug strategies enhances pain relief and reduces side effects.

- This approach is widely recommended for both acute and chronic pain management.

A nurse is teaching a patient about non-pharmacological pain management techniques. Which of the following is the most appropriate example of a non-pharmacological intervention?

Explanation

Applying a heat pack is a non-pharmacological intervention that can relieve muscle tension, improve circulation, and promote comfort without the use of medications. Such methods are often used alongside pharmacological treatments for better overall pain control.

Rationale for correct answer:

- Applying a heat pack to a sore back: Heat therapy relaxes muscles, increases blood flow, and can reduce pain perception. It is a safe, accessible, and effective non-drug approach for many types of musculoskeletal pain.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

B. Administering a PRN oral opioid: This is a pharmacological intervention involving medication, not a non-drug technique.

C. Giving a steroid injection to an inflamed joint: This involves a pharmacological agent delivered through injection, making it a drug-based treatment.

D. Increasing the patient's fluid intake: While hydration is important for overall health, it is not a recognized non-pharmacological pain management method.

Take home points

- Non-pharmacological interventions aim to relieve pain without medications.

- Heat therapy, cold packs, massage, and relaxation techniques are common examples.

- These methods are most effective when combined with appropriate pharmacological strategies.

Comprehensive questions

A nurse is teaching a group of students about pain. The students demonstrate understanding if they describe pain as:

Explanation

Pain is defined as an unpleasant, subjective sensory and emotional experience that may or may not be associated with tissue damage. According to the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), pain is always what the person experiencing it says it is. Because of its subjective nature, pain assessment relies on the client's self-report and should never be minimized or doubted based on observable cues alone.

Rationale for Correct Answer:

B. An unpleasant, subjective experience: This definition encompasses the sensory and emotional dimensions of pain, acknowledging that it is unique to the individual. It is consistent with the widely accepted IASP definition, recognizing that pain is influenced by past experiences, emotional state, and cultural background.

Rationale for Incorrect Answers:

A. A creation of a person’s imagination: This statement wrongly implies that pain is fabricated or not real. Such thinking can lead to inadequate pain management and patient mistrust.

C. A maladaptive response to a stimulus: While chronic pain may become maladaptive, this does not apply to the general definition of pain. Pain is primarily a protective mechanism, especially in acute settings.

D. A neurologic event resulting from activation of nociceptors: This defines nociceptive pain specifically and excludes other types of pain, such as neuropathic or psychogenic pain. Therefore, it is too narrow to serve as a general definition.

Key Takeaways:

- Pain is a subjective, multidimensional experience that includes both sensory and emotional components.

- The most accurate and reliable indicator of pain is the client’s self-report.

- Pain should not be defined solely by its physical or neurologic components, as it may exist without observable injury.

A nurse is assessing a client with suspected neuropathic pain. Which descriptions are most consistent with this type of pain? Select all that apply

Explanation

Neuropathic pain arises from damage or dysfunction in the nervous system, rather than from direct tissue injury. It is often described using distinctive sensory terms that reflect abnormal nerve signaling. Clients with neuropathic pain commonly report sensations that are burning, shooting, or electric shock-like. This type of pain may be chronic and difficult to treat with standard analgesics.

Rationale for Correct Answers:

B. Burning: A hallmark of neuropathic pain, often due to irritated or damaged nerves.

C. Shooting: Suggests pain that radiates or travels along a nerve pathway.

D. Shock-like: A classic description of sudden, stabbing nerve pain often seen in neuropathic conditions such as diabetic neuropathy or trigeminal neuralgia.

Rationale for Incorrect Answers:

A. Dull: This is more typical of nociceptive pain, such as that from musculoskeletal injury or visceral pain.

E. Mild: This describes pain intensity rather than quality. Neuropathic pain may be mild, but intensity alone is not a defining feature.

Key Takeaways:

- Neuropathic pain is often described as burning, shooting, or electric shock-like.

- It results from nerve injury or dysfunction, not from tissue damage alone.

- Descriptive terms help distinguish neuropathic from nociceptive pain and guide appropriate treatment.

A nurse is caring for a client with cancer who reports ongoing moderate pain with brief episodes of severe pain during dressing changes. The nurse anticipates that effective management includes:

Explanation

Clients with cancer pain often experience baseline persistent pain with breakthrough pain episodes. The most effective strategy involves long-acting opioids to manage continuous pain and short-acting opioids to control sudden, transient increases in pain, such as those during dressing changes. This approach provides consistent pain control while allowing flexibility to address unpredictable spikes in pain.

Rationale for Correct Answer:

C. A combination of long-acting and short-acting opioids: This is the standard of care for managing both persistent and breakthrough cancer pain. Long-acting opioids maintain a steady analgesic level, while short-acting opioids are used for intermittent severe pain episodes.

Rationale for Incorrect Answers:

A. Referral for surgical treatment of the pain: Surgical intervention is not a first-line approach for managing cancer-related pain unless the pain is caused by a reversible structural issue (e.g., tumor pressing on nerves). Pain control is typically achieved pharmacologically.

B. Regularly scheduled short-acting opioids plus acetaminophen: Short-acting opioids alone are not sufficient for sustained pain control. They may lead to peaks and troughs in pain relief, and the addition of acetaminophen does not address breakthrough pain effectively.

D. Assessment for exaggeration or drug-seeking behavior: This undermines trust and is inappropriate, especially in clients with cancer-related pain, who often require escalating analgesia due to disease progression. Pain reports should be accepted as valid and managed accordingly.

Key Takeaways:

- Cancer pain is best managed with a combination of long-acting opioids for baseline pain and short-acting opioids for breakthrough pain.

- Breakthrough pain is common during procedures like dressing changes and requires preemptive short-acting analgesia.

- Nurses should trust clients’ pain reports and avoid stigmatizing assumptions such as drug-seeking behavior.

A nurse is using nonpharmacologic strategies to help a client manage pain. Which of the following is an example of distraction?

Explanation

Distraction is a nonpharmacologic pain management technique that shifts the client’s attention away from the pain and onto something more pleasant or engaging. This can reduce the perception of pain by altering how the brain processes pain signals. Music therapy is a common and effective form of distraction used in various settings, including postoperative care, cancer treatment, and labor.

Rationale for Correct Answer:

B. Music: Listening to music engages auditory and cognitive attention, diverting focus from pain. It is widely used as a distraction technique and has been shown to reduce perceived pain and anxiety in many clinical populations.

Rationale for Incorrect Answers:

A. TENS (Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation): This method uses electrical impulses to stimulate nerves and block pain signals. It is a physical pain modulation method, not a distraction technique.

C. Exercise: While physical activity can promote the release of endorphins and improve function, it is not considered a form of distraction in pain management.

D. Biofeedback: This technique involves learning to control physiological responses using monitoring devices. It is a form of cognitive-behavioral therapy, not distraction.

Key Takeaways:

- Distraction works by redirecting attention away from pain to reduce pain perception.

- Music is a widely accepted and evidence-based distraction technique.

- Methods like TENS, biofeedback, and exercise help manage pain through mechanisms other than distraction.

A nurse is caring for a terminally ill client experiencing moderate to severe pain. Providing opioids in this situation:

Explanation

Administering opioids to a terminally ill client with moderate to severe pain is both appropriate and ethical. At the end of life, the priority is comfort and pain relief, not concerns about long-term side effects such as addiction. Opioids are effective and commonly used to manage cancer pain and palliative symptoms, improving the quality of the client’s remaining life.

Rationale for Correct Answer:

C. Is an appropriate nursing action: Providing opioids for pain control is consistent with palliative and hospice care goals. Nurses play a vital role in relieving suffering and promoting dignity during the dying process.

Rationale for Incorrect Answers:

A. May cause addiction: In terminal care, addiction is not a concern. The focus is on adequate symptom management and comfort.

B. Will probably be ineffective: Opioids are among the most effective agents for managing moderate to severe pain, especially in cancer or end-of-life scenarios.

D. Will likely hasten the client’s death: When used correctly and titrated to pain, opioids do not hasten death. This myth is a common barrier to effective pain management.

Key Takeaways:

- Opioid use in terminally ill clients is safe, appropriate, and essential for comfort.

- Concerns about addiction or hastening death should not interfere with adequate pain control.

- The nurse’s role includes advocating for and administering pain relief in alignment with palliative care goals.

A client arrives at the emergency department reporting sudden onset of severe upper abdominal pain. The client states that the pain began a few hours ago and has not improved. The nurse observes the client curled in a fetal position and rocking back and forth. Which action would best assist the nurse in further assessing the client’s pain?

Explanation

The most appropriate initial action when assessing pain is to ask the client to rate the pain using a standardized scale, such as 0 to 10, where 0 means no pain and 10 means the worst pain imaginable. This helps the nurse quantify the client's subjective experience, determine the urgency of intervention, and evaluate response to treatment over time.

Rationale for Correct Answer:

A. Ask the client to rate the pain on a scale from 0 to 10: This method provides an objective measurement of the client’s subjective experience of pain, forming the basis for treatment planning and evaluation. It is a standard and validated assessment tool.

Rationale for Incorrect Answers:

B. Determine if the client can stop moving about: This may offer indirect information but does not provide a reliable or quantifiable assessment of pain intensity.

C. Administer the prescribed pain medication: Pain must be assessed and documented before administration, especially if it's the first dose or if the provider needs data to determine dosage.

D. Observe if the client is breathing heavily: While observing physiologic signs of distress is helpful, subjective reporting is the most accurate and essential component of pain assessment.

Key Takeaways:

- The 0–10 numeric pain rating scale is a reliable tool for assessing pain severity.

- Subjective reporting is the gold standard in pain assessment.

- Objective observations support but do not replace the client’s verbal pain report.

A client with metastatic pancreatic cancer has an advance directive declining aggressive treatment and is receiving hospice care. A prescription is in place for pain medication every 3 to 4 hours as needed. What is the most appropriate action by the hospice nurse to ensure maximum comfort?

Explanation

In hospice care, the primary goal is to maximize comfort and relieve suffering. When a client has moderate to severe pain or a condition likely to cause ongoing pain such as metastatic pancreatic cancer, it is most appropriate to administer prescribed analgesics on a regular schedule rather than waiting for the client to request them. Giving pain medication every 3 hours (at the shorter end of the PRN range) provides consistent pain relief and prevents escalation of symptoms.

Rationale for Correct Answer:

A. Administer the medication every 3 hours: This proactive approach ensures optimal pain control by maintaining therapeutic levels of analgesia and minimizing breakthrough pain episodes, especially in terminally ill clients with progressive disease.

Rationale for Incorrect Answers:

B. Request a higher dose of pain medication: This may be necessary if current dosing is inadequate, but there is no evidence provided that the existing dose is ineffective. First, administer the prescribed dose at optimal intervals.

C. Give the medication only upon the client’s request: Clients may delay reporting pain due to stoicism, fear of addiction, or cognitive decline. Waiting for them to request it may lead to uncontrolled pain.

D. Wait until the client reports severe pain: This approach is reactive, not preventive. Severe pain is harder to manage and may reduce the client's quality of life.

Key Takeaways:

- Scheduled pain medication improves comfort in hospice care, especially for ongoing or expected pain.

- Preventing pain is more effective than treating it after it becomes severe.

- Hospice care emphasizes proactive, compassionate pain management aligned with the client's end-of-life goals.

A client with chronic back pain is scheduled to begin transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) therapy. The nurse explains that the electrical sensation produced by the TENS unit will most likely feel like:

Explanation

TENS therapy is a noninvasive method of pain control that uses low-voltage electrical currents delivered through electrodes placed on the skin. The most commonly reported sensation during TENS use is a pleasant tingling or buzzing feeling, which stimulates sensory nerves and helps block or reduce the perception of pain. The intensity can be adjusted to maintain comfort and effectiveness.

Rationale for Correct Answer:

C. A pleasant tingling sensation: This is the expected and desired sensation during TENS therapy. It should not be painful. The tingling distracts the nervous system from transmitting pain signals, providing relief for chronic or localized pain.

Rationale for Incorrect Answers:

A. A hard knocking feeling: This is not a typical or desired sensation with TENS. Such a sensation could indicate the intensity is too high or the electrode placement is inappropriate.

B. An intermittent burning reaction: A burning feeling is abnormal and may signal skin irritation, improper settings, or electrode malfunction. It should be reported and addressed immediately.

D. A small shock to the affected area: TENS does not deliver shocks. A shock-like feeling may indicate the intensity is set too high or the device is malfunctioning.

Key Takeaways:

- TENS therapy produces a pleasant tingling sensation, not pain or shocks.

- The goal of TENS is to modulate pain perception through gentle electrical stimulation.

- Any discomfort, burning, or shocking sensation should be evaluated and may require adjustment of settings or electrode placement.

A client with trigeminal neuralgia reports moderate to severe burning and shooting pain. In assisting the client with pain management, the nurse recognizes which of the following?

Explanation

Trigeminal neuralgia is a chronic neuropathic pain disorder characterized by sudden, burning or shooting facial pain, often triggered by light touch or facial movement. This type of pain responds poorly to traditional analgesics like NSAIDs and opioids. Instead, it is most effectively managed with adjuvant analgesics such as anticonvulsants (e.g., carbamazepine, gabapentin) and sometimes tricyclic antidepressants, which modulate nerve conduction and reduce neuropathic pain.

Rationale for Correct Answer:

A. Treatment includes the use of adjuvant analgesics: First-line pharmacologic management for trigeminal neuralgia involves adjuvant drugs that stabilize nerve activity. Anticonvulsants are the mainstay of therapy and provide significant pain relief for many clients.

Rationale for Incorrect Answers:

B. The pain will be chronic and require long-term treatment: While this is often true, it is not the best answer because it does not directly address the nurse’s role in assisting with pain management or identify the specific treatment approach.

C. The pain responds well to around-the-clock moderate doses of oral opioids: Neuropathic pain from trigeminal neuralgia generally responds poorly to opioids, which are not considered first-line treatments.

D. Pain can be controlled effectively with salicylates or NSAIDs: These drugs are typically ineffective for neuropathic pain and do not target the underlying nerve dysfunction seen in trigeminal neuralgia.

Key Takeaways:

- Trigeminal neuralgia is a neuropathic pain disorder that responds best to adjuvant analgesics such as anticonvulsants.

- Opioids and NSAIDs are generally ineffective for this type of pain.

- Nursing care focuses on medication education, pain management support, and helping clients avoid triggers that worsen the pain.

A nurse is teaching a group of students about pain transmission. Which interventions are effective during the transduction phase of the pain process? Select all that apply

Explanation

Transduction is the first phase of the pain process, during which noxious stimuli (mechanical, thermal, or chemical) are converted into electrical signals at the level of the peripheral nerve endings. This phase involves the release of inflammatory chemicals such as prostaglandins, bradykinin, and substance P, which sensitize nociceptors and initiate the pain signal. Interventions that block or reduce chemical mediators are most effective during this phase.

Rationale for Correct Answers:

B. Corticosteroids: These reduce inflammation and inhibit the production of prostaglandins and other inflammatory mediators, interfering with pain signal initiation.

D. Local anesthetics: They block sodium channels in nerve endings, preventing the generation of action potentials, and therefore block transduction.

E. Antiseizure medications: Some antiseizure medications (like gabapentin or pregabalin) modulate calcium channels and reduce excitability of nociceptors.

F. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): NSAIDs inhibit cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, reducing prostaglandin synthesis and decreasing peripheral nociceptor sensitization during transduction.

Rationale for Incorrect Answers:

A. Distraction: This affects the perception phase of pain, which occurs at the cortical level in the brain, not during transduction.

C. Epidural opioids: These target modulation and transmission of pain at the spinal cord level, not at the peripheral site of injury.

Key Takeaways:

- The transduction phase involves the conversion of painful stimuli into electrical signals at peripheral nerves.

- NSAIDs, corticosteroids, and local anesthetics are most effective during this phase.

- Interventions such as distraction, opioids, and antiseizure medications act at later stages of the pain process.

A client with chronic pain reports that oral morphine is no longer effective for pain control. Which medication would the nurse expect the provider to prescribe to achieve improved pain relief?

Explanation

Duragesic is the brand name for fentanyl transdermal patches, which deliver potent, long-acting opioid analgesia through the skin. Fentanyl is significantly stronger than morphine, making it an appropriate alternative for clients with chronic pain who have developed tolerance to oral morphine. The patch provides continuous pain relief over 72 hours, making it ideal for clients who require stable, round-the-clock opioid therapy.

Rationale for Correct Answer:

A. Duragesic: Fentanyl patches are used for clients who are opioid-tolerant and need long-term, continuous pain control. It bypasses the GI tract and provides consistent systemic analgesia, which is beneficial when oral opioids become ineffective.

Rationale for Incorrect Answers:

B. Oramorph SR: This is a sustained-release formulation of morphine, similar to what the client is already using. If morphine is no longer effective, increasing the dose or continuing the same drug in a different form is unlikely to help.

C. Hydrocodone: Hydrocodone is less potent than morphine. Switching from morphine to hydrocodone would likely reduce pain control rather than improve it.

D. Intranasal butorphanol (Stadol): Butorphanol is a mixed agonist-antagonist opioid. It can precipitate withdrawal and reduce pain relief in clients already taking full opioid agonists like morphine, making it inappropriate for this scenario.

Key Takeaways:

- Fentanyl (Duragesic) is appropriate for clients with chronic pain and opioid tolerance.

- Changing to a stronger opioid is often necessary when current opioids become ineffective.

- Mixed agonist-antagonists like butorphanol should be avoided in clients taking full opioid agonists due to the risk of withdrawal and decreased analgesia.

A nurse is monitoring a client who is receiving opioid analgesia. Which of the following adverse effects should the nurse anticipate? Select all that apply

Explanation

Opioid analgesics are effective for moderate to severe pain but are associated with a variety of adverse effects, particularly involving the central nervous system and gastrointestinal system. Nurses must monitor for these expected reactions to ensure prompt recognition and intervention.

Rationale for Correct Answers:

C. Bradypnea: Opioids depress the respiratory center in the brainstem, which can lead to respiratory depression, especially at higher doses or in opioid-naïve clients.

D. Orthostatic hypotension: Opioids can cause vasodilation and reduced sympathetic tone, leading to a drop in blood pressure when changing positions.

E. Nausea: A common early side effect, nausea occurs due to opioid stimulation of the chemoreceptor trigger zone in the brain.

Rationale for Incorrect Answers:

A. Urinary incontinence: Opioids more commonly cause urinary retention, not incontinence, due to increased sphincter tone and decreased bladder contractility.

B. Diarrhea: Opioids cause constipation, not diarrhea, by slowing gastrointestinal motility through action on opioid receptors in the gut.

Key Takeaways:

- Common adverse effects of opioids include bradypnea, orthostatic hypotension, nausea, constipation, and urinary retention.

- Respiratory depression is the most serious side effect and requires immediate attention.

- Nurses must monitor vital signs, GI status, and bladder function closely during opioid therapy.

A nurse is caring for a client who is receiving morphine via a patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) infusion device after abdominal surgery. Which of the following statements by the client indicates correct understanding of the PCA device?

Explanation

Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) is a method that allows clients to self-administer small doses of opioid medication to manage pain. It provides a safe, controlled, and timely approach to pain relief. It is essential that clients understand how to use the PCA appropriately and recognize when to notify the nurse if the pain is not being effectively controlled.

Rationale for Correct Answer:

C. “I should tell the nurse if the pain doesn’t stop after I use this device.”: This shows appropriate understanding that PCA is intended to relieve pain, and persistent pain may require dose adjustment or reassessment by the healthcare team.

Rationale for Incorrect Answers:

A. “I’ll wait to use the device until it’s absolutely necessary.”: PCA works best when used early and consistently at the onset of pain. Waiting until pain becomes severe makes it harder to control.

B. “I’ll be careful about pushing the button so I don’t get an overdose.”: PCA devices have built-in safety limits (lockout intervals) to prevent overdose. This statement reflects unnecessary fear that may lead to underuse.

D. “I will ask my son to push the dose button when I am sleeping.”: This is unsafe and contraindicated. Only the client should activate the PCA to prevent oversedation or respiratory depression, a practice known as “PCA by proxy” is never appropriate.

Key Takeaways:

- Clients should notify the nurse if PCA is not relieving pain adequately.

- Only the client should press the PCA button to ensure safe use.

- PCA should be used proactively, not delayed until pain becomes severe.

A nurse is obtaining a history from a client who reports pain. What principle should guide the nurse’s assessment?

Explanation

The most fundamental principle of pain assessment is that pain is a subjective experience. According to the American Pain Society and the International Association for the Study of Pain, pain is whatever the person experiencing it says it is, existing whenever they say it does. This means the nurse must prioritize the client’s self-report over objective data or assumptions.

Rationale for Correct Answer:

D. Pain is whatever the client says it is: This principle recognizes the subjective nature of pain. The client’s verbal report is the most reliable indicator of pain, regardless of whether it correlates with clinical findings or vital signs.

Rationale for Incorrect Answers:

A. Some clients exaggerate their level of pain: This reflects a biased assumption that undermines trust and can lead to inadequate pain management. Nurses must believe and validate all reports of pain.

B. Pain must have an identifiable source to justify opioid use: Not all pain has a visible or measurable cause (e.g., neuropathic or psychogenic pain), and opioid use should be based on pain severity and response to other treatments, not just diagnostic findings.

C. Objective data are essential in assessing pain: While objective indicators (e.g., facial grimacing, vital sign changes) can support assessment, they are not required for pain to be real or treated appropriately.

Key Takeaways:

- Client self-report is the gold standard for pain assessment.

- Pain can exist without objective findings or a clear physiological source.

- Nurses must approach pain assessment with nonjudgmental acceptance and validation.

A nurse is assessing the pain level of a client who presents to the emergency department with severe abdominal pain. The nurse asks whether the client has experienced nausea or vomiting. The nurse is assessing which of the following?

Explanation

When assessing pain, it is important to evaluate associated symptoms that may accompany or result from the pain, such as nausea, vomiting, dizziness, or sweating. These symptoms provide contextual information that can help in determining the underlying cause, severity, and impact of the pain on the client’s functioning.

Rationale for Correct Answer:

A. Presence of associated symptoms: Asking about nausea or vomiting is an assessment of symptoms that occur alongside the pain, which may help in identifying the source (e.g., gastrointestinal, renal, or infectious origin) and guide further diagnostic or therapeutic interventions.

Rationale for Incorrect Answers:

B. Location of the pain: This involves asking where the pain is felt, which is not addressed by inquiring about nausea or vomiting.

C. Pain quality: Pain quality refers to the character of the pain, such as sharp, burning, cramping, or dull. Nausea or vomiting does not describe the pain itself.

D. Aggravating and relieving factors: These involve identifying what worsens or eases the pain, such as movement, eating, or positioning and not associated symptoms.

Key Takeaways:

- Associated symptoms like nausea and vomiting provide important information about the context and cause of pain.

- A comprehensive pain assessment includes location, quality, severity, timing, associated symptoms, and triggers.

- Evaluating associated symptoms helps guide accurate diagnosis and effective treatment.

Exams on Pain

Custom Exams

Login to Create a Quiz

Click here to loginLessons

Naxlex

Just Now

Naxlex

Just Now

- Objectives

- Introduction to Pain Management

- Practice Exericise 1

- Pain Transmission (Nociception)

- Central Sensitization and Neuroplasticity

- Referred Pain

- Classification of pain

- Practice Exercise 2

- Pain assessment

- Management of pain

- Nursing and collaborative management

- Challenges to Effective Pain Management

- Ethical issues in pain management

- Managing pain in special populations

- Practice Exercise 3

- Summary

- Comprehensive questions

Notes Highlighting is available once you sign in. Login Here.

Objectives

- Differentiate between the four neural mechanisms of pain: transduction, transmission, perception, and modulation.

- Compare and contrast the characteristics, causes, and treatment approaches for nociceptive (superficial somatic, deep somatic, and visceral) and neuropathic (central, peripheral, deafferentation, and sympathetically maintained) pain.

- Analyze subjective and objective data from a pain assessment to formulate a comprehensive understanding of a patient's pain experience.

- Formulate an interdisciplinary pain management plan that incorporates both pharmacological (nonopioid, opioid, adjuvant) and nonpharmacological (cutaneous stimulation, distraction, relaxation, imagery, acupuncture, environmental modifications, extremity elevation) interventions.

- Develop a teaching plan for patients and caregivers addressing effective self-management techniques, realistic pain control goals, potential side effects of therapies, and the importance of reporting unrelieved pain.

- Explain the differences between tolerance, physical dependence, pseudoaddiction, and addiction in the context of opioid therapy, and describe appropriate nursing responses to each.

- Discuss the ethical principles, including the rule of double effect, relevant to pain management, particularly concerning the fear of hastening death and the use of placebos.

- Adapt pain assessment and management strategies for special populations, specifically nonverbal patients and those with substance abuse problems.

Introduction to Pain Management

Effective pain management is a cornerstone of patient care, aiming to alleviate suffering and improve quality of life. This comprehensive overview explores the multifaceted nature of pain, from its underlying physiological mechanisms to its assessment, various management strategies, and the ethical considerations involved. It highlights the critical role of nurses within an interdisciplinary team, emphasizing patient-centered care and effective communication to overcome common challenges and misconceptions associated with pain.

McCaffery's and IASP Definitions

In 1968, Margo McCaffery, a nurse and pioneer in pain management, defined pain as:

“Whatever the person experiencing the pain says it is, existing whenever the person says it does.”

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines pain as:

“An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage.”

These definitions highlight pain’s subjective nature, emphasizing that the client’s self-report is the most valid measure of pain. This becomes complex when caring for nonverbal patients (e.g., comatose individuals, infants, or those with dementia), where behavioral and physiological cues must guide assessment.

Pain is multidimensional, affecting the individual on multiple levels:

|

Dimension |

Description |

|

Physiologic |

Genetic, anatomical, and physical factors influence how noxious stimuli are recognized and processed. |

|

Affective |

Emotional responses such as fear, anger, anxiety, and depression can heighten pain perception and reduce quality of life. |

|

Cognitive |

Beliefs, memories, and attitudes shape a person’s understanding and reaction to pain. Catastrophizing (e.g., “My pain will never end”) worsens outcomes. |

|

Behavioral |

Observable expressions (e.g., grimacing, restlessness) may indicate pain; used especially in nonverbal clients. |

|

Sociocultural |

Culture, gender, and social support influence how pain is perceived, reported, and managed. Expectations, stigma, and family roles play a role. |

|

Men |

Women |

|

Less likely to report pain |

More frequent reports of chronic pain |

|

Report more control over pain |

More likely to experience migraine, IBS, fibromyalgia, arthritis |

|

Less likely to use alternative pain therapies |

Often under-medicated for chest/abdominal pain |

|

Greater pain tolerance |

Experience greater pain sensitivity even with same conditions |

Consequences of Unrelieved Acute Pain

|

System |

Potential Effects |

|

Endocrine/Metabolic |

↑ Cortisol, ACTH, catecholamines → hyperglycemia, catabolism, insulin resistance |

|

Cardiovascular |

↑ HR, ↑ BP, ↑ coagulability → angina, MI, DVT |

|

Respiratory |

↓ Tidal volume, ↓ cough → atelectasis, pneumonia |

|

Renal |

↓ Output, fluid retention → electrolyte imbalance |

|

GI |

↓ Motility → constipation, ileus, anorexia |

|

Musculoskeletal |

Muscle spasm, fatigue, immobility |

|

Neurologic |

Confusion, poor cognition |

|

Immune |

↓ Immunity → infection risk |

Pain Transmission (Nociception)

Nociception is the neurophysiological process by which tissue damage is detected and interpreted as pain by the nervous system. It involves four distinct phases: transduction, transmission, perception, and modulation

Transduction is the initial step where a noxious (tissue-damaging) stimulus is converted into an electrical signal, known as an action potential.

- What happens: When tissues are damaged by mechanical (e.g., surgical incision), thermal (e.g., sunburn), or chemical (e.g., toxic substances) stimuli, various chemicals are released into the injured area. These include:

- Hydrogen ions

- Substance P

- Adenosine triphosphate (ATP)

- Serotonin

- Histamine

- Bradykinin

- Prostaglandins

- Interleukins

- Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)

- Role of Nociceptors: These chemicals activate nociceptors, which are specialized receptors or free nerve endings. Once activated, nociceptors generate an action potential that travels to the spinal cord.

Transmission is the process of relaying these pain signals from the periphery (injury site) to the spinal cord and then to the brain.

- Peripheral Nerve Fibers: Pain impulses are carried by primary afferent fibers, specifically:

- A-delta fibers: Small, myelinated fibers that conduct pain rapidly, responsible for initial, sharp pain.

- C fibers: Small, unmyelinated fibers that transmit pain more slowly, producing a dull, aching, or throbbing sensation.

- These fibers extend directly from the injury site to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord without synapsing.

- Dorsal Horn Processing: Upon reaching the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, the nociceptive signal is processed.

- Neurotransmitters: Released from afferent fibers, these bind to receptors on nearby cells. Some (e.g., glutamate, aspartate, substance P) activate cells, while others (e.g., GABA, serotonin, norepinephrine) inhibit activation.

- Opioid Involvement: Both exogenous (e.g., morphine) and endogenous (e.g., enkephalin, β-endorphin) opioids bind to opioid receptors in this area, blocking neurotransmitter release (especially substance P) and producing analgesic effects.

- Transmission to Thalamus and Cortex: From the dorsal horn, the signal is communicated to third-order neurons, primarily in the thalamus, and then to various regions of the cerebral cortex where pain is perceived. Pathways involved include the spinothalamic and spinoreticular tracts.

- Therapeutic Interventions: Medications like opioid analgesics and baclofen work by affecting transmission in these pathways.

- Dermatomes: The way nerve fibers enter the spinal cord relates to dermatomes, which are specific areas of skin innervated by a single spinal cord segment. This explains patterns of pain or rashes (e.g., shingles).

Perception is when the individual becomes consciously aware of pain, recognizing it, defining it, and assigning it meaning.

- Brain Structures: There isn't one specific pain center; instead, several brain structures are involved:

- Reticular Activating System (RAS): Warns the individual to attend to the pain.

- Somatosensory System: Responsible for localizing and characterizing the pain.

- Limbic System: Involved in emotional and behavioral responses to pain.

- Cortical Structures: Crucial for constructing the meaning of the pain.

- Impact of Perception: Understanding this allows for effective pain management strategies like distraction and relaxation, which can reduce the sensory and emotional components of pain. Opioids, antiseizure drugs, and antidepressants also modify pain perception.

Modulation involves the activation of descending pathways from the brain that can either inhibit or facilitate the transmission of pain signals.

- Mechanism: These descending fibers release chemicals such as serotonin, norepinephrine, GABA, and endogenous opioids, which can inhibit pain transmission at various levels (periphery, spinal cord, brainstem, cerebral cortex).

- Therapeutic Interventions: Antidepressants like tricyclic antidepressants and SNRIs interfere with the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine, increasing their availability to inhibit noxious stimuli, making them useful in chronic pain management.

Referred Pain

Referred pain is pain perceived at a location distant from the actual site of the painful stimulus. This is important to consider when evaluating pain, especially concerning visceral organs, as misinterpreting its location can lead to incorrect diagnoses and treatments. For example, liver pain might be felt in the neck or flank, not just the abdomen.

Typical Areas of Referred pain

Classification of pain

Pain can be categorized in several ways. Most commonly, pain is categorized as nociceptive or neuropathic based on underlying pathology. Another useful scheme is to classify pain as acute or chronic.

Classification by Underlying Pathology

This classification focuses on how the pain signals are generated and processed in the nervous system.

Definition: This type of pain results from the normal processing of stimuli that damage normal tissue, or have the potential to do so if prolonged. It's essentially the body's warning system for actual or potential tissue injury.

Treatment: Generally responds well to both non-opioid and opioid medications.

Types of Nociceptive Pain:

- Superficial Somatic Pain:

- Origin: Skin, mucous membranes, and subcutaneous tissue.

- Characteristics: Tends to be well-localized, often described as sharp, burning, or prickly.

- Examples: Sunburn, skin contusions.

- Deep Somatic Pain:

- Origin: Muscles, fasciae, bones, and tendons.

- Characteristics: Can be localized or diffuse and radiating, often described as deep, aching, or throbbing.

- Examples: Arthritis, tendonitis, myofascial pain.

- Visceral Pain:

- Origin: Internal organs (e.g., GI tract, bladder) and the lining of body cavities.

- Characteristics: Can be well or poorly localized, often referred to cutaneous (skin) sites. It responds to inflammation, stretching (like from a tumor or obstruction causing distention), and ischemia, producing intense cramping pain.

- Examples: Appendicitis, pancreatitis, cancer affecting internal organs, irritable bowel syndrome, surgical incision pain.

Definition: This pain arises from abnormal processing of sensory input by either the peripheral or central nervous system due to damage to nerves or CNS structures.

Treatment: Often not well-controlled by opioid analgesics alone. Treatment typically involves a multimodal approach including adjuvant analgesics like tricyclic antidepressants, SNRIs, antiseizure drugs (e.g., gabapentin, pregabalin), transdermal lidocaine, α2-adrenergic agonists, and sometimes NMDA receptor antagonists like ketamine.

Characteristics: It's frequently described as numbing, hot, burning, shooting, stabbing, sharp, or electric shock-like. It can be sudden, intense, short-lived, or lingering, often with paroxysmal (sudden, intense) firing of injured nerves. Patients might also experience numbness, allodynia (pain from non-painful stimuli), or changes in reflexes and motor strength. No single symptom is diagnostic.

Common Causes: Trauma, inflammation (e.g., from a herniated disc), metabolic diseases (e.g., diabetes mellitus), alcoholism, nervous system infections (e.g., herpes zoster, HIV), tumors, toxins, and neurological diseases (e.g., multiple sclerosis).

Types of Neuropathic Pain:

- Central Pain:

- Cause: Primary lesion or dysfunction in the central nervous system (CNS).

- Examples: Post-stroke pain, pain associated with multiple sclerosis.

- Peripheral Neuropathies:

- Cause: Damage to one or many peripheral nerves.

- Examples: Diabetic neuropathy, alcohol-nutritional neuropathy, trigeminal neuralgia, postherpetic neuralgia.

- Deafferentation Pain:

- Cause: Results from a loss of afferent (incoming) input due to peripheral nerve injury (e.g., amputation) or CNS damage (e.g., spinal cord injury).

- Examples: Phantom limb pain, post-mastectomy pain, spinal cord injury pain.

- Sympathetically Maintained Pain:

- Cause: Pain that persists due to dysregulation of the sympathetic nervous system activity.

- Examples: Phantom limb pain, complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS).

- Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS): A particularly debilitating type of neuropathic pain with dramatic changes in skin color and temperature, intense burning pain, skin sensitivity, sweating, and swelling.

- CRPS Type I: Often triggered by tissue injury, surgery, or a vascular event.

- CRPS Type II: Includes all features of Type I plus a peripheral nerve lesion.

- Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS): A particularly debilitating type of neuropathic pain with dramatic changes in skin color and temperature, intense burning pain, skin sensitivity, sweating, and swelling.

This classification helps differentiate between pain that is temporary and pain that has become a persistent condition.

Onset: Sudden.

Duration: Typically less than 3 months, or for as long as it takes for normal healing to occur.

Severity: Can range from mild to severe.

Cause: Usually a clearly identifiable precipitating event (e.g., illness, surgery, trauma, infection, acute ischemia).

Course: Generally decreases over time and resolves as recovery occurs.

Typical Manifestations: Often reflects sympathetic nervous system activation, such as increased heart rate, respiratory rate, and blood pressure; diaphoresis (sweating), pallor, anxiety, agitation, confusion, and urine retention.

Goals of Treatment: Pain control with eventual elimination, and treatment of the underlying cause (e.g., splinting a fracture, antibiotics for an infection).

Note: Acute pain that persists can lead to disabling chronic pain states through processes like central sensitization and neuroplasticity. Aggressive and effective treatment of acute pain is crucial to prevent the development of chronic pain.

Chronic Pain (Persistent Pain)

Onset: Can be gradual or sudden.

Duration: Lasts for longer periods, often defined as more than 3 months, or beyond the expected healing time for an acute injury.

Severity: Can range from mild to severe.

Cause: May not be known. The original cause of the pain might differ from the mechanisms that maintain the pain over time.

Course: Typically, the pain does not go away. It is characterized by periods of increasing and decreasing intensity.

Typical Manifestations: Predominantly behavioral manifestations, such as a flat affect, decreased physical activity, fatigue, and withdrawal from social interaction. Unlike acute pain, chronic pain does not appear to have an adaptive warning role.

Goals of Treatment: Pain control to the extent possible, with a primary focus on enhancing function and improving quality of life.

Pain assessment

Pain assessment is a crucial and often underestimated component of effective pain management. It involves a systematic approach to understanding a patient's pain experience to guide appropriate interventions.

Core Principles of Pain Assessment

Effective pain assessment is guided by fundamental principles:

- Patient's Right to Assessment and Management: All patients should be regularly screened for pain, and when present, a thorough assessment should be conducted.

- Pain is Subjective: The patient's self-report is the most reliable indicator of pain. Healthcare providers should accept and respect this report unless there are clear reasons for doubt.

- Physiological and Behavioral Signs are Not Reliable Alone: Objective signs like tachycardia or grimacing are not specific or reliable indicators of pain on their own. Do not rely primarily on these unless the patient cannot self-report.

- Pain is a Sensory and Emotional Experience: Assessment must address both the physical and psychological aspects of pain.

- Assessment Approaches Must Be Appropriate: Tools and methods should be tailored to the patient population, especially for those with communication difficulties. Involving family members is often appropriate.

- Pain Can Exist Without a Physical Cause: Do not attribute pain solely to psychological causes if a physical origin cannot be found.

- Individual Pain Response Varies: A uniform pain threshold does not exist; different patients experience different levels of pain from comparable stimuli.

- Chronic Pain Can Increase Sensitivity: Patients with chronic pain may be more sensitive to pain and other stimuli. Pain tolerance varies significantly among individuals due to factors like heredity, energy levels, coping skills, and prior experiences.

- Unrelieved Pain Has Adverse Consequences: Untreated acute pain can lead to physiological changes that increase the likelihood of developing persistent (chronic) pain. Patients should be encouraged to report pain, especially if they are reluctant or deny it.

Goals of a Nursing Pain Assessment

- Describe the Patient's Pain Experience: To identify and implement appropriate pain management techniques.

- Identify Patient's Goals and Resources: To establish goals for therapy and determine resources for self-management.

Elements of a Pain Assessment

A comprehensive pain assessment involves direct interview, observation, and complementary diagnostic and physical examination findings. The assessment should always be multidimensional, adapting to the clinical setting and patient.

Important Note: Patients may use words other than "pain" (e.g., "soreness," "aching"). Document their specific terms and consistently use those when asking about their pain.

Subjective Data

1. Pain Pattern:

- Onset:

- Acute Pain: Patients usually know precisely when it started (e.g., from injury, acute illness, surgery).

- Chronic Pain: Patients may have difficulty pinpointing the exact start time.

- Duration: How long the pain has lasted helps determine if it's acute or chronic and can guide diagnostic workups (e.g., new severe back pain in a cancer patient with chronic back pain could indicate new metastatic disease).

- Course:

- Constant (Around-the-clock) Pain: Pain is present all the time.

- Intermittent Pain: Periods of pain interspersed with pain-free periods.

- Breakthrough Pain (BTP): Transient, moderate to severe pain that occurs in patients whose baseline persistent pain is otherwise well-controlled. It can be predictable or unpredictable, typically peaking in 3-5 minutes and lasting up to 30 minutes or longer. Specific transmucosal fentanyl products are used for BTP.

- End-of-Dose Failure: Pain that occurs before the expected duration of a specific analgesic (e.g., increased pain after 48 hours on a 72-hour fentanyl patch). This indicates a need for dose or schedule adjustments, not BTP.

- Episodic, Procedural, or Incident Pain: A transient increase in pain triggered by a specific activity or event (e.g., dressing changes, movement, catheterization).

2. Location:

- Identifying the exact or general location(s) of pain is crucial for identifying causes and guiding treatment.

- Patients may describe specific sites, point to areas on their body, or mark areas on a pain map.

- Referred Pain: Pain perceived distant from its origin (e.g., myocardial infarction causing left shoulder pain). (Refer to FIG. 9-2).

- Radiating Pain: Pain that spreads from its origin to another site (e.g., angina pectoris radiating from the chest to the jaw or left arm; sciatica radiating down the leg).

- Document all pain locations, as many patients have multiple sites of pain.

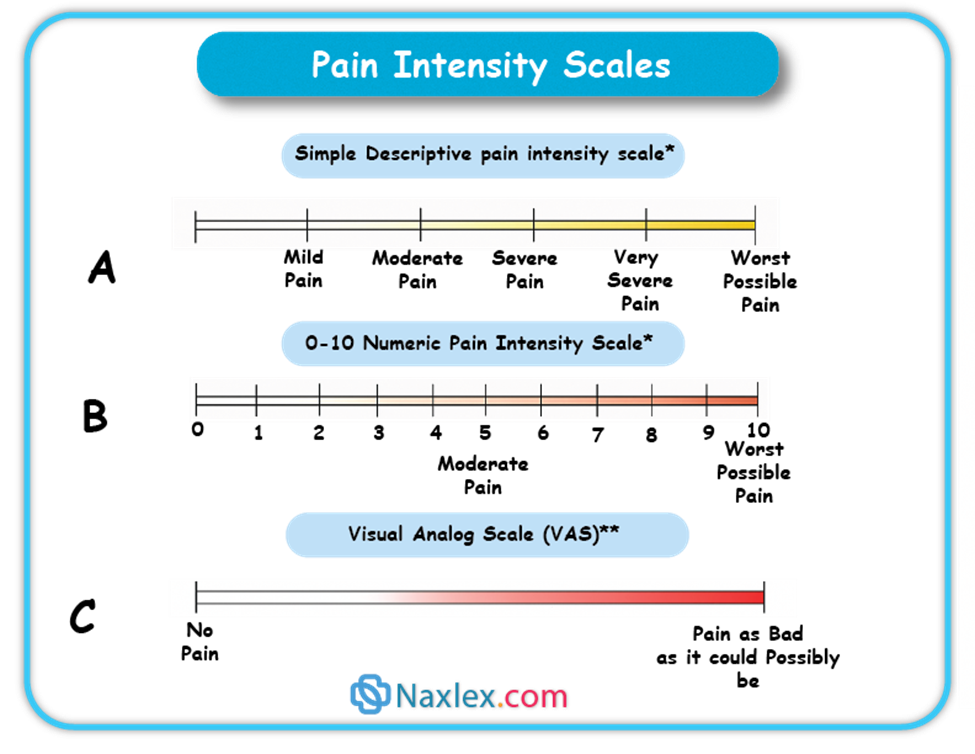

3. Intensity (Severity):

- A reliable measure for determining treatment type and effectiveness.

- Pain Scales: Help patients communicate intensity. Choice of scale should be based on developmental needs and cognitive status.

- Numeric Scales: 0 = no pain, 10 = worst pain.

- Verbal Descriptor Scales: None, a little, moderate, severe.

- Visual Scales: Pain Thermometer Scale (FIG. 9-3), Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale, FACES Pain Scale–Revised (useful for patients with cognitive or language barriers).

- Important Caution: Do not dose opioids solely based on reported pain scores. Balance pain relief with sedation level and respiratory status to ensure safe practice and minimize adverse events.

4. Quality:

- Refers to the nature or characteristics of the pain.

- Neuropathic Pain Descriptors: Burning, numbing, shooting, stabbing, electric shock-like, itchy.

- Nociceptive Pain Descriptors: Sharp, aching, throbbing, dull, cramping.

- These descriptors help classify the pain (e.g., neuropathic, nociceptive, visceral) and guide appropriate treatment options based on the underlying pain mechanism.

5. Associated Symptoms:

- Ask about symptoms that may exacerbate or be exacerbated by pain, such as anxiety, fatigue, and depression.

- Inquire about activities and situations that increase or alleviate pain (e.g., movement affecting musculoskeletal pain, resting decreasing pain). This helps characterize the pain and inform treatment choices.

6. Management Strategies:

- Ask patients what methods they are currently using to control pain, what they've used previously, and their outcomes.

- Include prescription and nonprescription drugs, and non-drug therapies (e.g., hot/cold applications, complementary therapies like acupuncture, relaxation techniques).

- Document both effective and ineffective strategies.

7. Impact of Pain:

- Assess how pain influences the patient's quality of life and functioning:

- Ability to sleep, enjoy life, interact with others.

- Performance of work and household duties.

- Engagement in physical and social activities.

- Impact on mood and emotional well-being.

8. Patient's Beliefs, Expectations, and Goals:

- Assess attitudes and beliefs that might hinder effective treatment (e.g., fear of opioid addiction).

- Ask about the patient's expectations and goals for pain management.

- In acute care settings, a more abbreviated assessment should still include effects on sleep, daily activities, relationships, physical activity, emotional well-being, pain descriptors, and coping strategies.

Objective Data

- Physical Examination: Includes evaluation of functional limitations.

- Psychosocial Evaluation: Includes assessment of mood.

- Diagnostic Studies: Complete the initial assessment.

Documentation

- Thorough documentation of the pain assessment is critical for effective communication among healthcare team members.

- Many facilities use specific tools for initial pain assessment, treatment, and reassessment.

- Examples of multidimensional pain assessment tools include the Brief Pain Inventory, McGill Pain Questionnaire, Memorial Pain Assessment Card, and Neuropathic Pain Scale.

Reassessment