Please set your exam date

Mobility

Study Questions

Practice Exercise 1

A patient performs rehabilitative exercises with resistance after a knee injury. The nurse interprets this type of exercise as which of the following?

Explanation

Different types of muscle contractions and exercise modalities are used in rehabilitation. Isotonic exercises change muscle length while moving a joint against a fixed load; isometric exercises create tension without movement; isokinetic exercises use machines that control movement speed and adjust resistance so muscle works maximally through the whole range - making them particularly useful for targeted rehab.

Rationale for correct answer:

2. Isokinetic exercise uses specialized equipment that provides resistance so that the muscle contracts at a constant speed throughout the range of motion. Isokinetic training is commonly used in rehabilitation (especially for knee injuries) because it allows controlled, measurable strengthening while protecting the joint.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Isotonic exercises produce movement of a joint while the muscle changes length (concentric/eccentric contractions) against a constant load (e.g., lifting free weights, doing squats). They build strength and endurance but the resistance is typically a fixed weight.

3. Isometric exercise involves muscle contraction without joint movement (no change in muscle length) - for example, pushing the palms together or holding a static quad set. It increases muscle tension and can maintain strength but does not produce the joint motion typical of many rehab programs.

4. Aerobic exercise is rhythmic, uses large muscle groups, and increases oxygen consumption and cardiovascular endurance (e.g., walking, cycling). It is not primarily focused on resisted, controlled strengthening of a single joint with a rehab device.

Take home points

- Isokinetic - rehab machines that keep contraction speed constant and automatically adjust resistance

- Excellent for controlled strengthening after joint injury.

- Isotonic- joint movement against set weights

- Isometric- tension without movement; aerobic -cardiovascular-focused.

Which of the following would the nurse expect to assess when a patient experiences a greater breakdown of protein than that which is manufactured?

Explanation

Protein contains nitrogen; the body’s nitrogen balance reflects whether it is building (positive balance) or breaking down (negative balance) lean tissue. Situations with increased catabolism (severe illness, injury, starvation) or insufficient dietary protein produce negative nitrogen balance - a clinical sign that the patient is losing lean body mass and needs nutritional and medical intervention.

Rationale for correct answer:

4. Negative nitrogen balance: Nitrogen balance compares nitrogen (protein) intake with nitrogen loss. When protein catabolism exceeds synthesis, more nitrogen is excreted than ingested, producing a negative nitrogen balance.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Fluid volume excess describes too much body water (edema, weight gain, bounding pulses) and is not a direct marker of protein catabolism versus synthesis.

2. A contracture is a permanent shortening of muscle or connective tissue around a joint from immobilization or fibrosis; it’s not the direct result of whole-body negative protein balance.

3. Osteoporosis is loss of bone mass and microarchitectural deterioration; while nutrition and protein affect bone health, the immediate physiologic shorthand for more protein breakdown than synthesis is not osteoporosis.

Take home points

- Negative nitrogen balance- more protein breakdown than synthesis.

- It signals catabolism and need for nutritional/clinical intervention.

- Monitor high-risk patients (trauma, burns, sepsis, prolonged immobility) for negative nitrogen balance.

When explaining the cause of frequent urinary tract infections related to immobility, the nurse understands that immobility may result in which of the following?

Explanation

Lack of movement can lead to incomplete bladder emptying and decreased frequency of voiding - called urinary stasis - which allows bacteria to multiply and increases the risk of UTIs. Immobility also contributes to other urinary problems (e.g., increased urinary calcium from bone breakdown).

Rationale for correct answer:

2. Urinary stasis: When a patient is immobile, they may not void frequently or completely (because of decreased mobility to toileting, decreased abdominal and pelvic muscle tone, or dependency), causing urine to remain in the bladder. Urinary stasis provides a medium for bacterial growth and is a major risk factor for urinary tract infections (UTIs).

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Improved renal blood supply to the kidneys: Immobility does not improve renal blood flow. If anything, prolonged bed rest can reduce overall circulation and predispose to complications; improved renal perfusion is not a consequence of immobility.

3. Decreased urinary calcium: Immobility typically increases bone resorption, releasing calcium into the bloodstream and urine (hypercalciuria). So urinary calcium usually rises, not decreases.

4. Acidic urine formation: Urinary pH can vary with diet, medications, and infection; immobility itself does not reliably cause acidic urine. It’s urinary stasis and bacterial overgrowth that more directly increase UTI risk.

Take home points

- Urinary stasis from immobility is the main reason immobile patients have higher UTI risk.

- Encourage frequent voiding, timed toileting, appropriate hydration, and use of mechanical aids (bedpans/commodes) or catheter protocols to reduce UTI risk in immobile patients.

Isotonic exercises such as walking are intended to achieve which of the following? Select all that apply.

Explanation

Isotonic activities involve concentric and eccentric muscle contractions with joint movement (walking, cycling, swimming). They improve muscle tone, endurance, circulation, and joint mobility; with appropriate intensity they also increase muscle strength and mass. Acute cardiovascular responses include increased heart rate and cardiac output, while chronic adaptations improve resting cardiovascular efficiency.

Rationale for correct answer:

1. Increase muscle tone and improve circulation: Isotonic exercises (muscle contraction with joint movement, e.g., walking) promote muscle conditioning and enhance venous return and overall circulation.

3. Increase muscle mass and strength: Repeated isotonic contractions against resistance or body weight can increase muscle strength and, depending on intensity, muscle mass. Walking primarily improves endurance and tone, but isotonic activities overall can enhance muscle strength.

5. Maintain joint range of motion: Because isotonic exercises involve movement through joint ranges, they help maintain or improve joint mobility and prevent stiffness.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

2. Increase blood pressure: Blood pressure rises during exercise acutely, but the intended therapeutic effect of regular isotonic exercise is to improve cardiovascular fitness and typically lower resting blood pressure over time. Increasing BP is not a desired long-term goal.

5. Decrease heart rate and cardiac output: During isotonic exercise heart rate and cardiac output increase to meet metabolic demands. Regular training can decrease resting heart rate and improve stroke volume (so exercise improves efficiency), but the immediate effect is an increase.

Take home points

- Isotonic exercises (like walking) improve muscle tone, circulation, endurance, and help maintain joint range of motion.

- Expect increased heart rate and cardiac output during activity, but regular isotonic exercise improves resting cardiovascular fitness and can lower resting blood pressure and heart rate over time.

A patient has been on bed rest for over 5 days. Which of these findings during the nurse’s assessment may indicate a complication of immobility?

Explanation

Prolonged bed rest can affect multiple systems—musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, respiratory, urinary, and gastrointestinal. Nurses must recognize early signs such as decreased peristalsis to prevent further complications through interventions like mobilization, hydration, and dietary management.

Rationale for correct answer:

1. Decreased peristalsis: Prolonged immobility slows gastrointestinal motility, leading to decreased peristalsis. This may cause constipation, fecal impaction, and discomfort—common complications of inactivity and reduced muscle tone in the abdomen. Encouraging fluids, fiber intake, and ambulation helps prevent this.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

2. Decreased heart rate: Although resting heart rate may slightly decrease with bed rest, it is not a typical complication of immobility. The more significant cardiovascular effects include orthostatic hypotension and venous stasis, not bradycardia.

3. Increased blood pressure: Immobility is more commonly associated with orthostatic hypotension due to blood pooling in the lower extremities and decreased cardiac workload, not hypertension.

4. Increased urinary output: Inactivity tends to decrease urinary output and promote urinary stasis, which increases the risk for urinary tract infection (UTI) and renal calculi. Increased output would not indicate a complication of immobility.

Take-home points

- Decreased peristalsis is a hallmark complication of prolonged immobility, often leading to constipation and discomfort.

- Regular mobility and repositioning are essential to maintain body system function and prevent complications during extended bed rest.

Practice Exercise 2

Mr. Brown is experiencing some difficulty breathing. The nurse most appropriately assists him into which position?

Explanation

Upright positions (Fowler’s) facilitate lung expansion by allowing the diaphragm to move more freely and reducing abdominal pressure on the chest, which improves oxygenation and comfort in dyspneic patients.

Rationale for correct answer:

3. Fowler’s position: Fowler’s (sitting upright at 45–90°) promotes maximal chest expansion and diaphragmatic descent, reduces abdominal pressure on the thorax, and improves ventilation and oxygenation. It’s the most appropriate immediate position for a patient experiencing difficulty breathing.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Dorsal recumbent position: Dorsal recumbent (supine with knees bent) lies the patient flat on their back. This position reduces diaphragmatic excursion and is not optimal for someone who is short of breath.

2. Lateral position: Side-lying (lateral) may be useful for airway protection, certain respiratory conditions, or to improve ventilation of a dependent lung in unilateral disease, but it is not the standard first choice for general dyspnea.

4. Sims’ position: Sims’ (semi-prone, used commonly for rectal procedures or enema administration) is not used to relieve dyspnea and may compromise respiratory mechanics.

Take home points

- Place dyspneic patients in Fowler’s position to improve ventilation and ease breathing.

- Positioning is a simple, immediate nursing intervention that can significantly improve respiratory status while further assessment and treatments proceed.

A bedridden patient who is blind is admitted to a healthcare facility from his or her home with pressure ulcers on the sacral area. Which nursing diagnosis would be a priority?

Explanation

Nursing priorities focus first on actual, immediate threats to health and safety - here, an existing skin breakdown that can rapidly worsen or become infected. Effective care simultaneously treats the acute problem and addresses underlying contributors (immobility, nutrition, incontinence, sensory deficits) to prevent recurrence.

Rationale for correct answer:

2. Impaired Skin Integrity related to immobility: The patient already has actual pressure ulcers on the sacrum. Impaired skin integrity directly addresses the existing wound problem and its cause (immobility). Actual problems that threaten tissue viability, infection risk, pain, and further deterioration take priority over potential/risk problems.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Risk for Imbalanced Body Temperature related to stage 2 pressure ulcer: A risk diagnosis describes a potential future problem. Although severe infections or large wounds can affect temperature regulation, a stage 2 sacral pressure ulcer in a single area is unlikely to cause an immediate body-temperature imbalance.

3. Feeding Self-Care Deficit related to blindness: Blindness may impair independent feeding, but it is not inherently as immediately threatening as an existing pressure ulcer that risks infection and further tissue loss. This is an important problem to assess and plan for assistive strategies, but not the highest priority given the current wounds.

4. Activity Intolerance related to prolonged bed rest: Activity intolerance is likely present and contributes to immobility, but it is more of a contributing/related condition. The immediate problem requiring nursing action on admission is the impaired skin integrity.

Take home points

- Actual problems that threaten tissue viability or life take priority over potential/risk diagnoses.

- Treat the wound promptly and address contributing factors (immobility, moisture, nutrition, sensory impairment) to prevent progression and complications.

Five minutes after the client’s first postoperative exercise, the client’s vital signs have not yet returned to baseline. Which is an appropriate nursing diagnosis?

Explanation

When a client shows measurable signs (e.g., abnormal vital signs, symptoms) after activity, choose an actual nursing diagnosis that reflects current physiologic intolerance. Reserve “risk for…” diagnoses for situations where hazards exist but no current manifestations are present.

Rationale for correct answer:

1. Activity Intolerance: This diagnosis is used when a client demonstrates actual inadequate physiological or psychological energy to endure or complete required or desired daily activities. The objective finding (vital signs not returning to baseline 5 minutes after activity) is evidence that the client is not tolerating the activity at this time.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

2. Risk for Activity Intolerance: “Risk for…” is used when no current evidence exists but risk factors are present. In this scenario there is current, measurable evidence (vital signs not back to baseline), so an actual diagnosis is appropriate rather than a risk diagnosis.

3. Impaired Physical Mobility: This focuses on limitation in independent physical movement (ambulation, range of motion). While the client may have limited tolerance, the key problem reported here is the inability to physiologically tolerate activity, not necessarily a limitation of movement itself.

4. Risk for Disuse Syndrome: This is a risk diagnosis referring to consequences of inactivity (muscle atrophy, bone demineralization, etc.). The client’s immediate problem is demonstrated intolerance to activity, not the future risk of disuse complications.

Take home points

- Use an actual nursing diagnosis (e.g., Activity Intolerance) when there is current, observable evidence of a problem.

- Choose a risk diagnosis only when risk factors exist but no current signs or symptoms are present.

When assessing a client’s gait, which does the nurse look for and encourage?

Explanation

Components of a normal gait pattern include: head posture and gaze, heel-to-toe foot contact, reciprocal arm swing, and trunk/pelvic rotation. Nurses observe gait to identify impairments - balance, coordination, strength, neurologic problems- and to teach or encourage safer, more efficient walking mechanics that reduce fall risk and conserve energy.

Rationale for correct answer:

1. The spine rotates, initiating locomotion: Normal gait includes coordinated rotation of the pelvis and trunk (spine) that contributes to stride length and balance. Trunk/pelvic rotation is part of normal locomotion and helps conserve energy and promote smooth, efficient movement - something the nurse observes and may encourage if limited.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

2. Gaze is slightly downward: A normal, safe gait is associated with the head up and gaze forward (looking ahead to navigate). A persistently downward gaze can impair balance and increase fall risk.

3. Toes strike the ground before the heel: Normal walking has a heel-strike (heel contacts first) followed by foot flat and toe-off. Toe-first contact is abnormal and suggests gait deviation.

4. Arm on the same side as the swing-through foot moves forward at the same time: Normal gait shows reciprocal arm swing: the arm opposite the swing leg moves forward (e.g., right leg forward - left arm forward). Same-side forward movement is abnormal and indicates poor coordination.

Take home points

- Normal gait - head up/gaze forward, heel-strike then toe-off, reciprocal arm swing (opposite arm to leg), and pelvic/trunk rotation for efficiency.

- Deviations from these patterns may signal mobility problems that need assessment or intervention.

The nurse is performing an assessment of an immobilized client. Which assessment causes the nurse to take action?

Explanation

Immobilized clients are at high risk for pressure injuries, pulmonary complications- atelectasis, deep-vein thrombosis, and urinary issues. Early skin changes are actionable findings requiring immediate preventive measures to avoid progression to ulceration.

Rationale for correct answer:

2. Reddened area on sacrum: New persistent redness over a pressure point (sacrum) suggests early pressure injury (stage I) from prolonged pressure. This requires immediate nursing action: relieve pressure- reposition, inspect skin closely, implement pressure-relief measures (turning schedule, specialty mattress), and document/monitor.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Heart rate 86 beats/min: A heart rate of 86 bpm is within normal adult range and does not alone indicate an urgent problem in an immobilized client.

3. Nonproductive cough: A nonproductive cough may be an early sign of atelectasis or developing pulmonary issue in an immobilized client and should be monitored and managed (incentive spirometry, deep-breathing exercises), but a reddened sacrum is more urgent for preventing tissue breakdown.

4. Urine output of 50 mL/h: Output of 50 mL/hour is above the commonly used minimum adequate threshold (≥30 mL/hour) and is acceptable. It does not by itself require immediate corrective action.

Take home points

- Early pressure-area redness is an urgent finding in an immobile client - reposition and institute pressure-relief measures immediately.

- Monitor respiratory and urinary status in immobilized patients, but prioritize skin breakdown prevention because pressure injuries can develop quickly and are largely preventable.

Practice Exercise 3

Why are mechanical aids necessary for patient handling and movement?

Explanation

Mechanical aids-such as hoists, slide sheets, and transfer boards-play a critical role in preventing workplace injuries among healthcare workers, especially back injuries, which are common with manual lifting. While proper body mechanics, teamwork, and physical fitness can contribute to safer handling, they are not sufficient by themselves. The introduction of mechanical aids aligns with occupational safety standards and promotes both staff well-being and patient comfort, ensuring safe and efficient transfers.

Rationale for correct answer:

2. Manual lifting techniques are not sufficient to protect nurses from injury: Research shows that manual lifting places excessive stress on the musculoskeletal system, particularly the back and shoulders. Even when using correct posture and teamwork, the physical demands can exceed safe limits.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Nurses do not have sufficient training using proper body mechanics to be safe: Nurses are taught proper body mechanics (e.g., wide base of support, bending knees, keeping load close). However, even with correct technique, manual lifting alone is not enough to prevent musculoskeletal injury, especially with heavier or immobile patients.

3. They reduce the time and number of staff needed to move the patient: Mechanical aids can indeed improve efficiency by reducing the number of staff required to transfer or reposition a patient. However, the primary rationale is staff safety and injury prevention.

4. Nurses are not as physically fit as they should be: Physical fitness does not guarantee protection from injury during lifting. Even a strong, fit nurse can suffer back injury when manually handling patients, since human lifting capacity is lower than many patient weights. Mechanical aids are necessary regardless of nurse fitness.

Take home points

- Manual lifting alone is unsafe-mechanical aids are essential to prevent musculoskeletal injuries in nurses.

- Mechanical aids not only protect staff but also improve efficiency and patient safety during handling and transfers.

While doing range-of-motion exercises with a patient who is bedridden, the nurse is aware of which of the following considerations?

Explanation

Safe principles of range-of-motion therapy: preserve joint mobility and prevent contractures by performing controlled movements within a patient’s comfortable range. ROM can be active (patient moves), active-assistive, or passive (nurse moves joint). Important principles are to support the joint, move smoothly, avoid forcing or jerking, stop at resistance (not pain), monitor for signs of intolerance (swelling, increased pain, increased respirations, pallor), and document what was done.

Rationale for correct answer:

4. Each joint is exercised to the point of resistance but not pain: Standard ROM technique is to move each joint until you feel firm resistance (end of available range) but never force beyond that point or into pain. This prevents overstretching, tissue damage, and discouragement from painful practice.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Neck hyperextension should be encouraged, particularly in older people: Neck hyperextension can be harmful (risking cervical strain, vertebral artery compromise, or discomfort) and is not routinely encouraged-especially in older adults with cervical spondylosis. Neutral alignment and gentle, controlled movement are preferred.

2. Exercises should be continued until the patient is fatigued: Exercises that cause fatigue increase risk of injury and discourage participation. ROM is intended to maintain mobility, prevent contractures, and preserve joint health; stop before marked fatigue and allow rest between sets.

3. Exercises should be done frequently to lessen pain for the patient: Regular movement can reduce stiffness and pain over time, but frequency must be balanced with rest and tolerance. The statement is overly broad and could be unsafe if it encourages doing too many repetitions or exercising into pain.

Take home points

- Never force ROM beyond the patient’s tolerance.

- Regular ROM prevents stiffness, but avoid causing fatigue or injury; always support the joint and watch for adverse signs.

When a patient is using a cane for maximal support, the nurse is aware that the patient should do which of the following?

Explanation

Proper cane use includes holding it in the hand opposite the weaker leg (strong side), using the cane to share weight and improve balance, keeping the elbow slightly flexed, and coordinating the sequence of cane and leg movements so that the cane provides support when the weaker limb bears weight. Correct technique reduces fall risk and promotes efficient, safer ambulation.

Rationale for correct answer:

2. Distribute weight evenly between the feet and the cane: When using a cane for maximal support, the user should place some of their body weight through the cane while walking so that the load is shared between the cane and the legs. This decreases the force that must be borne by the weaker limb and improves balance and safety.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Hold the cane on the weaker side: The cane should be held in the stronger (unaffected) hand - that is, on the side opposite the weaker leg. Holding it on the stronger side lets the cane provide support and off-load weight from the weaker limb. Holding it on the weak side reduces stability.

3. Keep the elbow that is holding the cane straight and stiff: The elbow should be slightly flexed (about 20–30°) for proper leverage and comfort. A locked, stiff elbow transmits forces awkwardly and increases risk of discomfort or injury.

4. Advance the weaker foot ahead of the cane: The safe technique is to move the cane forward (about one small step’s length) and then advance the weaker (affected) leg toward or to the level of the cane; the stronger leg then steps past. Advancing the weaker foot ahead of the cane increases instability and fall risk.

Take home points

- Hold the cane on the stronger side (opposite the weak leg) and use it to share weight - don’t hold it on the weak side.

- Keep the elbow slightly flexed and advance the cane first, then the weaker leg - coordinate movements for stability.

To increase stability during client transfer, the nurse increases the base of support by performing which action?

Explanation

Basic principles of body mechanics and safe patient handling include how the base of support, center of gravity, and leverage affect stability. For safe transfers, nurses should widen their base of support, lower their center of gravity (bend knees), keep the load close to the body, and use leg muscles rather than the back.

Rationale for correct answer:

2. Spacing the feet farther apart: Widening the stance increases the base of support (BOS). A larger BOS makes it easier to keep the center of gravity (COG) within the BOS during movement, which improves overall stability during transfers.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Leaning slightly backward: Leaning backward shifts the nurse’s center of gravity posteriorly and can actually reduce balance or place the nurse at risk of falling backward. It does not widen the base of support; it merely shifts weight and may make the transfer less stable.

3. Tensing the abdominal muscles: Tensing core muscles improves trunk stability and protects the back, which helps safe body mechanics, but it does not increase the base of support. It’s supportive, not a method of enlarging the BOS.

4. Bending the knees: Bending the knees lowers the center of gravity and uses leg muscles rather than the back (good body mechanics), which improves stability and reduces injury risk - however it does not increase the width of the base of support.

Take home points

- Widen your stance (feet farther apart) to increase the base of support and improve stability during transfers.

- Combine a wider base with bending the knees and keeping the patient close to your body to maximize safety and reduce back injury risk.

Comprehensive Questions

What term would the nurse use to identify the strong, flexible, inelastic fibrous bands and flattened sheets of connective tissue that attach muscle to bone?

Explanation

Tendons (including aponeuroses) connect muscle to bone and are built for high tensile strength so muscle force is efficiently transmitted to the skeleton; ligaments connect bones and stabilize joints; cartilage cushions and provides smooth surfaces and structural form; and joints are the anatomical sites of bone articulation. Clinically, recognizing these differences helps distinguish injury types (e.g., strain involves muscle/tendon, sprain involves ligament, cartilage damage leads to joint pain/degeneration).

Rationale for correct answer:

1. Tendons are dense, regularly arranged fibrous connective tissue made mostly of parallel collagen fibers (type I). They attach muscle to bone, transmit the force of muscle contraction to produce movement, and are strong and relatively inelastic. Flattened sheets of tendon tissue are called aponeuroses.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

2. Ligaments are also fibrous connective tissue but they connect bone to bone (or bone to cartilage) at joints. Their fiber arrangement and elastic content allow them to stabilize joints and limit excessive movement. They are functionally and anatomically distinct from tendons.

3. Cartilage is a firm but flexible avascular connective tissue (types: hyaline, elastic, fibrocartilage). It provides cushioning, smooth articular surfaces, and structural support (e.g., intervertebral discs, articular surfaces, ear). It does not attach muscle to bone.

4. Joints are the site where two or more bones meet. Joints are structures composed of bone ends plus associated cartilage, ligaments, synovial membranes (in synovial joints), etc.—they are not connective-tissue bands that attach muscle to bone.

Take home points:

- Tendons attach muscle to bone (strong, mostly inelastic collagen bundles; aponeuroses are flattened tendons).

- Ligaments attach bone to bone (stabilize joints).

The nurse is assisting a patient with conditioning exercises to prepare for ambulation. The nurse correctly instructs the patient to do what?

Explanation

Conditioning prepares muscles for weight-bearing and improves confidence with transfers and walking. Interventions should be individualized, start gently, avoid Valsalva, monitor vital signs and symptoms, and progressively increase intensity and duration as tolerated.

Rationale for correct answer:

2. Breathe in and out smoothly during quadriceps drills: Proper breathing during conditioning and quad sets improves oxygenation, prevents undue intrathoracic/intra-abdominal pressure, and lowers cardiovascular strain. Quadriceps drills are commonly used to build strength for standing and ambulation, and breathing smoothly is essential.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Do full-body pushups in bed six to eight times daily: Bed push-ups can strengthen upper body muscles used for transfers, but prescribing “full-body pushups six to eight times daily” as a blanket instruction is unrealistic and may cause fatigue or be unsafe for some patients. Exercise prescription must be individualized.

3. Dangle on the side of the bed for 30 to 60 minutes: “Dangling” (sitting on the side of the bed) is used to assess tolerance and help orthostatic adaptation, but starting with 30–60 minutes is excessive and may precipitate orthostatic hypotension, dizziness, or nausea. Begin with short intervals, then gradually increase.

4. Allow the nurse to bathe the patient completely to prevent fatigue: While conserving energy is appropriate at times, encouraging independence and graded activity (having the patient perform as much as safely possible) helps conditioning. Full assistance for all ADLs impedes strengthening needed for ambulation.

Take home points

- Breathe smoothly during strengthening exercises to avoid Valsalva and undue cardiopulmonary strain.

- Progress activity gradually and promote patient participation rather than excessive passive care that prevents conditioning.

In many situations, a patient has sufficient strength to walk if he or she can do which of the following?

Explanation

Functional assessment of mobility - specifically which simple bedside observation best predicts whether a patient has the strength and endurance to walk. Walking requires coordinated lower-extremity strength, trunk stability, balance and some cardiovascular endurance; a patient who can sit unsupported for a prolonged period demonstrates many of these capabilities and is more likely to tolerate standing and ambulation than someone who can only perform minimal isolated movements.

Rationale for correct answer:

3. Raise the foot off the bed 1 inch: Being able to lift the foot slightly against gravity indicates sufficient quadriceps and hip flexor strength, which are critical muscle groups for initiating steps and supporting body weight during walking. This simple bedside test directly assesses lower-limb strength needed for ambulation.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Lie prone for 1 hour: Tolerating a prone position only shows postural tolerance, not active lower-limb strength or coordination needed for ambulation.

2. Bathe him- or herself: Self-bathing demonstrates independence in activities of daily living (ADLs) but may be performed sitting down. It doesn’t reliably test lower-extremity strength for ambulation.

4. Sit up in bed for 1 hour: Sitting up tests trunk stability and endurance, but it does not directly confirm that the leg muscles are strong enough to support walking.

Take home points

- Raising the foot off the bed = direct sign of lower-limb strength needed for ambulation.

- Other activities (sitting up, bathing, lying prone) show endurance or independence but do not confirm walking strength.

Mrs. Eden tells the nurse she feels faint while walking in the corridor with the nurse. What should the nurse do?

Explanation

For a patient experiencing presyncope or syncope while ambulating, the nurse’s priority is fall prevention and restoring cerebral perfusion - achieved by stopping ambulation, supporting the patient, and getting them into a seated or supine position quickly and gently. After stabilizing, the nurse should assess vitals, check for symptoms (chest pain, diaphoresis, paleness), review medications, and arrange further evaluation as indicated.

Rationale for correct answer:

4. Guide her to a nearby chair, easing her onto it to rest: Helping the patient to sit immediately lowers the center of gravity, reduces orthostatic strain, and prevents a fall. Once seated or supine, the nurse should assess airway/breathing/circulation, loosen tight clothing, measure vital signs, and be prepared to place the patient supine with legs elevated if symptoms worsen.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Instruct the patient to quicken her pace so they can return to her room: Speeding up increases metabolic and cardiovascular demand and raises the risk of collapse or falling. Do not accelerate a patient who feels faint.

2. Leave her momentarily to find another nurse to help: Leaving a patient who is feeling faint removes immediate support and increases risk of injury if she collapses. The nurse should stay with and support the patient.

3. Advise her to look down at her feet to help maintain her balance: Looking down is not a reliable safety maneuver for syncope and may actually worsen dizziness or compromise balance. The priority is to reduce orthostatic stress and get the patient into a safe sitting/lying position.

Take home points

- If a patient feels faint while walking, stop immediately and assist the patient to sit or lie down - do not leave them or make them walk faster.

- Preventing a fall is the first priority; after the patient is safe, assess vital signs and consider causes such as orthostatic hypotension, medications, hypovolemia, or cardiac issues.

The use of patient care ergonomics is associated with which of the following patient outcomes?

Explanation

Ergonomic practices (use of lifts, transfer devices, proper body mechanics, and team approaches) are implemented to protect caregivers from injury and to improve patient safety and comfort during movement. When used correctly, ergonomics promote safer transfers, preserve patient skin integrity, maintain dignity, and often facilitate earlier mobilization and rehabilitation.

Rationale for correct answer:

1. Increased patient comfort, security, and dignity during lifts and transfers: Patient-centered ergonomics are designed to protect both patients and caregivers. Proper ergonomics reduce painful manual handling, minimize jarring or sliding, and support safe, dignified transfers - improving comfort, security, and dignity.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

2. Increased patient falls, skin tears, and abrasions: The opposite is true: when ergonomics are applied correctly, the incidence of falls, skin tears, and abrasions generally decreases because movements are controlled, and friction/shear are minimized.

3. Decreased patient movement and independence: Ergonomic interventions are intended to enable safer mobility and independence where possible. While some mechanical aids require staff assistance initially, the goal is to preserve or restore safe movement, not reduce it.

4. Increased friction and shearing: Good ergonomics aim to reduce friction and shear (for example, by using slide sheets, repositioning aids, or lifts), thereby lowering risk of skin breakdown.

Take home points

- Patient-care ergonomics improve safety and dignity - they make lifts/transfers more comfortable and secure for patients.

- Proper ergonomics reduce risks (falls, skin injury) and support safer mobility; they are implemented to protect both patients and staff.

Which of the following should the nurse do when assisting the patient to ambulate?

Explanation

Safe ambulation principles: assessing readiness, using proper assistive devices and techniques (gait belt use, side/behind positioning), preventing fatigue, and promoting independence while minimizing fall risk. The gait belt is a simple, effective tool that gives the nurse control and reduces the need to use awkward lifting postures. Safe ambulation also requires good footwear, clear environment, appropriate pacing, and monitoring for signs of intolerance.

Rationale for correct answer:

3. Use a gait belt to provide support: A properly applied gait belt gives the nurse secure, ergonomic handholds to assist, steady, and catch the patient if they stumble. It reduces fall risk and protects both patient and caregiver when used correctly.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Place a hand under the axilla to provide support: Placing a hand under the axilla can be uncomfortable or painful for the patient and risks injury to the caregiver (or the patient’s brachial plexus). It also gives poor leverage and less control than using a gait belt or holding the patient at the trunk/hips.

2. Ensure the patient walks as far as possible for as long as possible: Pushing a patient to walk farther/longer than tolerated increases the risk of fatigue, dizziness, falls, and cardiac or respiratory compromise. Ambulation should be progressed gradually and individualized to the patient’s endurance and safety.

4. Encourage the patient to watch their feet to ensure a steady gait: Looking down limits visual input about the environment, can throw off balance, and often worsens gait stability. Patients should be encouraged to look forward, scan the path, and use assistive devices correctly.

Take home points

- Use a gait belt for support - it provides the safest, most controlled way to steady and assist a patient during ambulation.

- Progress ambulation gradually and keep the patient looking forward - avoid overexertion and discourage looking down at the feet which can destabilize gait.

When working with an older patient to develop an exercise program, the nurse would recommend which of the following?

Explanation

Key principles of safe exercise prescription for older adults include individualizing frequency/intensity, using the talk test to gauge exertion, correctly calculating target heart rates if used, and obtaining medical clearance when indicated. A comprehensive program for older adults should incorporate aerobic activity, strength training, balance, and flexibility, start gradually, and progress as tolerated under clinical guidance.

Rationale for correct answer:

4. Obtaining medical clearance before beginning the program: Older adults - particularly those with chronic conditions, sedentary lifestyle, or multiple risk factors - should have medical clearance or assessment before starting a new exercise program. This reduces the risk of adverse cardiac or musculoskeletal events and helps tailor the safe intensity and types of activity.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. A frequency of six times a week: Exercise programs should be individualized, include rest days, and consider current fitness, comorbidities, and tolerance. General recommendations are usually expressed as minutes per week (e.g., 150 min moderate activity) with strength and balance sessions included.

2. Exercising to the point of breathlessness when trying to speak: The “talk test” is used clinically: during moderate-intensity activity a person should be able to talk but not sing. If someone becomes breathless to the point they cannot speak, intensity is too high and should be reduced.

3. Maintaining a target heart rate of 220 plus age: The common maximal heart-rate estimate is 220 − age (not plus age), and target exercise HR is a percentage of that maximum. Heart-rate targets should be individualized and determined after appropriate assessment.

Take-home points

- Get medical clearance when appropriate - especially for older or sedentary patients or those with chronic conditions.

- Use the talk test and start low-go slow - avoid working to the point where the patient cannot speak;

A client weighs 250 pounds and needs to be transferred from the bed to a chair. Which instruction by the nurse to the unlicensed assistive personnel (UAP) is most appropriate?

Explanation

For heavy or non-assisting clients, nurses should prioritize mechanical lifts and team transfers rather than manual lifting, and UAPs should be given clear instructions that follow facility policy and evidence-based safe-handling practices.

Rationale for correct answer:

3. “Use the mechanical lift and another person to transfer the client from the bed to the chair.” This gives a clear, evidence-based instruction: use a mechanical lift (or other safe patient-handling device) plus an assistant as needed. Mechanical lifts reduce injury risk to staff and are the recommended method for transferring patients above manual-lift weight thresholds or when the patient cannot assist.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. “Using proper body mechanics will prevent you from injuring yourself.” Teaching proper body mechanics is important, but this statement overpromises: even when using correct technique, manually lifting very heavy patients still places staff at high risk of injury.

2. “You are physically fit and at lesser risk for injury when transferring the client.” This assumes the UAP’s fitness protects them-an unsafe assumption. Staff fitness does not eliminate the risk of musculoskeletal injury from manual transfers of heavy clients and is not an acceptable reason to forgo mechanical aids or additional help.

4. “Use the back belt to avoid hurting your back.” Back belts have not been shown to reliably prevent injury and are not a substitute for safe patient-handling equipment and team assistance. Relying on a back belt may give false security and is not the safest instruction.

Take home points

- For heavy or non-assisting patients, use mechanical lifts and assistance-don’t rely on manual lifts even if staff feel “fit.”

- Clear, safety-focused instructions to UAPs protect both staff and patients; belts or promises of “proper mechanics” alone are insufficient.

A nurse is teaching a client about active range-of-motion (ROM) exercises. The nurse then watches the client demonstrate these principles. The nurse would evaluate that teaching was successful when the client does which of the following?

Explanation

Principles of teaching and performing active ROM: safety (do not force movement or go past resistance), adequacy (multiple repetitions and appropriate frequency), and consistency (use a regular sequence so exercises are complete and measurable). The nurse should teach pain-free movement through the available range, an appropriate number of repetitions and sessions per day, and a consistent order so the client performs a complete, safe program.

Rationale for correct answer:

4. Uses the same sequence during each exercise session: Using a consistent sequence helps ensure all joints/muscle groups are exercised, reinforces correct technique, and reduces the chance of forgetting or skipping movements. Consistency also helps the nurse evaluate progress and identify problems.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Exercises past the point of resistance: Pushing past resistance risks injury, pain, and joint damage. Active ROM should be performed only through the available, pain-free range; resistance indicates the limit of safe motion.

2. Performs each exercise one time: One repetition is insufficient to maintain or improve mobility. ROM programs normally call for multiple repetitions (often several sets of 8–10, or as prescribed) to be effective.

3. Performs each series of exercises once a day: Once-daily may be inadequate for many clients; ROM exercises are commonly done multiple times per day depending on the condition and goals. The point being tested is correct technique and consistency, not minimal frequency.

Take home points

- Never push a joint past its point of resistance or into pain - active ROM must be pain-limited.

- Consistency matters: perform a complete, repeated program in a consistent sequence so progress and problems are easy to monitor.

Performance of activities of daily living (ADLs) and active range of-motion (ROM) exercises can be accomplished simultaneously as illustrated by which of the following? Select all that apply

Explanation

Functional ROM- how routine ADLs and mobility tasks can simultaneously serve as therapeutic active range-of-motion exercises. Therapists and nurses often incorporate ROM training into meaningful activities (like eating, grooming, ambulation) so patients practice needed motions in context, improving adherence and functional gains.

Rationale for correct answer:

1. Elbow flexion with eating and bathing: Both eating (bringing a utensil to the mouth) and many bathing tasks (washing face, hair, underarms) use repeated elbow flexion. Encouraging ADLs provides functional repetitions of elbow flexion as active ROM.

4. Thumb ROM with eating and writing: Eating (grasping utensils) and writing (holding a pen/pencil) require thumb opposition and fine thumb movement-excellent opportunities for active ROM of the thumb.

5. Hip flexion with walking: Walking involves repeated hip flexion during the swing phase. Ambulation is a primary functional activity that provides active ROM for the hip.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

2. Elbow extension with shaving and eating: Shaving and eating primarily involve elbow flexion (bringing hand to face/mouth), not elbow extension. Elbow extension is used to reach away from the body, which is not the main movement in these ADLs.

3. Wrist hyperextension with writing: Writing uses a functional amount of wrist extension (and fine finger movement), but hyperextension (excessive extension beyond normal ROM) is neither necessary nor desirable and could cause strain. The activity provides normal wrist ROM, not hyperextension.

Take home points

- Use everyday activities (self-care and mobility) as opportunities for active ROM-this makes exercise purposeful and more likely to be repeated.

- Match the joint/movement needed in the ADL to the ROM goal.

The client is ambulating for the first time after surgery. The client tells the nurse, “I feel faint.” Which is the best action by the nurse?

Explanation

The immediate priority actions for a patient reporting presyncope/dizziness during ambulation - fall prevention and rapid safe positioning. The nurse’s first responsibility is to protect the client from falling (assist to a chair or floor), then assess (vital signs, skin color, bleeding), provide interventions (oxygen, fluids, medication review) and call for help if needed.

Rationale for correct answer:

4. Assist the client to a nearby chair: The priority is immediate safety: support the client and help her sit (or, if no chair is available, help her to the floor while protecting her head). This prevents a fall, allows measurement of vital signs, and lets you assess for orthostatic hypotension, blood loss, pain, medication effects, or other causes.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

1. Find another nurse for help: Getting help may be appropriate after the client is safe, but the immediate priority is preventing a fall or injury. Searching for help first delays immediate protection of the client.

2. Return the client to her room as quickly as possible: Rapid movement (walking the client back) risks the client fainting and falling. Move her safely and steadily to the nearest stable surface rather than hurriedly trying to get to the room.

3. Tell the client to take rapid, shallow breaths: Rapid, shallow breathing is not helpful and may increase dizziness. If anxiety or hyperventilation were present, breathing techniques would be considered, but the immediate action for faintness is to get the client safely to a chair or to the floor.

Take home points

- Immediately support and seat a patient who feels faint to prevent falls; don’t delay looking for help.

- After the client is safe, assess vital signs and possible causes (orthostatic hypotension, blood loss, medication effects) before further movement.

Before transferring a patient from the bed to a stretcher, which assessment data does the nurse need to gather? Select all that apply

Explanation

The nurse must perform a pre-transfer risk assessment (weight, mobility, activity tolerance) and follow a safe-mobility algorithm or facility policy to choose the correct equipment and number of staff. The goal is to protect both patient and caregivers by preventing falls and musculoskeletal injury.

Rationale for correct answer:

1. Patient’s weight: Knowing the patient’s weight is essential to decide whether manual transfer is safe or whether a mechanical lift or additional staff are required (many safe-handling algorithms and lift manufacturers set weight limits). Weight helps determine the number of caregivers and the type of equipment (full-body sling, sit-to-stand lift, etc.).

2. Patient’s activity tolerance: Activity tolerance (how long/what intensity the patient can tolerate without significant symptoms) indicates whether the patient can assist or needs rest breaks, and helps predict cardiopulmonary responses during transfer. This affects how you plan and pace the transfer and whether extra monitoring is needed.

3. Patient’s level of mobility: Assessing mobility (ability to bear weight, to pivot, to follow commands, to assist) directly determines whether a one-person transfer is safe, or if two people or a mechanical device must be used. Mobility screening tools and bedside mobility assessments are standard before any transfer.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

4. Recent laboratory values: Labs can be relevant in special situations (e.g., severe anemia, coagulopathy, electrolyte abnormalities causing weakness or orthostatic symptoms), but they are not a standard part of the transfer safety checklist unless there is a specific clinical reason to suspect a lab-related risk. Assess functional status first and request labs selectively.

5. Nutritional intake: Nutritional intake is important for overall care planning (wound healing, long-term recovery), but it generally does not determine the immediate safety of a bed-to-stretcher transfer. It would not normally change the equipment or number of staff required for the transfer.

6. Safe mobility algorithm: Using a facility or evidence-based safe mobility algorithm (or mobility assessment tool) integrates weight, mobility, ability to assist, and other risk factors and guides the nurse to the correct device, number of caregivers, or whether a lift is required. Algorithms reduce guesswork and staff injuries.

Take home points

- Always assess weight, mobility level, and activity tolerance before a transfer.

- These facts determine whether mechanical lifts or extra staff are needed.

A 51-year-old adult comes to a medical clinic for an annual physical exam. The patient is found to be slightly overweight and reports being inactive, walking only 2 to 3 times a week with his wife after work. He has good muscle strength and coordination of lower extremities. Which of the following recommendations from the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans should the nurse suggest? Select all that apply

Explanation

The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans provide evidence-based recommendations to promote health, prevent chronic disease, and improve quality of life through regular physical activity. Nurses play a vital role in educating and motivating clients to incorporate aerobic and muscle-strengthening activities safely and effectively into their daily lives.

Rationale for correct answers:

1. Move more and sit less throughout the day: According to the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, adults should reduce sedentary behavior by moving more throughout the day. Any amount of movement is beneficial compared to sitting still, especially for individuals with sedentary lifestyles.

3. Perform muscle-strengthening activities using light weights on 2 or more days a week: The guidelines recommend that adults perform muscle-strengthening activities of moderate or greater intensity on 2 or more days per week, targeting all major muscle groups. Using light weights with proper resistance is appropriate for beginners.

4. Walk at a vigorous pace with wife at least 150 minutes over five days a week: Adults should perform at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity (e.g., brisk walking) or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity weekly. Spreading the activity over five days promotes consistency and improves cardiovascular health, weight management, and endurance.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

2. Participate in at least 90 minutes a week of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity:

This amount is below the recommended minimum. Adults should engage in at least 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic activity (such as brisk walking). Ninety minutes weekly is insufficient to achieve meaningful health benefits or meet guideline recommendations.

5. Focus on balance training: Balance training is mainly recommended for older adults (≥65 years) or those at risk of falls. This patient is 51 years old, has good coordination and muscle strength, and does not currently need specific balance training interventions.

Take-home points

- Adults should perform at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity per week plus muscle-strengthening exercises on 2 or more days weekly.

- Encouraging clients to move more and sit less throughout the day can greatly enhance overall health, especially for those with sedentary lifestyles.

Family members have asked for a meeting with the nursing staff of an assisted living residential center to discuss the feasibility of their mother using a walker. The family is worried that her health is declining; they wonder whether she can use the walker safely. Which of the following instructions should the nurse give the family after assessing that it is safe for the woman to use a walker? Select all that apply

Explanation

Nurses must assess each client’s strength, balance, and coordination before recommending an appropriate assistive device. Proper education on walker use promotes independence, safety, and confidence during ambulation while minimizing the risk of injury.

Rationale for correct answers:

1. A walker is useful for patients who have impaired balance: Walkers provide a broad base of support, helping individuals with impaired balance or weakness to maintain stability while ambulating. They are particularly useful for older adults or clients recovering from illness or surgery, as they reduce the risk of falls and promote safe mobility.

4. Walkers should not be used on stairs: Walkers are not designed for use on stairs due to stability and balance limitations. Attempting to use one on stairs poses a serious fall hazard. For clients who must use stairs, other assistive devices like handrails or canes should be used instead.

5. If the patient has difficulty advancing the walker, a walker with wheels is an option: For clients who have difficulty lifting a standard walker, a wheeled walker (rolling walker) is safer and easier to maneuver. It allows smoother movement and reduces upper-body strain, especially for clients with limited arm strength.

Rationale for incorrect answers:

2. The patient uses a walker by pushing the device forward: Walkers should not be pushed forward forcefully. Instead, the patient should lift and place the walker about one step ahead (unless it has wheels). Pushing a standard walker may cause it to tip or roll uncontrollably, increasing the risk of falls.

3. Leaning over the walker improves the patient’s balance: Leaning over the walker is unsafe and promotes poor posture. It shifts the center of gravity forward, increasing fall risk and leading to back strain. The correct position is to stand upright inside the walker, keeping the elbows slightly flexed and the body aligned.

Take-home points

- Walkers enhance stability for clients with impaired balance but should never be used on stairs or leaned on excessively.

- Education on proper technique and device selection (standard vs. wheeled walker) is crucial for promoting safety and maintaining functional mobility in older adults.

A patient has an order for application of compression stockings. Place the following steps for application of the compression stockings in the correct order:

Explanation

Compression stocking application,is an important nursing intervention used to prevent venous thromboembolism (VTE) and reduce venous stasis in immobile patients. Proper sizing, correct technique, and smooth application are essential to maintain circulation and prevent complications such as skin breakdown or constriction.

Rationale for correct answers:

Step 1-- 2. Use tape measure to measure patient’s leg for proper stocking size.

Accurate measurement ensures the stockings fit correctly. Ill-fitting stockings can cause impaired circulation or fail to provide adequate compression.

Step 2-- 4. Turn elastic stocking inside out, keeping hand inside holding heel. Take other hand and pull stocking inside out until reaching the heel.

This step prepares the stocking for easier and smoother application, ensuring the heel and toe portions are properly aligned.

Step 3—1. Place patient’s toes into foot of stocking up to the heel; keep smooth.

Starting at the toes ensures proper fit and alignment. The fabric should remain smooth to prevent skin irritation or pressure injury.

Step 4—5. Slide remaining portion of stocking over patient’s foot, covering toes. Be sure foot fits into toe and heel of stocking.

This step ensures the stocking conforms to the foot’s shape and provides even pressure distribution.

Step 5-- 3: Slide stocking up over patient’s calf until sock is completely extended.

Pulling the stocking smoothly up the leg completes the process and ensures proper compression without folds or wrinkles that may impede circulation.

Take-home points

- Compression stockings prevent venous stasis and thrombus formation in clients with limited mobility or at risk for DVT.

- Proper sizing and smooth application technique are vital to ensure therapeutic effectiveness and prevent circulatory impairment.

Exams on Mobility

Custom Exams

Login to Create a Quiz

Click here to loginLessons

Naxlex

Just Now

Naxlex

Just Now

Notes Highlighting is available once you sign in. Login Here.

Objectives

- Identify Variables that influence body alignment and mobility.

- Differentiate isotonic, isometric, and isokinetic exercise.

- Describe the effects of exercise and immobility on major body systems.

- Assess body alignment, mobility, and activity tolerance, using appropriate interview and physical assessment skills.

- Develop nursing diagnoses that correctly identify mobility problems amenable to nursing interventions.

- Utilize principles of body mechanics when appropriate.

- Use safe patient handling and movement techniques and equipment when positioning, moving, lifting, and ambulating patients.

- Plan, implement, and evaluate nursing care related to select nursing diagnoses involving mobility problems.

Introduction

A strong, well-developed body of research evidence supports the role of exercise in improving the health status of individuals with cardiovascular disease, pulmonary dysfunction, disabilities of aging, and depression.

A growing body of research supports the preventive and therapeutic effects of exercise for individuals with hypertension, osteoporosis, coronary heart disease, mental health disorders, diabetes, cancer, arthritis, chronic fatigue syndrome.

An activity-exercise pattern refers to a person’s routine of exercise, activity, leisure, and recreation. It includes:

- activities of daily living (ADLs) that require energy expenditure such as hygiene, dressing, cooking, shopping, eating, working, and home maintenance.

- the type, quality, and quantity of exercise, including sports.

Mobility, the ability to move freely, easily, rhythmically, and purposefully in the environment, is an essential part of living. People must move to protect themselves from trauma and to meet their basic needs

Movement

3.1 NORMAL MOVEMENT

Normal movement and stability are the result of an intact musculoskeletal system, an intact nervous system, and intact inner ear structures responsible for equilibrium.

It involves four basic elements: body alignment (posture), joint mobility, balance, and coordinated movement.

- Alignment and Posture

Proper body alignment and posture bring body parts into position in a manner that promotes optimal balance and maximal body function whether the client is standing, sitting, or lying down.

A person maintains balance as long as the line of gravity (an imaginary vertical line drawn through the body’s center of gravity) passes through the center of gravity (the point at which all of the body’s mass is centered) and the base of support (the foundation on which the body rests).

Abdominal and skeletal muscles function almost continuously, making tiny adjustments that enable an erect or seated posture despite the endless downward pull of gravity. The extensor muscles, often referred to as the antigravity muscles, carry the major load as they keep the body upright.

- Joint mobility:

The bones of the skeleton articulate at the joints, and most of the skeletal muscles attach to the two bones at the joint.

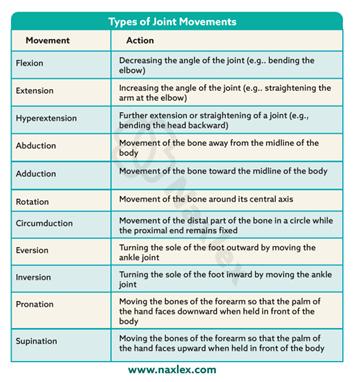

These muscles are categorized according to the type of joint movement they produce on contraction. Muscles are therefore called flexors, extensors, internal rotators, and the like.

The flexor muscles are stronger than the extensor muscles. Thus, when a person is inactive, the joints are pulled into a flexed (bent) position. If this tendency is not counteracted with exercise and position changes, the muscles permanently shorten, and the joint becomes fixed in a flexed position (contracture).

The range of motion (ROM) of a joint is the maximum movement that is possible for that joint. Joint range of motion varies from individual to individual and is determined by genetic makeup, developmental patterns, the presence or absence of disease, and the amount of physical activity in which the person normally engages.

- Balance:

The mechanisms involved in maintaining balance and posture are complex and involve informational inputs from the labyrinth (inner ear), from vision (vestibulo-ocular input), and from stretch receptors of muscles and tendons (vestibulospinal input).

Mechanisms of equilibrium (sense of balance) respond, frequently without our awareness, to various head movements.

Proprioception is the term used to describe awareness of posture, movement, and changes in equilibrium and the knowledge of position, weight, and resistance of objects in relation to the body.

- Coordinated movement:

Balanced, smooth, purposeful movement is the result of proper functioning of the cerebral cortex, cerebellum, and basal ganglia.

The cerebral cortex initiates voluntary motor activity, the cerebellum coordinates the motor activities of movement, and the basal ganglia maintain posture.

Factors Affecting Body Alignment and Activity

Body alignment, mobility, and daily activity are influenced by multiple factors: growth and development, nutrition, personal values/attitudes, external factors, and prescribed limitations.

1. Growth and Development

- Infants/Children: Movements initially reflexive - progress to controlled motor skills. Gross motor skills develop head-to-toe (head control - crawling - walking). Fine motor refinement (drawing, dressing, brushing teeth) occurs by preschool age. Immobility in children delays social/motor development.

- School-age (6–12 yrs): Motor skills refine further; PE and sports shape lifelong exercise patterns. Posture usually excellent.

- Adolescents: Growth spurts may cause postural issues (e.g., heavy bags, screen use). Habits may persist into adulthood.

- Adults (20–40 yrs): Few mobility issues except pregnancy, which alters balance. Moderate exercise is encouraged during pregnancy (with medical clearance). Benefits: prevents gestational diabetes, controls weight, reduces long-term obesity risk.

- Older Adults: Age-related changes: decreased muscle tone, bone density, flexibility, reaction time. Osteoporosis (common in women) - brittle bones, fractures, stooped posture, shuffling gait. Regular activity maintains strength, flexibility, bone health, reduces falls, obesity, diabetes, and improves mood.

2. Nutrition

Undernutrition: Weakness, fatigue, poor muscle development. Deficiencies: Vitamin D - bone deformities and Calcium & Vitamin D - osteoporosis risk.

Overnutrition (obesity): Alters posture, stresses joints, affects balance and movement.

3. Personal Values and Attitudes

Family influence shapes exercise habits. Sedentary lifestyle often passed on to children. Appearance, cultural roles, and location influence activity choices. Motivation can be enhanced through:

-

- Fun/social activities, music, goal-setting, progress tracking.

- Framing exercise as recreation, well-being, or self-care.

FIT model (Frequency, Intensity, Time) used for exercise prescription. Nurses should tailor exercise plans to client’s health, fitness, motivation, and safety.

4. External Factors

- Environment: Extreme heat/humidity - discourage activity. Safe, pleasant environments - encourage activity.

- Hydration: Short activity - 1–2 cups of water. Endurance events - hydration before, during, and after (water + sports drinks with sodium).

- Resources: Lack of money, facilities, or safe neighborhoods limits opportunities for activity.

- Technology: TV, computers, video games increase sedentary behavior (esp. in adolescents).

5. Prescribed Limitations

- Medical restrictions: Casts, splints, braces, traction limit movement to promote healing. Dyspnea - avoid exertion. Bed rest used for edema, pain relief, tissue repair, reducing oxygen needs.

- Types of bed rest vary: Strict confinement vs. bathroom privileges.

3.2 EXERCISE

People participate in exercise programs to decrease risk factors for chronic diseases and to increase their health and well-being.

Functional strength is another goal of exercise, and is defined as the ability of the body to perform work.

Activity tolerance is the type and amount of exercise or ADLs an individual is able to perform without experiencing adverse effects.

Types of exercise:

Exercise involves the active contraction and relaxation of muscles. Exercises can be classified according to the type of muscle contraction (isotonic, isometric, or isokinetic) and according to the source of energy (aerobic or anaerobic).

According to the type of muscle contraction:

- Isotonic (dynamic) exercises are those in which the muscle shortens to produce muscle contraction and active movement. Most physical conditioning exercises—running, walking, swimming, cycling.

Isotonic exercises increase muscle tone, mass, and strength and maintain joint flexibility and circulation. During isotonic exercise, both heart rate and cardiac output quicken to increase blood flow to all parts of the body.

- Isometric (static or setting) exercises are those in which muscle contraction occurs without moving the joint (muscle length does not change).

These exercises involve exerting pressure against a solid object and are useful for strengthening abdominal, gluteal, and quadriceps muscles used in ambulation; for maintaining strength in immobilized muscles in casts or traction; and for endurance training.

- Isokinetic (resistive) exercises involve muscle contraction or tension against resistance. During isokinetic exercises, the person tenses (isometric) against resistance. These exercises are used in physical conditioning and are often done to build up certain muscle groups.

According to the source of energy

- Aerobic exercise is activity during which the amount of oxygen taken into the body is greater than that used to perform the activity. Aerobic exercises use large muscle groups that move repetitively. Aerobic exercises improve cardiovascular conditioning and physical fitness.

- Anaerobic exercise involves activity in which the muscles cannot draw out enough oxygen from the bloodstream, and anaerobic pathways are used to provide additional energy for a short time. This type of exercise is used in endurance training for athletes such as weight lifting and sprinting.

Intensity of exercise can be measured in three ways:

1. Target heart rate. The goal is to work up to and sustain a target heart rate during exercise, based on the person’s age. To determine target heart rate, first calculate the person’s maximum heart rate by subtracting his or her current age in years from 220. Then obtain the target heart rate by taking 60% to 85% of the maximum. Because heart rates vary among individuals, the tests that follow are replacing this measure.

2. Talk test. This test is easier to implement and keeps most people at 60% of maximum heart rate or more. When exercising, the person should experience labored breathing, yet still be able to carry on a conversation.

3. Borg scale of perceived exertion: This scale measures “how difficult” the exercise feels to the person in terms of heart and lung exertion. The scale progresses from 1 to 20 with the following markers: 7 = very, very light; 9 = very light; 11 = fairly light; 13 = somewhat hard; 15 = hard; 17 = very hard; and 19 = very, very hard.

Nursing insights: Guidelines and Minimal Requirements for Physical Activity

FREQUENCY AND DURATION

- Aerobic: Cumulative 30 minutes or more daily (can be divided throughout the day) of “moderate intensity” movement as measured by talk test and perceived exertion scale.

- Stretching: Should be added onto that minimum requirement so that all parts of the body are stretched each day.

- Strength training: Should be added onto these minimum requirements so that all muscle groups are addressed at least three times a week, with a day of rest after training.

TYPE OF EXERCISE

- Aerobic: Elliptical exercisers, walking, biking, gardening, dancing, and swimming are recommended for all individuals including beginners and older adults. Activities that are more strenuous include jogging, running, Spinning, power yoga, bouncing, boxing, and jumping rope.

- Stretching: Yoga, Pilates, qigong, and many other flexibility programs are effective.

- Strength training: Resistance can be provided with weights, bands, balls, apparatus, and body weight.

SAFETY

- Stress the importance of balance and prevention of falls, proper clothing to ensure thermal safety, checking equipment for proper function, wearing a helmet and other protective gear, using reflective devices at night, and carrying identification and emergency information.

Benefits of Exercise

Regular exercise is essential for mental and physical health, supporting multiple body systems.

1. Musculoskeletal System

- Maintains/increases muscle size, tone, strength (hypertrophy with strenuous exercise).

- Improves efficiency of muscle contraction.

- Joints: exercise provides nourishment, increased flexibility, stability, ROM.

- Bones: weight-bearing exercise strengthens bones; prevents osteoporosis.

- Reduces weakness, frailty, depression, falls in older adults.

2. Cardiovascular System

- AHA: 150 min/week moderate OR 75 min/week vigorous exercise.

- Benefits:

- increased HR and contraction strength.

- increased cardiac output and circulation.

- Stress reduction.

- Aerobic exercises (walking, cycling, yoga) improve BP, HR variability, circulation, and lower stress.

3. Respiratory System

- Improves ventilation, gas exchange, oxygenation.

- Enhances toxin elimination and brain oxygenation - better problem solving, stability.

- Prevents pooling of secretions, reduces infection risk.

- Helps in management of COPD (walking, cycling, strength training).

- Yoga breathing aids asthma control.

4. Gastrointestinal System

- Improves appetite, GI tone, and peristalsis.

- Relieves constipation (rowing, swimming, walking, sit-ups).

- Helps in IBS and digestive disorders.

5. Metabolic/Endocrine System

- Increases metabolic rate (up to 20x during strenuous exercise).

- Continued increased metabolism after activity.

- Uses triglycerides and fatty acids - decreases cholesterol, triglycerides, HbA1C.

- Promotes weight loss and insulin sensitivity.

6. Urinary System

- increased blood flow - better waste excretion.

- Prevents urinary stasis, reducing UTI risk.

7. Immune System

- Exercise aids lymphatic circulation - improved pathogen destruction.

- Moderate exercise enhances immunity.

- Excessive strenuous exercise may temporarily Decreased immunity - need rest for recovery.

8. Psychoneurologic System

- Depression/stress can reduce activity - slumped posture, fatigue.

- Regular exercise:

- improves mood, decreases anxiety and stress.

- increases neurotransmitters (serotonin, norepinephrine), increases endorphins.

- Improves sleep quality.

- Excessive exercise sometimes linked to eating disorders.

9. Cognitive Function

- Improves decision-making, problem solving, planning, attention.

- Strengthens neuronal connections.

- Cross-lateral movements (e.g., Brain Gym) aid ADD/ADHD, learning, mood disorders.

10. Spiritual Health

- Yoga and meditative movement - improve mind–body–spirit balance.

- Promote relaxation response (RR) - decrease HR, BP, RR, stress.

- Techniques:

- Progressive muscle relaxation.

- Labyrinth walking or finger-tracing mandalas - induce calm, reduce insomnia.

3.3 EFFECTS OF IMMOBILITY

Immobility negatively impacts multiple body systems. The severity depends on duration of inactivity, health status, and sensory awareness. Early ambulation is key to preventing complications.

1. Musculoskeletal System

- Disuse osteoporosis - bone demineralization (risk of fractures).

- Disuse atrophy - muscle wasting, Decreased strength and function.

- Contractures - permanent muscle shortening, deformities (foot drop, wrist drop, hip rotation).

- Joint stiffness/pain - immobility of collagen tissue and calcium deposits in joints.

2. Cardiovascular System

- Diminished cardiac reserve - tachycardia with minimal exertion.

- Valsalva maneuver (breath-holding during straining) - Decreased venous return, possible arrhythmias.

- Orthostatic hypotension - dizziness, fainting, Increased HR on standing due to poor vasoconstriction reflex.

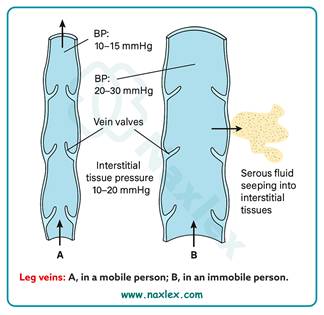

- Venous vasodilation/stasis - pooling of blood in legs, incompetent valves.

- Dependent edema - fluid accumulation in sacrum, heels, legs.

- Thrombus formation – DVT (deep venous thrombosis) risk, possible embolism (lungs, heart, brain).

3. Respiratory System

- Decreased lung expansion - shallow breathing, Decreased vital capacity.

- Pooling of secretions - risk of respiratory acidosis, infection.

- Atelectasis - collapse of alveoli from mucus blockages and Decreased surfactant.

- Hypostatic pneumonia - pooled secretions promote bacterial growth, serious infection risk.

4. Metabolic System

- Decreased Metabolic rate - reduced energy needs.

- Negative nitrogen balance - protein breakdown > synthesis, poor wound healing.

- Anorexia - decreased appetite, risk of malnutrition.

- Negative calcium balance - bone calcium loss due to lack of weight-bearing.

5. Urinary System

- Urinary stasis - incomplete emptying in supine position.

- Renal calculi - excess calcium in urine forms stones.

- Urinary retention - bladder distention, overflow incontinence.

- Urinary infections (UTIs) - stagnant urine supports bacterial growth, reflux may infect kidneys.

6. Gastrointestinal System

- Constipation/impaction - Decreased peristalsis, weak abdominal muscles, uncomfortable bedpan use.

- Straining (Valsalva) - Increased intra-abdominal pressure, risk to cardiovascular system.

7. Integumentary System

- Reduced skin turgor - skin atrophy, loss of elasticity.